The Hurlyburly's Husband (14 page)

Read The Hurlyburly's Husband Online

Authors: Jean Teulé

The King came out. Montespan knew the King was short but was surprised by quite how short. He was tiny and tried to compensate for it by holding himself stiffly. He wore high-heeled shoes and had a thin moustache. Beyond that, Louis-Henri could not make out his features, for Louis XIV had stopped in front of a window with his back to the sun. After a short silence the radiant figure of the monarch, silhouetted against the light, with his ministers scurrying around him, enquired of the Gascon, ‘Why are you all in black, Monsieur?’

While etiquette required one to remove one’s hat in the presence of His Majesty, Louis-Henri now placed the grey hat on his head – a colour the King hated – and replied, ‘Sire, I am in mourning for my love.’

‘In mourning for your love?’

‘Yes, Sire, my love has died. Killed by a rogue.’

At a time of universal and abject servility, anyone who dared to raise their heads above the fawning crowd had to be peculiarly hot-blooded and uncommonly determined.

The distinguished figures at the far end of the reception hall were frozen with terror at the marquis’s behaviour. The hot-headed Gascon had overstepped all bounds. Louis XIV would not tolerate this direct insult – a crime of

lèse-majesté

.

The marquis, having said his piece, bowed arrogantly and, in full view of the courtiers, broke his sword before the tyrant to show that he would no longer serve him, for he was a man who loved too much. Then he very casually turned his back on the King. The sound of his heels faded away across the waxed parquet floor and he returned to his carriage.

Such behaviour was unthinkable. No one had ever committed such an offence in His Majesty’s presence. Everything – fire, water, night, day – was subject to the will of this living god, whose face was faintly pitted by smallpox. The King said nothing, and the silence spoke volubly of the crime committed. Then he spluttered with laughter. ‘And so? I am fucking his wife! What more could I do for him?’

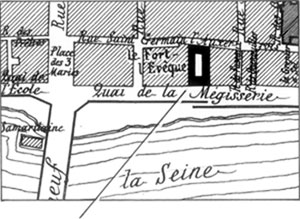

Everyone around him laughed; of course they had to agree. The horned carriage had not gone far before the King’s henchmen caught up with it. Lauzun was at their head and he rode up alongside the marquis’s door in a swirl of dust and shouted, at a gallop, ‘Let your coachman go on and drive the berlin to Rue Taranne, but he will have to stop first to leave you outside Fort-l’Évêque.’

‘The prison in the Vallée de la Misère?’

‘I have a

Zettre de cachet

which authorises the King to imprison whomsoever displeases him for an indeterminate period and without trial!’

‘The King did give me horns! Take heart, my soul

And admire thy bliss

Presently thou shalt go – be praised, oh wife –

To the highest point of honour!’

In the cramped, insalubrious prison on Quai de la Mégisserie – nicknamed the Vallée de la Misère because of the great number of animals that were put to death there – Montespan, with blood on his nails, languished behind a door locked by the most secure of padlocks. Through a high basement window, a ray of light entered the dry well that served as a dungeon at Fort-l’Évêque, and left a little dusty patch of brightness on the earthen floor. The isolation could not appease his torment. While the animals being slaughtered outside screamed with pain, the marquis in fetters sang at the top of his voice the last couplets telling the good folk of their King’s loves:

‘To be a king’s cuckold, ’tis untold honour,

A plague on it, I know it well!

Black sorrow is most blameworthy

How dare I flee my own good fortune?’

‘Shut up in there! You’re singing off-key! … I’d rather listen to the sound of those beasts having their throats cut! I have a musical ear, I do!’

Louis-Henri turned this way and that inside his pitch-dark cell.

‘Is someone there?’

A voice replied in the obscurity, ‘Aye, there is, someone they’ve thrown in this prison, but what for? I’m not a libertine writer, nor a shameless hussy, nor an indebted gamester. I’m not mad enough to have committed a crime of

lèse-majesté

. So what am I doing in Fort-l’Évêque, the prison for the King’s arrests? And if now, in addition, a fellow inmate who is such a poor singer is inflicted upon me…’

Silence reigned in the dungeon, then Louis-Henri, in chains and on his knees, dragged himself across the mouldy straw to the faint ray of light. In the darkness he looked for his fellow prisoner. ‘Where are you?’

The other voice continued, ‘’Tis true, indeed! I am naught but a maternity doctor, doing my job, so why have I landed here? It was the end of the afternoon. I was alone in my house on Rue Saint-Antoine. I was about to have supper when there came a knock at the door. I opened it. Hiding on either side were two soldiers (I could hear the clicking of their weapons against the buttons of their uniform) and they grabbed me by the arms. A third man arrived from behind and bound my eyes and ordered, “Not a sound or I’ll cut your throat! Monsieur Clément, bring your instrument case.” Forsooth! I thought, I have nothing to fear. Am I not used to these mysterious little expeditions to the homes of people of rank at a time when my young clients often come into the world as best they can? I was made to climb into a coach from court (I noted the delicate creaking of the oiled hubs as used at Versailles) and, after we had ridden for a while, I was left at the foot of a stairway, which I climbed, guided by a nurse (she had a millet-seed rattle bumping against her chest). And I went into a bedroom on the first floor of a discreet dwelling set back from Rue de l’Échelle.’

‘How did you know the address if you were blindfolded?’

‘My ears were not bound …’

Chains dragged along the floor and the face of Clément, the maternity doctor, appeared in the faint ray of light.

‘Just nearby, I recognised the unbearable ring of the cracked bell at the Chapelle Sainte-Agonie. I had gone there one morning to assist a birth (miraculous, surely) and I had complained to the sisters, “You’ll have to change that bell with that off-key knell to it, else I’ll not come back to this hellish racket to bring any more little baby Jesuses into the world!” And I also knew it was set back from the street because downstairs I could hear the hammering of a wooden heel-maker. He uses wood that is too freshly cut. I bought some heels from him once and very soon they split. And I knew from the hammering that it was this wood that wasn’t dry enough that he was hitting. You can tell things like that from the tonality …’ he continued, clicking his fingers next to his ear and dislodging his dusty wig, which gave off a cloud of powder.

Louis-Henri coughed in the ray of light and withdrew his head. The doctor Clément left his head in the light: he was a sweaty red-faced man of fifty-odd years, with a drunkard’s puffy nose. Montespan listened.

‘As I went alone into the bedroom, still blindfolded, I exclaimed, “Ah, ah, it seems I am to fetch an infant from where it is by groping up the very same way that got it there.” In her bed, undergoing her first labour pains, there was a particularly well-made young woman whom I could feel with my fingertips – a human statue of the sort you see only in the grounds of a chateau, a woman made for a lord from Mount Olympus. Standing next to her, nervous and worried, was a little man (his voice came, rather, from below). I asked him whether I was in a house of God, where one is not allowed to drink or eat; as for myself, I was famished, having left my home just as I was about to sup. The little man complied readily. He handed me a pot of jam and some bread. “Have as much as you like, there is more.” “I believe you,” said I, “but is the wine cellar less abundant? You have not given me any wine and I’m stifling.” The little man became annoyed: “A bit of patience, I cannot be everywhere at once.” “Ah, well done,” I said, when I received a goblet filled to the brim. This gentleman was likely not a bourgeois – too many sounds of extravagant rings on his fingers clinking against the glass, and in the manner he handed the wine to me I understood that he was not at all in the habit of serving …’

The practitioner withdrew his head into the darkness. Louis-Henri, more and more interested in his cellmate’s story, moved into the faint ray of light. ‘Go on.’

Clément resumed his tale.

‘When I had drunk, the man asked me, “Is that everything?” “Not yet,” I replied. “A second glass to drink with you to the health of the good woman!” As the man said no, I told him with a smile that the woman would not give birth so easily and, if he wished the child to be handsome and strong, he must drink to its health. And so, for the love of his progeny, he toasted with me. Just then a piercing cry signalled the infant’s first attempt to enter the world. The child was in the breech position, but came out easily. I touched his little feet to make certain everything was all right, slid my hands up his little legs – ’twas a boy – and tied off the cord. I placed my palms on his chest, where his heart was beating very rapidly, and went on up to his frail neck, and it was then that the little man with lots of rings stopped my wrist and called out, “Lauzun!” The hinges on the door leading to the landing creaked. There came a squeaking of leather boots, no doubt this Lauzun fellow. I also heard the millet seeds bouncing in the nurse’s rattle and the little man’s voice ordered her, “You, only you, must stay secretly by this child who shall have no name.” “As it pleases you,” replied the maid. “I will not go out, save to pray at the neighbouring chapel at the eleven o’clock mass.” Then, heavier by a pouch, I merrily set off to be taken back to my home, or so I thought, but I was brought here, to Fort-l’Évêque (which I recognised from the cries of the animals being slaughtered without). And since that moment I have been waiting – what for? Who for? You?’

Montespan withdrew into the darkness. He thought for a moment, then asked, ‘When a married woman gives birth, is her husband always held to be the father?’

‘Oh, yes,’ replied the practitioner. ‘And that is so whosoever the genitor might be. The husband remains legally the father according to the fundamental principle of Roman law

Is pater quem nuptiae demontrant!’

‘Thus, the husband may enjoy all rights to the child?’

‘But of course.’

Silence fell again in the cell, then Montespan sang, lungs fit to burst,

‘Bourbon so loved my wife,

With child he left her, so

To the fleur-de-lis long life!’

‘Marquis, your turn has come to leave the dungeon! Yesterday, the doctor was set free. Today, you will be released. Mind the daylight! The sun will burn your eyes.’

The gaoler’s torch, which was steeped in foul-smelling oil, smoked and flickered as he raised his arm towards the corridor, inviting the inconvenient husband to follow the light. Rats ran across the damp flagstones, their claws scraping against the stone, and the warder pushed Montespan out into the Vallée de la Misère.

Quai de la Mégisserie was dazzling in the sunlight and Louis-Henri, still in chains, raised his forearm to his eyes to protect them from the glare. While he was being unshackled, his pupils gradually adapted and through his sleeves he began to see the vivid colours of the

quai

, bustling with people and sedan chairs weaving among mountains of slain cattle. The marquis heard a drum roll. Soldiers moved apart and formed a circle around him. Nauseating steam rose from huge boilers. Sweating women plunged chickens into the swirling water to scald them before plucking them, and then, curious, they went over to the guard of honour the soldiers had formed. Burghers, yokels and a few noblemen clustered round. The drum stopped beating and a horseman of the watch moved into the circle facing Louis-Henri.

At nine o’clock in the morning on 7 October 1668, the horseman read the royal command, proclaiming in a thundering voice, “‘By order of His Majesty the King!”’

Everyone fell silent. Even the mortally wounded beasts at the butchers’ now died soundlessly on the shores of the river. Looking up at the sky, they watched as seagulls circled overhead, coming up the Seine from the sea. The web-footed scavengers swooped and seized bovine guts and hens’ intestines from the water and carried them skyward like streamers of dancing red, green and blue; it gave a festive touch to the blue sky. As the gulls dipped towards the surface of the yellow river stippled with points of light, the Gascon followed the beating of their wings. The river Seine in the sunlight was like Françoise’s blond hair; how he had loved to plunge his long fingers there, like the teeth of a comb. He sighed, whilst the horseman of the Paris watch again raised his voice: “‘His Majesty, being most dissatisfied with the noble Marquis de Montespan…”’

‘What? He is dissatisfied with me? Oh, the scurvy knave!’

The horseman pretended not to have heard, or to have heard another word, such as brave … grave … and continued, ‘“… orders the horseman of the watch of the City of Paris forthwith, and by virtue of this order of His Majesty, that once said noble sir and marquis has been set free from the prison of Fort-l’Évêque where he was detained, he shall in the name of His Majesty be ordered to leave Paris within twenty-four hours and repair to his estate located in Guyenne, there to remain until further notice ...”’