The Hunt for the Golden Mole (15 page)

Read The Hunt for the Golden Mole Online

Authors: Richard Girling

Information was just the starting point. On its own it might help conservationists define their objectives but it didn't provide the means of carrying them out. If saving the giant panda or black rhinoceros was to be more than just a pious hope, then some means of raising money would have to be found. Once again all eyes were on Huxley. Having been instrumental in

driving forward the information network, he was now the catalyst for effective action. It is a long story to which my brief account will do scant justice, but the response to Huxley's

Observer

articles was electrifying. Many others would be centrally involved â most importantly the director-general of Britain's Nature Conservancy, Max Nicholson â but it was Huxley who inspired the foundation of what is now the world's biggest non-governmental conservation organisation, WWF (originally the World Wildlife Fund, and since 1986 the Worldwide Fund for Nature). Its official launch was at the Royal Society of Arts in London on 28 September 1961, when the speakers included Peter Scott and Huxley himself. Scott became WWF's energetic first vice-president, and recruited Prince Bernhard of the Netherlands and the Duke of Edinburgh as its international and UK presidents. He also designed the WWF's famous panda logo.

Progress was rarely smooth. Conflicts with other conservation bodies, especially those in America, were par for the political course. Fairfield Osborn, who by now had founded America's Conservation Foundation, was initially a board member of WWF-US, but resigned and refused to be a trustee. (The Conservation Foundation would not merge with WWF until the 1980s, and even then WWF-US, along with Canada, would not accept the name change adopted by every other country.) Elsewhere, the royal figureheads' penchant for hunting would cause controversy reminiscent of the âpenitent butchers'. So, later, would sponsorship from oil and agro-chemical companies. There were spats with the IUCN (with which for many years it shared an office) and with the Fauna Preservation Society (over who should take the credit for saving the Arabian oryx). But gradually, over the years, like magnetised particles the forces of conservation would turn and point in the same direction.

It is a coincidence that my own idealised and wildly optimistic notion of African wildlife should have developed during that early, critical post-war period. Coincidence, too, of a happier sort, that a couple of decades later I should find myself sitting alongside my boyhood heroes, Attenborough and Scott, on the judging panel of an environmental essay competition run by

The Sunday Times

in memory of the nature writer and broadcaster Kenneth Allsop. I knew little of Julian Huxley then (and had certainly never read his

Observer

articles, which were published while I was still at school), and would never see or hear him speak â he died, aged eighty-seven, in 1975 â but his voice and philosophy, however unconsciously, were fundamental to every entry we received. It is only now that I realise the centrality of his thinking to everything I believe about wildlife. How else, I wonder, would I see any point in searching for the world's most improbable mole?

A

man at a party, name of Chris, has heard I am writing a book and wants to know what it's about. I tell him it's about an owl pellet. He laughs at what he takes to be a joke, and wishes me luck with my ânovel'. Sometimes it does feel like that. Men like Roualeyn Gordon-Cumming, Abraham Dee Bartlett, Frank Buckland, Carl Hagenbeck and Frank Buck could so easily have stepped from the pages of fiction. I am surprised, too, by the elusiveness of facts, and fall into the layman's errors of expecting simple answers to simple questions, of failing to understand the thinness of the membrane between fact and fantasy. The evidence for the Somali golden mole would hardly fill a teaspoon. Even if I do find it, I will have to rely on others to âread' it for me. But then of course it was the very uncertainty of its existence that caught my imagination in the first place. If I wanted to be certain of success I would have searched for a baboon.

In

Chapter One

I mentioned some research from the University of Queensland, published in 2010, which argued that a third of all mammals previously thought extinct were actually still alive. The story flickered briefly across the news pages and then fluttered into the archive, leaving nothing behind but unanswered questions. If so many species are returning from the

dead, then why are we being warned of a looming mass extinction, the worst since the dinosaurs? And how can we be sure that a species has completely died out, leaving not a single individual anywhere in the world? In some cases, it seemed to me, when the only evidence was an owl pellet, there was reason to doubt that they had ever existed in the first place. It was like a door opening on to a maze with an enigma in the middle and a riddle at each corner.

At this time I had little idea of what I was getting into. I knew only that the endless churn of species â discoveries, rediscoveries, extinctions â was something I would like to write about. Working on a piece for

The Sunday Times Magazine

, I asked the curator of mammals at the Natural History Museum, Paula Jenkins, if I could be shown specimens of some of the so-called âLazarus species' stored in her collection. Thomas Henry Huxley would tap-dance through the Central Hall if he could see how completely his vision for the museum has displaced Richard Owen's worshipful celebration of the Old Testament. The exhibition space is just the smile on the museum's face. The soul, brain and guts of the place are in the huge scientific body that stretches out behind it. Trolley squeaking like a tumbrel, Paula Jenkins leads me through endless back corridors, past numberless cabinets crammed with skulls, skins and skeletons. There is a vaguely hospital-like smell which intensifies as she opens a drawer and, from among the family

Cheirogaleidae

, lifts out the body of a tiny animal. It lies on the trolley with its arms pinned tightly to its sides as if it died while standing to attention. Like all museum specimens, it is gutless, boneless and scented with insecticide. Like many others in this faunal mausoleum, it is the holotype, the original collected item from which the species was first described. When Paula Jenkins turns it to the light, its babyish face wears an expression of pained astonishment. This is the

hairy-eared dwarf lemur,

Allocebus trichotis,

which has lain in its drawer ever since a man named Crossley shot it in north-east Madagascar in 1875. Paula has worked at the museum for forty years but can't remember anyone else ever wanting to see it.

According to the late American naturalist Francis Harper, not a single living example of

Allocebus trichotis

was seen between 1875 and 1945, when Harper himself declared it extinct. This was not an arbitrary personal opinion but the straightforward application of a widely accepted scientific principle. It stood to reason, it was a

fact

, that any creature not seen for fifty years must have disappeared for ever. That was how extinction was defined. Goodbye, dodo. Goodbye,

Allocebus trichotis

. End of story. Then in 1967 came the miracle. A researcher in Madagascar reached into a hole in a tree and out came the hairy-eared dwarf lemur. It would prove, however, to be the very briefest of resurrections. Darkness closed again, and there was not another âofficial' sighting until 1989, when WWF found it near the Mananara River. Crucially this time they took the trouble to interview the locals, to whom

Allocebus trichotis

was anything but a mystery. The bare facts of its existence were as follows:

It was a very small animal â head and body typically between 125 and 145 millimetres, tail between 150 and 195 millimetres, weight between 75 and 98 grams. It was nocturnal and nested in forest trees, usually between three and five metres above the ground. Throughout the cold season, May to mid-October, it hibernated deep inside tree holes. All this, of course, helped to explain its supposed âextinction' and to prove the inadequacy of the fifty-year rule. If you wanted to see

Allocebus trichotis

, then you would have to go and look for it. It wasn't going to scuttle out of the forest and say, âHi, I'm not extinct.' Even the Madagascans saw it only between October and March, which is the tree-cutting season in the annual cycle of slash-and-burn.

The next specimen on Paula Jenkins's trolley is something that looks like an inflated shrew. Unusually, it is stuffed and mounted as if for public display â a vulgar, unscientific practice abandoned by the museum in the late nineteenth century (this one was collected in 1898). The Cuban solenodon,

Solenodon cubanus

, is from the outer fringes of the mammalian estate, where weirdness lies. It is a genuine primitive, similar in many ways to the early mammals that followed the dinosaurs. The long bendy snout looks frankly comical â a clown's proboscis â though the naked, rat-like tail is less endearing. Less attractive still are its fangs, through which it can inject venom like a snake. You wouldn't find Michaela Denis cuddling one of these, but then she almost certainly never saw one. By 1970, after none had been seen since 1890, the Cuban solenodon was officially declared extinct. It remained non-existent for just four years before confounding its obituary and reappearing in Cuba's Oriente Province. Having no faith in apparitions or ghosts, science had to admit its error.

Solenodon cubanus

might be endangered, but it was definitely not extinct.

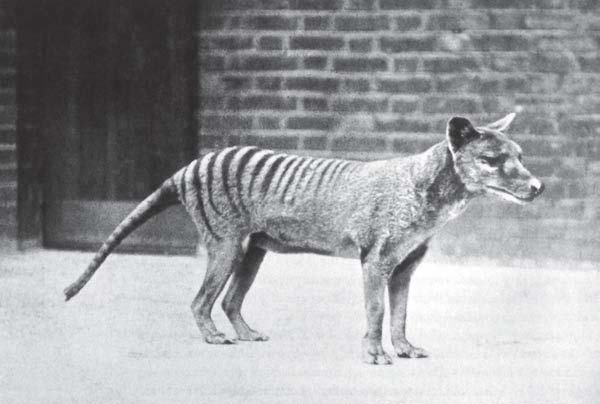

The Natural History Museum has many other examples. Jentink's duiker, whose skull is next on the trolley, was not seen alive between 1889 and 1948. The Cyprus spiny mouse had been lost for twenty-seven years before it popped up again in 2007. Fea's muntjac went missing between 1914 and 1977. The thylacine has not been seen in the wild since 1933, though there are plenty of amateur enthusiasts in its native Tasmania (by no means all of them obvious hoaxers or wishful romantics) who are prepared to say otherwise. Reported sightings, including photographs and at least one video clip, comfortably outnumber glimpses of the Loch Ness Monster. More than all the other specimens I see on this visit, the two stiffened pelts Paula Jenkins now lays on the tumbrel bear a colossal weight of tragedy. The thylacine, popularly known

as the Tasmanian tiger, was a gloriously improbable assemblage of unmatched parts whose scientific name

Thylacinus cynocephalus

(âdog-headed pouched one') precisely describes its uniqueness. It was a carnivorous, dog-like marsupial with exceptionally wide-opening, bone-crunching jaws and a conspicuously striped rump. It was likely to have been near-extinct on the Australian mainland even when the museum's two specimens were collected in 1839 and 1865, but it managed to cling on in Tasmania. Even there, however, its taste for sheep made it anathema to farmers, who shot it on sight, and it would have taken a determined conservation effort to save it. Tragically, no such effort was made. The last scientifically validated individual was caught in 1933 and died in Hobart Zoo three years later. Since then â nothing. More than twenty-five scientific expeditions have done their best to confirm the amateur sightings, but all have ended in failure. The thylacine was declared extinct in 1982.

Next we head for the

bovidae

, the family of sheep, goats, cattle, antelopes and buffalo. Doubts about provenance are already raising questions about the very existence of some species â a line of thought that will lead directly to the golden mole, though it's antelopes that come to my attention first. I am still a stranger to the idea that entire species might be open to doubt; that the evidence for their existence might be too flimsy to pass forensic scrutiny. The red gazelle,

Eudorcas rufina

, for example, has never been seen alive. Its entire classification depends on three mysterious specimens bought at Algerian markets in the late nineteenth century. According to the IUCN, âmost authors' have accepted it as a genuine species, though âcontinuing doubt concerning the validity of this taxon' has persuaded it to change the classification from âExtinct' to the more enigmatic âData deficient'. None of the three specimens is in the Natural History Museum, but I have been expecting to see a similar rarity, the Arabian gazelle,

Gazella arabica

. Sadly there has been a crossing of wires. The evidence for

G. arabica

is even thinner than it is for

E. rufina

, and I am mistaken in my belief that I will find it in Kensington.

In fact, the only known example of the Arabian gazelle is a single male specimen in Berlin. It was apparently collected in 1825, when it was reported somewhat dubiously to have come from the Farasan Islands in the Red Sea. Some scientists have suggested that the

Red List

classification of âExtinct' should be changed, like the Red gazelle's, to âData deficient'. It is, they argue, illogical to classify as extinct a species which, in their opinion, never existed in the first place. Disappointingly I have muddled it with

Gazella bilkis

, which some authorities have classified as a subspecies of

G. arabica.

My mind whirls. A

subspecies

of a species that may never have existed? How am I supposed to make sense of that? Paula Jenkins tells me that the

museum's specimen is one of only five known to exist, all of which were collected in 1951 from Yemen â hence its English name, Yemen gazelle, or, more poetically, Queen of Sheba's gazelle. Arguments about its status now are literally academic. âThere is no doubt,' says the

Red List

, âthat the population originally described as

G. bilkis

is certainly now extinct, regardless of whether it was a species or a subspecies.'