The Ice Balloon: S. A. Andree and the Heroic Age of Arctic Exploration (17 page)

Read The Ice Balloon: S. A. Andree and the Heroic Age of Arctic Exploration Online

Authors: Alec Wilkinson

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Travel, #Adventure, #Biography, #History

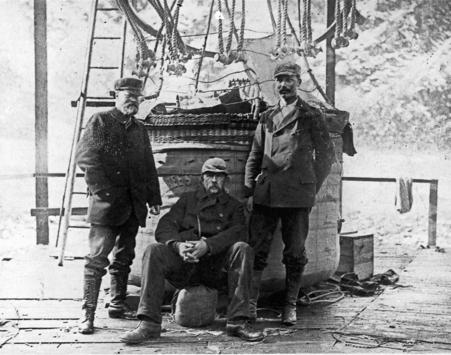

Carpenters raised the balloon house, while others among the crew placed the guide ropes in asphalt tubs filled with petroleum jelly and tallow and let them soak for fifteen hours. They ran the ropes through their hands to strip off the excess coating; mostly this was done by Strindberg and Eckholm. Then they attached the ropes and the drag lines to the stern of the steam launch and pulled them through the harbor to determine the effect of their weight. They also filled a small balloon made from goldbeater’s skin—the outer membrane of a calf’s intestine, which is used in making gold leaf—and let it go, but it rose straight above them, into the clouds, so that they couldn’t tell how it had behaved or even what direction it had taken. One evening Andrée and the others practiced splicing lines and tying knots “so we won’t be too clumsy in such things.” To a friend he wrote, “No problems are weighing on our minds.” All that remained was to “travel to the Pole. Nobody on board appears to have got the idea that this will meet with any difficulties.” Andrée was pleased at superintending all the work. “It is great to hypnotize on a large scale,” he wrote.

On July 11, after Andrée completed his watch aboard the

Virgo

at two in the morning, he went ashore and climbed into the basket, which had been hung so that it could sway in the wind. He had brought with him a copy of Nordenskiöld’s book,

Journey of the Vega

, which he read a few pages of and then placed “on the book-shelf which had newly been set up. In this way I consecrated, as well as I could, the new vessel.”

By the third week of July the balloon house was finished. Heavy felt covered the floor and the walls; the roof was made from cloth, and the windows from gelatin. The balloon was unpacked and examined for tears, and then it was laid out. The following day it snowed, and the day after that the balloon was inflated. All of Europe and much of America were following Andrée’s mission, and steamers and schooners carrying reporters and tourists began arriving. Almost daily, for two hours in the morning and two in the afternoon, Andrée gave lectures for them, which he enjoyed. Dispatches were sent to the wider world. A paper in Philadelphia wrote that “the daring of the aeronauts and the extremely novel enterprise in which they risk their lives give to Andrée’s departure something of the interest which attended the sailing of Columbus’s ships upon their immortal voyage. It is impossible, however, to suggest historical parallels to his curious journey.”

The balloon had been filled for three days, when Eckholm said there was a strong odor of hydrogen in the house, and that gas had caused the balloon’s cover to rise and flutter in the wind. Beneath the cover they found leaks they varnished. Andrée wrote a friend that as soon as the cover was restored, it would be time to leave. “After that, I and others must accept what the forces of nature choose to do. We shall, of course, use all our strength to the end, but this, despite all is only a drop in the ocean, once the balloon has been released.”

They needed a southerly wind, but the wind blew mainly from the north or northwest, mostly weakly, and sometimes hardly at all. The

Virgo

was insured until August 20. To reach Sweden by then, it would have to be loaded by the fourteenth.

That morning a ship with three masts anchored about a mile offshore. As it swung on its line Strindberg wrote, “it showed itself in clear profile.” He and Andrée and Eckholm were taken toward it in a launch. “We used the binoculars until our eyes began to hurt,” Strindberg went on. They thought they knew who it was, “But we did not yet dare to believe it,” he wrote. “As we came to 500 meter’s distance the name began to appear and I was the first to confirm that it was Fram! It was like a dream. What a strange coincidence, what a peculiar twist of fate!”

They waved their hats and gave four cheers. Andrée made no note of the occasion, but it is not unreasonable to assume that as he approached the ship he was uneasy. If it turned out that the

Fram

had reached the pole, his own voyage would be superfluous. On the other hand, if the

Fram

hadn’t made it, he might prove that three years of effort could be bettered in a week. At the gangway ladder, according to Strindberg, Lieutenant Hansen told them something that Andrée couldn’t have foreseen—“the sorrowful news regarding the fate of Nansen and Johansen”—that they had left the ship for the pole and not been heard from. (“Yet hope still remains,” Strindberg wrote.) From Captain Sverdrup, Andrée heard that the

Fram

had not traveled the course it had hoped to; it had zigged and zagged with the pack, heading mainly west, and never very far north, and been released above Spitsbergen. Nevertheless, Nansen might still return having reached the pole.

The

Fram

left the following day, and a few days later, in Tromsø, met up with Nansen and Johansen, who had been traveling on Jackson’s boat. Meanwhile, Andrée wrote, “Today we sharpened the scissors, with which the balloon will be cut apart.”

On August 16, Andrée sent a telegram announcing that the expedition was returning, having not gotten a favorable wind. The next day at ten in the morning the balloon valves were opened, and by five it had been deflated. “Like a rag the proud airship sank to the floor,” Andrée wrote. The correspondent for

Aftonbladet

described the mood on the island as “quite depressed.” The hydrogen plant was dismantled, and its parts were stored by Pike’s cottage, and the walls of the balloon house were taken down and stored on the beach. Andrée thought that forty people could put the house back up in three or four days, compared with the thirty-five days it had taken to build it. More days could then be devoted to waiting for the wind.

Nowhere does Andrée write that he was affected by Nansen’s return, but his feelings toward him were apparent when he concluded his speech in London in 1895 by saying, “Is it not more probable that the north pole will be reached by balloon than by sledges drawn by dogs, or by a vessel that travels like a boulder frozen into the ice?” The sentiment, however—provoked by nationalism—that Nansen had won by traveling farther north than anyone else, and Andrée been defeated, was circulating. The Norwegian novelist Alexander Kielland wrote that Nansen’s return “was a blessing for the entire country,” Sweden’s rival. “Even the Swedes had to contribute to the splendor with their 3 wind bags who returned home with the balloon between their legs.”

Andrée’s plan had relied on ships and sledges having failed, but Nansen had shown that each could at least still come close. What was needed, some said, was not a balloon but an icebreaker. In addition Nansen’s intrepidness cast a shadow of hesitancy, even cowardice, over Andrée’s return. Furthermore, some people asked what Andrée, in a sprint, might learn that Nansen on a long tour hadn’t. One observer wrote of Andrée’s changed circumstances, “Instead of the original jubilant expectations, he is now surrounded by mistrust and indifference on many sides.”

By the end of August, Andrée was back in the patent office. While the world had Nansen lead parades and gave him honors, Andrée sat at his desk. A reporter walking down the street in Stockholm with him in September was surprised at how few people noticed him. “It is strange to see how little known this man was amongst his own townspeople, there was not a hat that was lifted for his sake, nobody who passed turned around and whispered, ‘This was Andrée who walked here.’ ”

Over the winter Nansen and Andrée exchanged letters. Nansen felt that Andrée’s voyage was dangerous, and he hoped, perhaps from self-interest, that he wouldn’t try again. “I believe Macbeth’s golden words could be placed on your banner,” Nansen wrote. “ ‘I dare to do all that may become a man; Who dares do more is none.’ It is in drawing this boundary that true spiritual strength reveals itself.” Andrée wrote back, “Since I have proven that I am capable of returning, I am greatly tempted to do just the opposite.”

Andrée’s backers were still eager to help him. Baron Oscar Dickson who had also supported Nordenskjiöld wrote, “Please bear in mind that those of us who have contributed to the expenses for this year, have a preferred right to subscribe to the next try.” Alfred Nobel offered to pay for another balloon, but Andrée said that he didn’t think that a better balloon could be designed or built. “The balloon is, with regard to its construction and fabrication, as far as I understand, as good as it could be made,” he wrote Nobel. To another friend he wrote that all care had been taken to prepare the balloon. “All that is humanly possible has been done when it comes to sealing,” he wrote, “the best-known method for the seams has been used, and the most renowned manufacturer employed, what is left?” Because the balloon had been heavier than he had expected, though, he had a band three feet tall added to its equator so that afterward the balloon was a hundred feet tall and sixty-seven and a half feet across at its widest point. The first version had been spherical, and the new one was slightly elliptical.

Andrée had been home from Dane’s Island only a little longer than a month when his difficulties deepened. In a speech to the Society of Physics, Eckholm revised several of his predictions about the balloon and the trip. Friction from the drag ropes would cause the balloon to travel half as fast as Andrée had forecast, Eckholm said, meaning the trip would take twice as long. Andrée had allowed a margin of safety that was five times greater than the time he thought necessary—that is, for the six-day trip that he had assumed, he had designed a balloon that he believed could stay in the air for thirty days. Now that the trip, according to Eckholm, would take twelve days, the balloon had to remain aloft for sixty days, which almost everyone doubted it could. On Spitsbergen, according to measurements Eckholm had made, it lost gas at a rate that suggested seventeen days was more reasonable. Eckholm’s measurements had been difficult to interpret, however. The balloon seemed to lose gas erratically, which didn’t seem probable. Not until he was back in Sweden did he learn that Andrée had been having the balloon refilled.

Eckholm also told his audience that his calculations had predicted a straight path for the balloon, but now he thought that it would travel “in many crooks,” which would double and perhaps triple the miles needed to reach land on the far side of the pole. Furthermore clouds would force the balloon to travel close to the ground and slowly, and sometimes even to stand still.

Andrée had been content to arrive at the pole in the air and return over the ice if he had to, but Eckholm felt that such a trip was beyond even Nansen’s capabilities, and probably out of the reach of an engineer, a meteorologist, and a physicist who had no experience of traveling in the Arctic and hadn’t trained for it, either. He wanted the balloon somehow made able to travel faster or the envelope made less permeable, which was not simple, considering that in applying nine miles of thread, needles had passed through its surface something like eight million times.

Andrée defended himself by saying that he thought that the balloon would not lose gas as quickly as Eckholm predicted, and that as time passed it would lose less. Moreover, once enough gas had been lost, one of the guide ropes could be discarded, with the result that the balloon would be lighter and go faster. Furthermore, even seventeen days was more than sufficient for their purposes. Strindberg added that the polar ice would cause less resistance to the ropes than snow, and that if a strong wind blew at the start they would cover more ground than forecast and so spend less time in the air.

Eckholm didn’t merely give a speech, he also went to the Stockholm train station to meet the king’s train and tried to persuade him to withdraw his support. When the king, surprised to see him, asked where Andrée was, Eckholm disingenuously said that he had expected him to be present, and that he must have been delayed, meaning to imply that he was acting with Andrée’s approval. Eckholm also wrote to some of Andrée’s backers, hoping to convince them that Andrée’s flight was impossible.

On September 19, Strindberg wrote his brother Sven, “Next year’s expedition is likely to involve a great change. Eckholm is probably not coming along! This is still being kept secret. This is the situation. Eckholm, upon return, has blamed Andrée for failing to keep his promises regarding the balloon’s permeability and poses preconditions for his participation, by which Andrée neither can nor wishes to abide as they show a mistrust of Andrée’s integrity. Moreover, he has behaved in a tactless manner in several ways, partly by waiting alone with tail wagging to receive the king as he returned from Norway, partly by secretly going against agreement and writing to the expedition’s patrons in an attempt to depict it as dangerous. Judging by appearances it seems as though he is suffering from pressures from his wife’s side and now wants to emerge from the situation with dignity intact. All of this is between us!”

Scholars have speculated that Eckholm was trying to preserve his reputation. If Andrée discovered the pole without him, Eckholm would look like a turncoat and a coward. If the trip were abandoned for practical and technical reasons, though, he might appear to be a rational man of science who had the courage to put the well-being of others above his own ambitions and whose caution had saved lives.