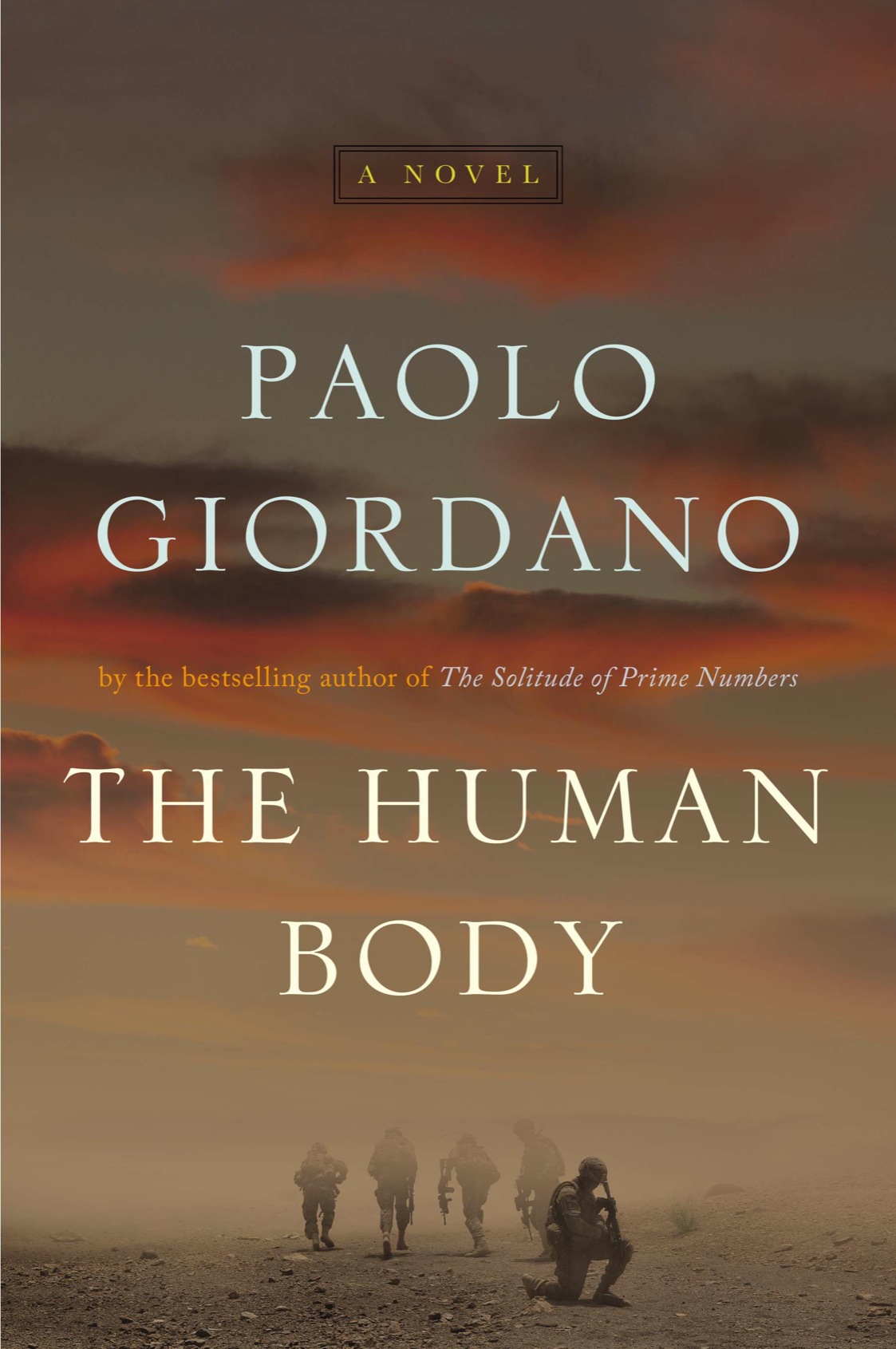

The Human Body

Authors: Paolo Giordano

ALSO BY PAOLO GIORDANO

The Solitude of Prime Numbers

VIKING

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

USA | Canada | UK | Ireland | Australia | New Zealand | India | South Africa | China

A Penguin Random House Company

First published by Viking Penguin, a member of Penguin Group (USA) LLC, 2014

A Pamela Dorman Book / Viking

Copyright © 2012 by Arnoldo Mondadori Editore S.p.A., Milano

Translation copyright © 2014 by Anne Milano Appel

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Originally published in Italian as

Il corpo umano

by Arnoldo Mondadori Editore S.p.A., Milano.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Giordano, Paolo, 1982â

[Corpo umano. English]

The human body / Paolo Giordano ; English translation by Anne Milano Appel.

pages cm

eBook ISBN 978-1-10163-169-0

1. Afghan War, 2001âFiction. 2. SoldiersâFiction. 3. ItaliansâAfghanistanâFiction. 4. War stories. I. Appel, Anne Milano, translator. II. Title.

PQ4907.I57C6713 2014

853'.92âdc 3 2014006927

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author's imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, businesses, companies, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Version_1

Part One: EXPERIENCES IN THE DESERT

Last Words from Salvatore Camporesi

To the tumultuous years at La Cascina

And even if these scenes from

our youth were given back to us

we would hardly know what to do.

âErich Maria Remarque,

All Quiet on the Western Front

A. W. Wheen, translator

EGITTO FAMILY

Lieutenant Alessandro Egitto, an orthopedic specialist assigned to the Alpine brigade

Marianna Egitto, his older sister

Ernesto Egitto, his father

Nini, his mother

OFFICERS OF THE SEVENTH ALPINE REGIMENT STATIONED IN BELLUNO

Colonel Giacomo Ballesio

Captain Filippo Masiero

THIRD PLATOON OF THE SIXTY-SIXTH COMPANY OF THE SEVENTH ALPINE REGIMENT (CHARLIE COMPANY)

Marshal Antonio René

Senior Corporal Major Francesco Cederna

Senior Corporal Major Salvatore Camporesi

Senior Corporal Major Arturo Simoncelli

Senior Corporal Major Michele Pecone

First Corporal Major Cesare Mattioli

First Corporal Major Angelo Torsu

Corporal Major Roberto Ietri

Corporal Major Giulia Zampieri, the only female in the platoon

Corporal Major Vincenzo Mitrano

Corporal Major Enrico Di Salvo

Corporal Major Passalacqua

Corporal Major Michelozzi

Corporal Major Rovere

DARI-ENGLISH INTERPRETER AT THE FOB

Abib

OTHER CHARACTERS

Irene Sammartino, Egitto's former girlfriend

Rosanna Vitale, one of René's clients

Flavia Magnasco, Salvatore Camporesi's wife

Gabriele Camporesi, Salvatore and Flavia's 4-year-old son

Agnese, Cederna's girlfriend

Tersicore89, Torsu's girlfriend

Dorothy Byrne, Marianna's piano teacher

Roberto Ietri's mother

Oxana, the masseuse at the base in Delaram

Colonel Matteo Caracciolo, commander of the Alpine brigade

Lieutenant Commander Finizio, military psychologist

I

n the years following the mission, each of the guys set out to make his life unrecognizable, until the memories of that other life, that earlier existence, were bathed in a false, artificial light and they themselves became convinced that none of what took place had actually happened, or at least not to them.

Lieutenant Egitto, like the others, has done his best to forget. He moved to another city, transferred to a new regiment, changed his beard length and his eating habits, redefined some old personal conflicts, and learned to ignore others that didn't concern himâa difference he had by no means been aware of before. He's not sure whether the transformation is following some plan or is the result of an unsystematic process, nor does he care. The main thing for him, from the beginning, has been to dig a trench between past and present: a safe haven that not even memory would be able to breach.

And yet, missing from the list of things he's managed to rid himself of is the one thing that most vividly takes him back to the days spent in the valley: thirteen months after the conclusion of the mission, Egitto is still wearing his officer's uniform. The two embroidered stars are displayed at the center of his chest, in precise correspondence to the heart. Several times the lieutenant has toyed with the idea of retreating to the ranks of civilians, but the military uniform has adhered to every inch of his body, sweat has discolored the fabric's pattern and tinted the skin beneath. He's sure that if he were to take it off now, the epidermis would peel away as well and he, who feels uncomfortable even when simply naked, would find himself more exposed than he could stand. Besides, what good would it do? A soldier will never cease being a soldier. At age thirty-one, the lieutenant has given in and accepted the uniform as an unavoidable accident, a chronic disease of fate, conspicuous but not painful. The most significant contradiction of his life has finally been transformed into the sole element of continuity.

â¢Â â¢Â â¢Â

I

t's a clear morning in early April; the rounded leather boot tops of the soldiers marching in review gleam with every step. Egitto isn't yet accustomed to the clarity, full of promise, that Belluno's sky flaunts on days like this. The wind that rolls down from the Alps carries with it the arctic cold of glaciers, but when it subsides and stops whipping the banners around, you realize that it's unusually warm for that time of year. In the barracks there was a big debate about whether or not to wear their scarves and in the end it was decided not to; the word was shouted out from corridor to corridor and from one floor to another. The civilians, however, are undecided about what to do with their jackets, whether to wear them over their shoulders or carry them over their arms.

Egitto lifts his hat and runs his fingers through his damp, sweaty hair. Colonel Ballesio, standing to his left, turns to him and says, “That's disgusting, Lieutenant! Dust off your jacket. It's full of those flakes again.” Then, as if Egitto weren't capable of doing it himself, the colonel brushes off his back with his hand. “What a mess,” he mutters.

There's a break. Those, like Egitto and Ballesio, who have a seat in the stands, can sit down. Egitto can finally roll down his socks at the ankles. The itching subsides, but only for a few seconds.

“Listen to this,” Ballesio starts off. “The other day my little daughter started marching around the living room. âLook, Daddy,' she said, âlook at me, I'm a colonel too.' She'd dressed up in her school smock and a beret. Well, you know what I did?”

“No, sir. What?”

“I gave her a good spanking. I'm not kidding. Then I yelled at her and said I never wanted to see her mimicking a soldier again. And that no one would enlist her anyway because of her flat feet. She started to cry, the poor thing. I couldn't even explain to her why I got so angry. But I was beside myself, believe me. Tell the truth, Lieutenant: in your opinion, am I a bit burned-out?”

Egitto has learned to be wary of the colonel's requests to be frank. He replies: “Maybe you were just trying to protect her.”

Ballesio makes a face, as if Egitto has said something stupid. “Could be. So much the better. These days I'm afraid I may not be all there, if you know what I mean.” He stretches his legs, then unashamedly adjusts the waistband of his undershorts through his pants. “You hear about those guys who overnight end up with their brains fucked up. Do you think I should get one of those neurological checkups, Lieutenant? Like an EKG or something?”

“I don't see any reason to, sir.”

“Maybe you could check me over. Examine my pupils and so on.”

“I'm an orthopedist, Colonel.”

“But still, they must have taught you something!”

“I can suggest the name of a colleague, if you'd like.”

Ballesio grunts. He has two deep grooves around his lips that inscribe his face like the snout of a fish. When Egitto first met him he wasn't so worn-out.

“Your fastidiousness is catching, Lieutenant, did I ever tell you? That must be why you're in the state you're in. Just relax for once, take things as they come. Or find a hobby. Have you ever thought about having kids?”

“Excuse me?”

“Kids, Lieutenant.

Kids

.”

“No, sir.”

“Well, I don't know what you're waiting for. A kid would cleanse your head of certain thoughts. I see you, you know? Always there brooding. Just look how ready and willing these troops are, such eager beavers!”

Egitto follows Ballesio's line of sight, to the military band and beyond, where the lawn begins. A man standing in the crowd catches his attention. He's carrying a child on his shoulders and standing stiffly, chest out, in a strangely military posture. A familiar face always makes itself known to the lieutenant through a vague fear, and all of a sudden Egitto feels uneasy. When the man raises a fist to his mouth to cough, he recognizes Marshal René. “That guy over there, isn't he . . . ?” He stops.

“Who? What?” the colonel says.

“Nothing. Sorry.”

Antonio René. On the last day, at the airport, they took their leave with a formal handshake and since then Egitto hasn't thought of him, at least not specifically. His memories of the mission mostly assume a collective quality.

He loses interest in the parade and applies himself to observing the marshal from afar. René hasn't made his way deep enough through the crowd to reach the front rows; most likely there's not much to see from where he is. From where he sits on his father's shoulders, the child points to the soldiers, the banners, the men with the instruments, clutching René's hair like reins. The hair, that's what's changed. In the valley the marshal's head was closely shaven; now his brown, slightly wavy hair nearly covers his ears. René is another fugitive from his past. He too has altered his looks so he won't recognize himself.

Ballesio is saying something about a tachycardia that he surely doesn't have. Egitto replies absently, “Stop by to see me in the afternoon. I'll prescribe something for the anxiety.”

“Are you completely out of your mind? That stuff makes your cock limp!”

Three unarmed fighter-bombers whiz by, low, over the parade ground, then soar sharply, leaving colorful streaks in the sky. They turn onto their backs and cross paths. The child on René's shoulders is awestruck. Like his, hundreds of heads turn upward, all except those of the soldiers in formation, who go on staring firmly at something that only they can see.

â¢Â â¢Â â¢Â

A

t the end of the ceremony Egitto makes his way back through the crowd. Families linger in the square and he has to sidestep them. He gives a perfunctory handshake to those who try to stop him, and he keeps an eye on the marshal. For a moment Egitto thought he was about to turn and leave, but he's still there. Egitto joins him and takes off his hat once he's standing in front of him. “René,” he says.

“Hello, Doc.”

The marshal sets the child down on the ground. A woman comes up and takes him by the hand. Egitto nods at her, but she doesn't nod back; she tightens her lips and backs away. René nervously rummages in his jacket pocket, pulls out a pack of cigarettes and lights one. That's one thing that hasn't changed: he still smokes the same slender white cigarettes, a woman's cigarettes.

“How are you, Marshal?”

“Good, good,” René responds quickly. Then he repeats it, but with less confidence: “Good. Trying to scrape along.”

“That's right. We have to carry on.”

“And you, Doc?”

Egitto smiles. “Me too, getting by.”

“So they didn't give you too much trouble over that incident?” It's as if pronouncing those words costs him a great deal of effort. He doesn't seem to care much about the answer, in fact.

“A disciplinary action. Four months' suspension from the service and some inconclusive hearings. Those were the real punishment. You know how that goes.”

“Good for you.”

“Good for me, right. You decided to quit instead.”

He could have said it differently, used another word instead of

quit

: change jobs, resign.

Quit

meant giving up. René doesn't seem to be bothered, though.

“I work in a restaurant. Down in Oderzo. I'm the maître d'.”

“Still in command, then.”

René sighs. “In command. Right.”

“And the other guys?”

René's foot scrapes at a tuft of grass in a crack in the pavement. “I haven't seen them in a while.”

The woman is now gripping his arm, as if wanting to drag him away, rescue him from Egitto's uniform and the memories they have in common. She shoots quick, resentful glances at the lieutenant. René, however, avoids looking at him, though for an instant his eyes focus on the quivering black plume attached to his hat and Egitto seems to glimpse a trace of nostalgia in him.

A cloud covers the sun and the light suddenly grows dim. The lieutenant and the ex-marshal fall silent. They shared the most important moment of their lives, the two of them, standing as they are now, but in the middle of a desert and a circle of armored tanks. Can it be they have nothing left to say to each other?

“Let's go home,” the woman whispers in René's ear.

“Of course. I don't want to keep you. Good luck, Marshal.”

The child holds out his arms to René, asking to be put back on his shoulders. He's whimpering, but it's as if his father doesn't see him. “You can come and find me at the restaurant,” he says. “It's a good place. Fairly good.”

“Only if you give me special treatment.”

“It's a good place,” René repeats absently.

“I'll be sure to come,” Egitto pledges. But it's clear to both of them that it's one of those countless promises that are never kept.