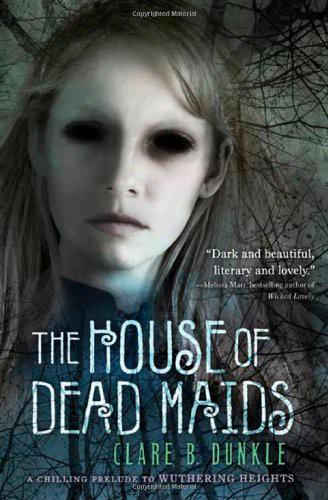

The House of Dead Maids

Read The House of Dead Maids Online

Authors: Clare B. Dunkle

THE

HOUSE

OF

DEAD MAIDS

Books by Clare B. Dunkle

THE HOLLOW KINGDOM TRILOGY:

The Hollow Kingdom

BOOK I

Close Kin

BOOK II

In the Coils of the Snake

BOOK III

By These Ten Bones

HOUSE

OF

DEAD MAIDS

CLARE B. DUNKLE

illustrations by

PATRICK ARRASMITH

HENRY HOLT AND COMPANY | NEW YORK

Henry Holt and Company, LLC

Publishers since 1866

175 Fifth Avenue

New York, New York 10010

www.HenryHoltKids.com

Henry Holt

®

is a registered trademark of Henry Holt and Company, LLC.

Text copyright © 2010 by Clare B. Dunkle

Illustrations copyright © 2010 by Patrick Arrasmith

All rights reserved.

Distributed in Canada by H. B. Fenn and Company Ltd.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Dunkle, Clare B.

The house of dead maids / Clare B. Dunkle ;

[illustrations by Patrick Arrasmith].

p. cm.

Summary: Eleven-year-old Tabby Aykroyd, who would later serve as housekeeper for thirty years to the Brontë sisters, is taken from an orphanage to a ghost-filled house, where she and a wild young boy are needed for a pagan ritual.

ISBN 978-0-8050-9116-8

[1. Household employees—Fiction. 2. Ghosts—Fiction. 3. Rites and ceremonies—Fiction. 4. Orphans—Fiction. 5. Brontë family—Fiction. 6. Great Britain—History—19th century—Fiction.] I. Arrasmith, Patrick, ill. II. Title.

PZ7.D92115Hou 2010 [Fic]—dc22 2009050769

First Edition—2010

Book designed by April Ward

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Sometimes, when the ghosts

and goblins swarm,

all a child can count on

is the help of another child.

I love you, Jennifer.

You’ve always been there.

THE

HOUSE

OF

DEAD MAIDS

I was not the first girl she saw, nor the second, and as to why she chose me, I know that now: it was because she did not like me. She sat like a magistrate on the horsehair sofa, examining me for failings. “Stop staring,” she snapped. “You’d think I was a world’s wonder.”

I looked away, thinking my own thoughts. She couldn’t stop me from doing that. She had a sweep of thick brown hair tucked up into a bun, and she wore a somber black wool dress. Her hands were soft: lady’s hands. Her face was anything but soft.

It looked cold and hard and pale, like stone. Like a newly placed tombstone.

“I mustn’t take a half-wit, though,” she said reluctantly, as if she would like to do it. She seemed to consider idiocy the greatest point in my favor.

“Oh, our Tabby’s no half-wit,” countered Ma Hutton. “She just has that look. You did say you wanted to see an ugly one, miss.”

I stared at the braided rag rug, thinking about the black dress. She was in mourning. For whom? She was a handsome woman and might once have been beautiful.

“Tabby’s the best knitter in the school,” Ma Hutton was proclaiming. “She can turn out a sock in a day. And handy! She’s stronger than she looks, and she sews a pretty buttonhole, miss.”

“No scars,” interrupted the woman. “You can swear to that, you said. This is of the utmost importance. I cannot bear deformity.”

“She hasn’t a scar that I recollect,” Ma Hutton said slowly, beginning to fidget with her hands. She was wanting to knit, I knew. She hated to put down her knitting. “Tabby hasn’t worked in the fields, have you, child? She’s done light work.”

“No broken bones? I must be positive on this point.”

Ma Hutton signed for me to speak.

“I’ve broken naught, miss,” I answered, meeting the woman’s gaze as a token I was telling the truth. She winced, and her eyes glittered. When a dog looked like that, people knew to leave it alone.

“No relations, you said,” she reminded Ma Hutton, turning away from me.

“None, miss,” Ma Hutton assured her. “Tabby doesn’t even know where she’s from.”

Before a kindly soul had brought me to Ma Hutton’s knitting school, I had grown up in the kitchens of big houses, polishing boots and running errands. I had been told that my surname was Aykroyd, although I knew no one else who had it. Most likely it had been my mother’s name. I could dimly recall a face when I thought of

mother

, although the face was so young and frightened that it confused me. The one thing I held as a certainty had been dinned into my ears by angry cooks and housekeepers. I had no father at all, quite a failing in a little child.

“She’ll do,” said the woman. “Tell her to fetch her things.”

I hadn’t much to take from the room I shared with eight other girls, except an old greatcoat someone had given me out of charity and the pattens, or wooden clogs, which we wore outside in the mud.

Then I went to the room where Ma’s students sat knitting and bade them good-bye.

One of the girls who had been passed over came to whisper with me in the doorway. “She’s been here before, that woman,” she said. “She took Izzy with her last time.”

I said, “I don’t remember a girl named Izzy.”

“It was years ago, when I was new here. Izzy must be grown now, and run away with a soldier most likely, and miss needs a new girl to beat with her hairbrush. I got a shivery feeling when she talked to me. Didn’t you? I wouldn’t be you for a thousand pounds.”

I returned to the parlor. Money had changed hands while I was gone, a substantial sum by the look of things because Ma Hutton’s typical good humor had blossomed into rapture. She went so far as to wax sentimental over me, though I had never been a favorite, and bade me keep my knitting needles and my ball of worsted in its little rag pocket as a parting gift from the school. “And wrap up warm,” she counseled, pulling the greatcoat around me. “I don’t doubt you’ll have a long journey.” But where we were going, I hadn’t the heart to ask, and no one bothered to say.

We were in April then, but the spring had been

cold, and the day was misty, as dark at noon as it had been at dawn. The houses across the street looked gray and insubstantial, shadows rather than stone.

The woman in black pushed me towards an open cart waiting in the lane. Its driver had taken the precaution of bringing a lighted lantern with him, and he swung down from the seat and held up the light to view me. “What have you brought us?” he boomed. “Why, it’s a quaint little body, to be sure!”

It isn’t that I’m so bad to look at, for my nose is straight and I have all my teeth, but my eyelashes are sparse and pale, and my eyes are no particular color. Add to that my stature, which is very small, and you’ll find folks who call me a quaint body yet.

The man who bent over me was long-limbed, with a round face buffeted red by wind and weather. “Pleased to meet you, little maidie,” he said, shaking hands. “My name’s Arnby. You look a right canny lass. How old would you happen to be?”

“I’m eleven, sir. My name’s Tabitha Aykroyd, but people call me Tabby.”

“So many years packed in such a tiny frame! I can tell she’s got us a good one. Now, listen, little maid. If she gives you any cause for grief,” and he

nodded towards the woman who stood behind me, “just you come tell me all about it, and I’ll soon set her to rights.”

This alarmed me, as it seemed an impertinence. I didn’t want to start off badly with my new employer. “Please, miss,” I said, turning to the woman, “what am I to call you?”

She made no reply, but pushed past me and scrambled awkwardly onto the seat of the cart. Arnby stood by and laughed to see her do it.

“She’d tell you to call her Miss Winter if she could swallow her pride to speak,” he said. “But call her the old maid, dearie. Everyone else does.”

Our journey took two long, tedious, dreadfully foggy days. The creeping mist swallowed us up and showed neither landmark nor horizon, and often Arnby had to walk ahead and lead the horse by the bridle. It seemed to me that we jolted up and down and went nowhere at all. I tried to knit my sock, but the cart shook so that it made me ill.

“It’s wondrous weather,” declared Arnby once, climbing back onto his seat. “The season’s so late that the ewes have lost lambs, and the planting’s only half done. The old earth’s tired, that’s what, and last year’s storms and floods have vexed her. People don’t think on the earth enough, and that’s

what causes the trouble. They plow at her and rip food from her, toss their trash and middens on her, bore mine holes into her, and never a word of thanks do they say.”