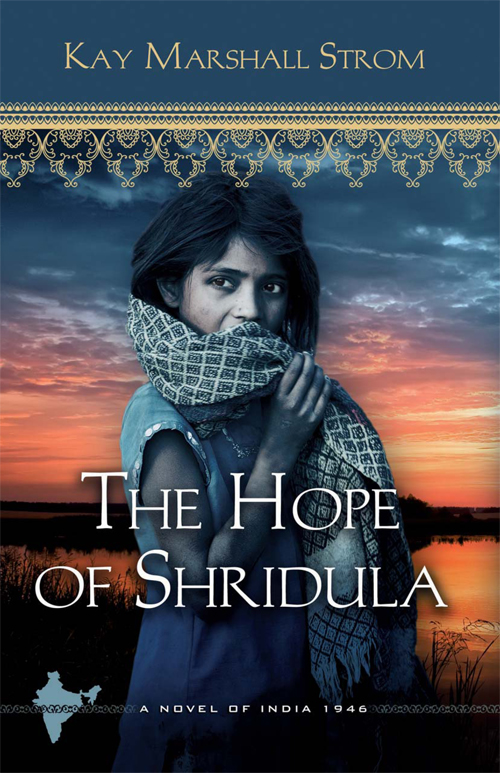

The Hope of Shridula

Read The Hope of Shridula Online

Authors: Kay Marshall Strom

The Hope of

Shridula

The Hope of

Shridula

Series

Nashville, Tennessee

The Hope of Shridula

Copyright © 2012 by Kay Marshall Strom

ISBN-13: 978-1-4267-0909-8

Published by Abingdon Press, P.O. Box 801, Nashville, TN 37202

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form,

stored in any retrieval system, posted on any website,

or transmitted in any form or by any means—digital,

electronic, scanning, photocopy, recording, or otherwise—without

written permission from the publisher, except for brief

quotations in printed reviews and articles.

The persons and events portrayed in this work of fiction

are the creations of the author, and any resemblance

to persons living or dead is purely coincidental.

Published in association with the Books & Such Literary Agency,

Janet Kobobel Grant,

5926 Sunhawk Drive, Santa Rosa, CA 95409

Cover design by Anderson Design Group, Nashville, TN

Scripture quotations are taken from the King James or Authorized

Version of the Bible.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data requested

Strom, Kay Marshall, 1943-

The hope of Shridula / Kay Marshall Strom.

pages cm. — (Blessings in India series ; book 2)

ISBN 978-1-4267-0909-8

1. Caste—India--Fiction. 2. Peonage—India—Fiction. 3. Families—India—Fiction. 4. Christians—India—Fiction. 5. India—History—20th century—Fiction. I. Title.

PS3619.T773H67 2012

813'.6—dc23

2011048177

Printed in the United States of America

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 / 17 16 15 14 13 12

I gratefully dedicate this book to the Dalits in India,

who continue to fight for respect and equality and their constitutional

rights. I wish I could list all of you, but such

a listing would require volumes.

God knows each of you by name.

May His grace and peace be with you all.

To say that India has captured my heart would be wrong. My heart has been captured all right, but not by the land. It is the dear people of India who bring me such joy. Most of the ones I am privileged to know personally come from the lowest strata of the caste social system—Dalits, as they prefer to be called today. In addition, most of these are also members of the Christian minority. It is through their eyes that I am beginning to make out the India that was, the India that is today, and with God's grace, the India that is still to come.

I never could have begun this project without the encouragement and assistance of so many who have willingly shared with me their stories, their heartaches, their hopes and dreams, and their emerging opportunities.

In addition to Kolakaluri Sam Paul, who first planted the seed for this project, and others I have named before— Dr. B. E. Vijayam, Mary Vijayam, Bishop Moses Swamidas, P. T. George, and Jebaraj Devashayam—I would like to express my appreciation to the family of Ruby Irene Fletchall. I never actually met Ruby Irene, but she and her husband were missionaries with the Kanarese Biblical Seminary in India during the time period considered in this book. Her family generously shared a detailed letter she wrote home that provided me with an invaluable insider's view of many details of life prior to India's independence.

To Ramona Richards, my Abingdon editor, thank you for your expertise and your patience. To Kathy Force, thank you for your time and your sharp reader's eye. To author/writing instructor Linda Clare, thank you for being my wonderful critique partner.

And to my husband, Dan Kline, thank you for your loving support, for all your help, for being my traveling companion. You are always my best editor. I could not do this without you.

Shridula

1

South India

May 1946

T

he last of the straggling laborers hefted massive bundles of grain onto their weary heads and started down the path toward the storage shed. Only twelve-year-old Shridula remained in the field. Frantically she raced up and down the rows, searching through the maze of harvested wheat stalks.

Each time a group of women left, the girl tried to go with them, her nervous fear rising. Each time Dinkar stopped her. The first time she had tried to slip in with the old women at the end of the line the overseer ordered, "Shridula! Search for any water jars left in the fields." Of course she found none. She knew she wouldn't. What water boy would be fool enough to leave a jar behind?

By the time the girl finished her search, twilight shrouded the empty field in dark shadows. Shridula hurried to grab up the last bundle of grain. Its stalk tie had been knocked undone, and wheat spilled out across the ground. Quickly tucking the tie back together, Shridula struggled to balance the bundle up on her head. It shifted . . . and sagged . . . and sank down to her shoulders.

Shridula was not used to managing so unwieldy a head load. In truth, she wasn't used to working in the field at all. Her father made certain of that. This month was an exception, though, for it was the month of the first harvest. That meant everyone spent long days in the sweltering fields—including Shridula.

The girl, slight for her twelve years, possessed a haunting loveliness. Her black hair curled around her face in a most intriguing way that accented her piercing charcoal eyes. Stepping carefully, she picked her way out of the field and onto the path. Far up ahead, she could barely make out the form of the slowest woman. If she hurried, she still might be able to catch up with her. The thought of walking the path alone sent a shudder through the girl.

Shridula tried to hurry, but she could not. With each step, her awkward burden slipped further down toward her shoulders. She could hardly see through the stalks of grain that hung over her eyes.

"Please, allow me to lend you a hand."

Shridula caught her breath. How well she knew that voice! It was Master Landlord, Boban Joseph Varghese.

Afraid to lift her head, Shridula peeked out from under the mass of grain stalks. Master Landlord, fat and puffy-faced, stood on the other side of the thorn fence, ankle-deep in the stubbly remains of the wheat field. His old-man eyes fastened on her.

Shridula reached up with both hands and grabbed at the bundle on her head.

"Do not struggle with the load," Boban Joseph said, his voice as slippery-smooth as melted butter. "The women can retie it tomorrow. Let them carry it to the storehouse on their own worn-out old heads."

A shiver of dread ran through Shridula's thin body. She must be careful. Oh, she must be so very careful!

All day long, as fast as the women could carry bundles of grain from the fields, Ashish had gathered them up. He separated the bundles and propped the sheaves upright side by side in the storage shed. Everything must be done just right or the grain wouldn't dry properly. One after another after another after another, Ashish stacked the grain sheaves. By the time the last woman brought in the last bundle, by the time he stood the last of the sheaves upright, by the time he closed the shed door and squeezed the padlock shut, then kicked a rock against the door for good measure and headed back to his hut, the orange shards of sunset had already disappeared from the sky.

A welcoming glow from Zia's cooking fire beckoned to Ashish. He watched as his wife grabbed out a measure of spices and sprinkled them into the boiling rice pot. But this night something wasn't right. This night Zia worked alone.

"Where is Shridula?" Ashish asked his wife.

Zia bent low over the fire and gave the pot such a hard stir it almost tipped over.

"She has not yet returned from the fields," Zia said in a voice soft and even. But after so many years together, Ashish wasn't fooled.

The glow of firelight danced across Zia's features and cast the furrows of her brow into dark shadows. Ashish ran a gnarled hand over the deep crevices of his own aging face. He yanked up his

mundu—

his long, skirt-like garment—and pulled it high under his protruding ribs, untying the ends and retying them more tightly.

"She should not have to walk alone," he said. "I will go back." Ashish spoke with exaggerated nonchalance. He would remain calm for Zia's sake.

"All night!" Ashish said to his daughter when she came in at first light. He spoke in a low voice, but it hung heavy with rebuke. "Gone from your home the entire night!"

Overhead, Ashish's giant

neem

tree reached its branches out to offer welcome shelter from the early morning sun. Twenty-eight years earlier, on the day of his wedding, Ashish had planted that tree. Back then, it was no more than a struggling sprout. Yet even as he placed it in the ground, he had talked to Zia of the refreshing breezes that would one day rustle through its dark green leaves. He promised her showers of sweetly fragrant blossoms to carpet the barren packed dirt around their hut.

But no breeze pushed its way through this morning's sweltering stillness, and the relentless sun had long since scorched away the last of the white blossoms. Still, the tree was true to its promise. Its great leaves sheltered Ashish's distraught daughter from curious eyes.

Zia stared at the disheveled girl:

sari

torn, smudged face, wheat clinging to her untidy hair. Zia stared, but said nothing.

"Master Landlord told me I must go with him." Shridula trembled and her eyes filled with tears. "I said no, but he said I had to obey him because he owns me. Because he owns all of us, so we must all do whatever he says."

"Please, Daughter, stay away from Master Landlord," Ashish pleaded.

"I did,

Appa!"

Shridula struggled to fight back tears. "I dropped the bundle of grain off my head and ran away from him, just as you told me to. He tried to catch me, but I ran into the field and sneaked into the storage shed the way you showed me and hid there. All night, I hid in the wheat shocks."

"That new landlord!" Zia clucked her tongue and shook her head. "He is worse than the old one ever was!"

Zia reached over to brush the grain from her daughter's hair, but Shridula pushed her mother's hand away. Her dark eyes flashed with defiance. "Someday I will leave here!" she announced. "I will not stay a slave to the landlord!"

Boban Joseph was indeed worse than his father. Mammen Samuel Varghese had been an arrogant man, a heartless landowner with little mercy for the hapless Untouchables unfortunate enough to be caught up in his money-lending schemes.

Yet Mammen Samuel took great pride in his family's deep Christian roots—he could trace his ancestry all the way back to the first century and the Apostle Thomas. He also clung tightly to the fringes of Hinduism. The duality served him well. It promoted his status and power, yet it also fattened his purse. Even so, Mammen Samuel Varghese had not been a happy man. He seethed continually over the sea of wrongs committed against him, some real and others conjured up in his mind.

Still, it had always been Mammen Samuel's habit to think matters out thoroughly. In every situation, he first considered the circumstances in which he found himself, then measured each potential action and carefully weighed its consequence. It's what he had done when he lent Ashish's father the handful of rupees that led to his family's enslavement. Only after such consideration would Mammen Samuel make a decision. His son Boban Joseph did no such thing.

No, Young Master Landlord was not his father.

During the years of Ashish's and Zia's childhood, Mammen Samuel Varghese maintained tight control over his house and his settlement of indebted slaves. But age did not wear well on him. And the greater Mammen Samuel's decline, the more wicked and cruel Boban Joseph became.

Soon after Ashish took Zia as his wife, the elder landlord began to release one responsibility after another to his first son. Boban Joseph eagerly snatched up each one. Soon Boban Joseph began to grasp control of matters behind his father's back—always for his own personal advantage. This greatly displeased Mammen Samuel. Even more, it worried him. Boban Joseph was his heir, but something had to be done to place controls around him.

As the season grew hotter and the harvest more demanding, Boban Joseph accepted the agreement reached between the laborers and his father requiring them to work a longer day—begin before dawn and continue until after dark. But he refused to honor his father's reciprocal agreement with the workers—to allow them to rest during the two hottest hours of the afternoon.

Only when a young man fell over and died of heatstroke while swinging his scythe, and the next day one of the best workers fell off his plow in exhaustion after begging in vain for shade and water, did Boban Joseph reluctantly agree to grant a midday break. "Only long enough for a cold meal out of the sun and not a minute more!" he instructed the overseer. (Since Boban Joseph spent his afternoons stretched out across the bed in the coolness of his own room, he never knew that Dinkar allowed the workers extra time in the shade.)

"Stay away from the fields today," Ashish told Shridula.

"But the harvest—"

"The harvest is not your worry, Daughter. Busy yourself with work here in the settlement. Make it your job to be of help to weary laborers."

"How can I do that?"

"Fill water jars for the women. Gather twigs and lay them beside the cold cooking pits."

Zia scowled at her husband. "It is not right that you stand the girl up in front of Master Landlord's revenge," she said. "He is a spiteful man. And brutal."

Ashish knew that. More than anyone, he knew it.

"Master Landlord knows Shridula is your daughter," Zia pleaded. "And he will never forget."

She was right, of course. For forty years, Boban Joseph had demonstrated a seething resentment toward Ashish's family. He clung tightly to his own family's humiliation that had been brought about when Ashish's parents, Virat and Latha, dared escape from Mammen Samuel's laborer settlement. Boban Joseph, then hardly more than a boy, greatly resented his father's timid response to their capture and return. He didn't hide his feelings; he let it be known to everyone that he considered his father's actions shameful and cowardly. Boban Joseph himself had captured the runaway slaves and dragged them back in bonds. Yet his father ignored his demands to have them killed. Mammen Samuel wouldn't even order a public flogging.

"You will stay here in the settlement today," Ashish told his daughter. "You will be a servant to the workers, not to the master."

"Yes,

Appa,"

Shridula said.

"But watch out for the landlord. Should he come around, run to the forest and hide yourself. And do not come out until I am back."