The House Of Silk (27 page)

‘What is this clue?’ I asked.

‘I have it with me. It was, as I say, my wife who found it in the dormitory. She was turning the mattresses – we do it once a month to air and to fumigate them. Some of the boys have lice … we wage a constant war against them. At any event, the bed occupied by Ross is now taken by another child, but there was a copybook concealed there.’ Fitzsimmons took out a thin book with a rough cover, faded and crumpled. There was a name written in a childish hand, in pencil on the front.

‘Ross could not read or write when he came to us, but we had endeavoured to teach him the rudiments. Each child in the school is given a copybook and a pencil. You will see inside his that he has forsaken his exercises. It is all very messy. He seems to have passed much of his time scribbling. But on examining it, we discovered this and it seemed to us to have significance.’

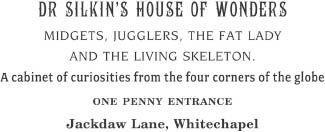

He had opened the book in the middle to show a sheet of paper, neatly folded and slipped inside as if the intention had been deliberately to conceal it. Taking it out, he unfolded it and spread it on the table for me to see. It was an advertisement, a cheap flyer for an attraction of the sort that I knew had once sprung up around such areas as Islington and Cheapside but which had since become rarer. The text was decorated by images of a snake, a monkey and an armadillo. It read:

‘I would, of course, discourage my boys from ever entering such a place,’ the Reverend Fitzsimmons said. ‘Freak shows, music halls, one penny gaffs … it astonishes me that a great city such as London will tolerate such entertainments, where everything that is vulgar and unnatural is celebrated. The lessons of Sodom and Gomorrah spring to mind. I say this to you, Dr Watson, as it may be that Ross concealed this advertisement for no other reason than that he knew it was against the very spirit of Chorley Grange. It may have been an act of defiance. He was, as my wife told you, a very wilful boy—’

‘But it may also have a connection for him,’ I broke in. ‘After he left you, he sought refuge with a family in King’s Cross and also with his sister. But we have no idea where he was before. It could be that he fell in with this crowd.’

‘Exactly. I feel sure it is worthy of investigation which is why I brought it to you.’ Fitzwilliams collected his things and got to his feet. ‘Is there any possibility that you will be in communication with Mr Holmes?’

‘I am still hoping that he will contact me in some way.’

‘Then perhaps you will see what he makes of it. Thank you for your time, Dr Watson. I am very, very shocked about young Ross. We will pray for him in the school chapel this Sunday. No. There is no need to show me out. I will find my way.’

He took up his coat and scarf and left the room. I stared at the page, allowing my eyes to travel across the gaudy lettering and the crude illustrations. I think I must have read it two or three times before I saw what should have been obvious to me from the start. But there was no mistaking it. Dr Silkin’s House of Wonders. Jackdaw Lane. Whitechapel.

I had just found the House of Silk.

A Message

My wife returned to London the following day. She had sent me a telegram from Camberwell to inform me of her arrival and I was waiting for her at Holborn Viaduct when her train drew in. I have to say that I would not have left Baker Street for any other reason. I was still certain that Holmes would attempt to reach me and dreaded the idea of his making his way to his lodgings, with all the dangers that would entail, only to find me not in. But nor could I consider allowing Mary to cross the city unattended. One of her greatest virtues was her tolerance, the way she put up with my long absences in the company of Sherlock Holmes. Never once did she complain, although I know she worried that I was putting myself in danger, and I owed it to her now to explain what had happened while she had been away and to inform her that, regretfully, it might be a while yet before we could be permanently reunited. And I had missed her. I looked forward to seeing her again.

It was now the second week in December and, after the bad weather that had begun the month, the sun was out and although it was very cold, everything was ablaze with a sense of prosperity and good cheer. The pavements were almost invisible beneath the bustle of families arriving from the countryside and bringing with them wide-eyed children in numbers that might have populated a small city themselves. The ice-rakers and the crossing-sweepers were out. The sweetmeat and grocer shops were gloriously festooned. Every window carried advertisements for goose clubs, roast beef clubs and pudding clubs and the very air was filled with the aroma of burned sugar and mincemeat. As I climbed down from my brougham and made my way into the station, pushing against the crowd, I reflected on the circumstances that had alienated me from all this activity, from the day-to-day pleasures of London in the festive season. That was perhaps the disadvantage of my association with Sherlock Holmes. It drew me into dark places where, in truth, nobody would choose to go.

The station was no less crowded. The trains were on time, the platforms filled with young men carrying parcels, packages and hampers, scurrying around as excitably as Alice’s white rabbit. Mary’s train had already arrived and I was briefly unable to locate her as the doors opened, pouring yet more souls into the metropolis. But then I saw her and, as she climbed down from her carriage, an event occurred that caused me a moment of disquiet. A man appeared, shuffling across the platform as if about to accost her. I could only see him from the back and, apart from an ill-fitting jacket and red hair, would have been unable to identify him again. He seemed to speak briefly to her, then boarded the train, disappearing from sight. But perhaps I was mistaken. As I approached her she saw me and smiled and then I had taken her in my arms and together we were walking towards the entrance where I had told my driver to wait.

There was much that Mary wanted to tell me of her visit. Mrs Forrester had been delighted to see her and the two of them had become the closest of companions, their relationship of governess and employer being long behind them. The boy, Richard, was polite and well behaved and, once he had begun to recover from his sickness, charming company. He was also an avid reader of my stories! The household was just as she remembered it, comfortable and welcoming. The whole visit had been a success, apart from a slight headache and sore throat that she had herself picked up in the last few days and which had been exacerbated by the journey. She looked tired and, when I pressed her, she complained of a sense of heaviness in the muscles of her arms and legs. ‘But don’t fuss over me, John. I’ll be quite my old self after a rest and a cup of tea. I want to hear all your news. What is this extraordinary business I’ve been reading about with Sherlock Holmes?’

I wonder to what extent I should blame myself for not examining Mary more closely. But I was preoccupied and she herself made light of her illness. And I was thinking also of the strange man who had approached her. It is quite likely that, even had I known, there would have been nothing that I could do. But even so, I have always had to live with the knowledge that I took her complaints too lightly and failed to recognise the early signs of the typhoid fever which would take her from me all too soon.

It was she who brought up the message, just after we set off. ‘Did you see that man just now?’ she asked.

‘At the train? Yes, I did see him. Did he speak to you?’

‘He addressed me by name.’

I was startled. ‘What did he say?’

‘Just “Good morning, Mrs Watson.” He was very uncouth. A working man, I would have said. And he pressed this into my hand.’

She produced a small cloth bag which she had been clutching all the time but which she had almost forgotten in the pleasure of our reunion and our necessary haste leaving the station. Now she handed it to me. There was something heavy inside the bag, and I thought at first that it might be coins for I heard the clink of metal, but on opening it and pouring the contents into the palm of my hand, I found myself holding three solid nails.

‘What is the meaning of this?’ I asked. ‘Did the man say nothing more? Can you describe him?’

‘Not really, my dear. I barely glanced at him as I was looking at you. He had chestnut hair, I think. And a dirty, unshaven face. Does it matter?’

‘He said nothing else? Did he demand money?’

‘I told you. He greeted me by name; nothing more.’

‘But why on earth would anyone give you a bag of nails?’ The words were no sooner out of my mouth than I understood and let out a cry of exultation. ‘The Bag of Nails! Of course!’

‘What is it, my dear?’

‘I believe, Mary, that you may have just met Holmes himself.’

‘It looked nothing like him.’

‘That is exactly the idea!’

‘This bag of nails means something you?’

It meant a great deal. Holmes wanted me to return to one of the two public houses that we had visited when we were searching for Ross. Both had been called The Bag of Nails, but which one did he have in mind? It would surely not be the second one, in Lambeth, for that was where Sally Dixon had worked and it was known to the police. All in all, the first one, in Edge Lane, was more likely. For he was certainly afraid of being seen; that much was implicit in the manner he had chosen to communicate with me. He had been in disguise and if anyone had seen the approach and tried to apprehend Mary or myself on the station platform, they would have found nothing but a cloth bag with three carpenter’s nails and no indication at all that a message had been passed.

‘My dear, I’m afraid I am going to have to abandon you the moment we are home,’ I said.

‘You are not in any danger are you, John?’

‘I hope not.’

She sighed. ‘Sometimes I think you are fonder of Mr Holmes than you are of me.’ She saw the look on my face and patted my hand gently. ‘I’m only being pleasant with you. And you don’t need to come all the way to Kensington. We can stop at the next corner. The driver can bring in my bags and I can see myself home.’ I hesitated and she looked at me more seriously. ‘Go to him, John. If he resorted to such lengths to send a message, then he must be in trouble and needs you as he has always needed you. You cannot refuse.’

And so I parted company from her, not just taking my life in my hands but almost losing it as I slipped out in the traffic, coming close to being run over by an omnibus in the Strand. For it had occurred to me that, if Holmes was afraid of being followed, I should be too, and it was therefore vital that I should not be seen. I dodged between various carriages and finally reached the safety of the pavement where I looked carefully about me before turning back the way I had come, arriving in that forlorn and sorry part of Shoreditch about thirty minutes later. I remembered the public house well. A rundown place that looked little better in the sunlight than it had in the fog. I crossed the street and went in.

There was one man sitting in the saloon bar and it was not Sherlock Holmes. To my great surprise and somewhat to my mortification, I recognised the man called Rivers who had assisted Dr Trevelyan at Holloway Prison. He was no longer wearing his uniform, but his vacant expression, sunken eyes and unruly ginger hair were unmistakable. He was slouching at a table with a glass of stout.

‘Mr Rivers!’ I exclaimed.

‘Sit down with me, Watson. It’s very good to see you again.’

It was Holmes who had spoken – and in that second I understood how I had been deceived and how he had effected his escape from prison in front of my very eyes. I confess that I almost fell into the seat that he had proffered, seeing, with a sense of haplessness, the smile that I knew so well, beaming at me from beneath the wig and the make-up. For that was the wonderment of Holmes’s disguises. It wasn’t that he used a great deal of theatrical trickery or camouflage. It was more that he had a knack of metamorphosing into whatever character he wished to play and that if he believed it, you would believe it too, right up to the moment of revelation. It was like gazing at an obscure point on a distant landscape, at a rock or a tree which had taken on the shape, perhaps, of an animal. And yet once you had drawn closer and seen it for what it was, it would never deceive you again. I had sat down with Rivers. But now it was obvious to me that I was with Holmes.