The Hollywood Economist (7 page)

Read The Hollywood Economist Online

Authors: Edward Jay Epstein

Tags: #Business & Economics, #Industries, #Media & Communications

Disney, which raked in a large percent of the nearly half-billion gross through its ownership of Buena Vista International and Buena Vista Home Entertainment, of course made money, despite the paper losses in its off-the-books entity for

Gone in 60 Seconds

. The net players of course all got paid their fixed compensation. They had willingly agreed to the terms in their contract, which defined their net, and their contracts were almost certainly vetted by their talent agents, business managers, and lawyers, who deal day in and day out with similar contracts. So if the net players are deceived by the contractual definition of net profits, it is, like so many other aspects of Hollywood relationships, a self-deception. They want to believe, no matter what their lawyers, agents, and business managers tell them, that they will participate in the profits of their product.

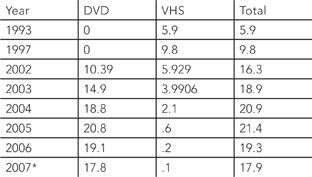

THE RISE OF DVDS

MPA Studio Revenues from DVD vs.VHS

Studio receipts

(Billions of dollars)

*The studios stopped furnishing these revenue numbers to the MPA in 2008.

Hollywood studios never give participants—not even ones as powerful as Arnold Schwarzenegger, Tom Cruise, Tom Hanks, Jerry Bruckenheimer, Steven Spielberg, or even Pixar Animation Studios—an unadulterated percentage of the box office

gross, or the video store gross, or any other retail gross. As one top Viacom executive explained, “The first truism of Hollywood is: Nobody gets gross—not even a top first dollar gross player.”

What the top gross players do get are two kinds of compensation: fixed and contingent. The fixed part is the up-front money that gross players are paid whatever happens to the movie. The contingent part is the percentage of a pool—called the “distributor’s adjusted gross” in Hollywood lawyer lingo—that the players get after certain conditions are met, such as the movie earning back the amount of fixed compensation or reaching a contractually-defined cash breakeven point. The pool is “filled” with the money that the distribution arm collects or, in the case of DVDs, gets credited with. With movies, the pool (eventually) gets the remittance from theaters left over after the theater owners deduct their share of ticketsales and house allowance and after the distributor deducts off the top expenses, such as check collection, currency transfers, stamp taxes, duties, and trade association fees.

To see how these gross participations work in practice, look again at Arnold Schwarzenegger’s thirty-three-page contract for

Terminator

3, which is still considered the gold standard for the

super-gross players. For his fixed compensation, Schwarzenegger received $29.25 million—then a record sum. He got the first $3 million on signing and the balance during the course of principal photography. His contingent compensation was 20 percent of the adjusted gross receipts of the distributors (Warner Bros. in the US, Sony Pictures, and Intermedia abroad). The adjusted part of the equation allowed the studio to deduct the items specified on page three of the contract: All industry-standard and customary off-the-top exclusions and deductions, i.e. checking, collection conversion costs, quota costs, trade association fees, residuals, and taxes. Schwarzenegger’s lawyer Jacob Bloom is without peer in the entertainment business, but the best he could do here was to cap some of the collection charges at $250,000; he could not touch the residuals or tax deduction. Bloom did manage to get the all-important DVD royalty contribution to the pool raised to 35 percent (although only for Schwarzenegger). As good as this was, it meant that Schwarzenegger was entitled to only 7 percent of what the studios took in from their DVD sales.

Schwarzenegger’s contingent compensation would not kick in until the film met the breakeven point defined in the contract. Although the film achieved a $428 million world box office gross, it just barely reached its cash breakeven point, so,

alas, Governor Schwarzenegger has earned only a pittance so far from his gross participation beyond his $29.25 million payday. Tom Cruise got a more immediate slice of the action for

Mission Impossible 2

. In return for his producing, acting, guaranteeing against cost overruns, and paying other gross players their share—including Director John Woo’s 7.5 percent—Cruise’s production company got 30 percent of Paramount’s adjusted gross receipts.

In this light, Peter Jackson’s compensation for

King Kong

was a relative bargain. Universal paid $20 million in fixed compensation to Jackson’s production company not only for his directing services, but also for the script writing and producing services of his collaborators Fran Walsh and Philippa Boyens. And, making a sweet deal even sweeter, the New Zealand citizenship of Jackson and his team qualified Universal for a cash subsidy from the New Zealand government that could be as high as $20 million (and, by itself, that subsidy could pay Jackson’s entire fixed compensation). In addition, once the fixed compensation is earned back, Jackson’s company also got 20 percent of Universal’s adjusted gross receipts, which means it got at least an additional $20 million from movie rentals (which now have passed $200 million worldwide) as well as a huge payoff from future DVDs and television rights.

Such deals are costly, but not crazy. The studios’ business nowadays is entirely driven by huge franchises that serve as worldwide licensing platforms. And the most predictable rainmakers for these windfalls, such as Steven Spielberg, George Lucas, Tom Cruise, Jerry Bruckenheimer, and Peter Jackson, are all gross players represented by savvy lawyers and agents who know all the ropes of the movie business. To be sure, not all of their projects turn out to be billion-dollar franchises, but they have little downside. Look at

King Kong:

The upside for Universal was a licensing franchise that would enrich the studio with billions in revenues for years to come. But even if that gamble fails and there are no ape sequels, the studio will lose little, if any money, on the movie itself. In this topsy-turvy world, it makes perfect sense for the studios to recruit the best gross players, as long as the gross they give away is not really the gross.

Nowhere does Hollywood’s culture of deception more clearly manifest itself than on those television talk shows in which stars talk about their movies. The point of this media exercise, at least for the studios releasing the movies, is to fuse

the celebrity stars with their fictive movie characters (otherwise the stars might focus interest on themselves instead of the movies being opened). So carefully-designed PR scripts require that the stars “stay in character,” as Hollywood calls real life play-acting. When it comes to action movies, the scenario typically calls for stars to tell making-of-movie anecdotes that suggest that they, like the heroes they play on screen, perform death-defying feats. Even if the putative perils are an obvious stretch, they can almost invariably count on a suspension of disbelief on the part of their host-interrogator. Consider, for example, the heroics related on MTV by the three lovely stars of

Charlie’s Angels: Full Throttle

, Lucy Liu, Drew Barrymore, and Cameron Diaz. The MTV interviewer, JC Chasez began by asking, “Did you guys do any of your own stunts?”

“We did,” Lucy Liu (“Alex”) jumps in.

“We get to do all these amazing things,” Cameron Diaz (“Natalie”) adds, describing by way of example how Drew Barrymore (“Dylan”) clung to a speeding car going about “35 miles an hour” while “hitting on the hood of the car”—even after her safety cord came undone. “She’s literally hanging on to the car,” Liu explains.

At this point in the story, with Barrymore precariously holding onto the hood with one hand

and banging on it with the other, the interviewer asks her excitedly why she didn’t yell, “Cut”?

Barrymore (“Dylan”) explains despite the danger to herself, she persevered with the shot because “you get so into the adrenaline and you want to be tough. … my character, Dylan, was trying to stop the bad guy.” In other words, she had morphed into Dylan—at least in the PR script.

Now back to reality. Stars may have license on talk shows to fantasize about performing perilous stunts such as hanging off the hood of a speeding car, but on a movie set, no matter how willing they may be to risk their lives and limbs, studios will not permit them to take such risks for two reasons.

First, stars often do not have an opportunity to perform stunts because action movies are not shot linearly. The filming is divided between a first unit, “principal photography,” that shoots the stars and other actors, and the “second units,” which shoot the stunts as well as backgrounds that do not require the presence of the actors. In the James Bond movie

Tomorrow Never Dies

, for instance, this division of labor had five different people playing the James Bond character: Pierce Brosnan, the star, was playing James Bond at the Frogmore Studio outside of London, while four stuntmen at four different locations were playing him in stunts. Similarly, in

Charlie’s Angels: Full Throttle

, the “Dylan”

character, was played by Drew Barrymore and stuntwomen Heidi Moneymaker, a star gymnast, and Gloria O’Brien. (Lucy Liu’s character had four stunt players.)

A second, and even more compelling reason, is the cast insurance requisites. Even if stars are physically present during the shooting of perilous stunts, the production’s insurers prohibit them from substituting for the stuntmen. Since Harold Lloyd nearly lost two fingers performing his own stunts in 1920, cast insurance has been an absolute requisite for a Hollywood movie. If a star is deemed an essential element in a movie—as Liu, Diaz, and Barrymore are in

Charlie’s Angels: Full Throttle

—and the star becomes disabled, the insurer must cover the resulting loss, which in the case of

Charlie’s Angel: Full Throttle

was about $120 million. Before issuing such expensive policies, and no Hollywood movie could be made without one, insurers go to great lengths to make sure that actors do not take any risks that could lead to even a sprained ankle or pulled muscle. Their representatives analyze every shot in the script for potential risks and scrutinize the stars’ prior behavior on and off the screen. Once the production starts, they also station hawk-eyed agents on the set to make sure that the stars are not put in harm’s way. They might require, for example, that a star standing

on a stationary car be held by two safety men (masked in blue spandex so they can be digitally deleted from the final movie). Even if a director or producer were willing to risk injuring a star, the insurer would not allow it. So stars, as much as they might enjoy performing their fantasies, cannot do dangerous stunts for movies.

For the most part, stars do not tell these tall tales of daredevilism on television out of either personal dishonesty, vanity, or egoism. It is their job to play a character in publicity appearances, just as it is the job of studios to hype their movies. Nor do others in these Hollywood productions, even if they were not bound by contractual restrictions on disclosures, or “NDAs,” have reason to demystify such off-screen fictionalizing. The subterfuge is part of the system by which studios, talent agencies, music publishers, licensees, and others create, maintain, and profitably exploit the stars’ public personalities. The more interesting question: why entertainment journalists, instead of challenging these preposterous claims, act as the stars’ smiling attendants on this organized flight from reality? The answer: deception is a cooperative enterprise. By suspending their disbelief, the entertainment journalists get the stars on their programs.

MACHINE

LARA CROFT: TOMB RAIDER

IS CONSIDERED A MASTERPIECE OF STUDIO FINANCING

A Hollywood studio has both an official budget, which is often leaked to trade papers such as

Variety

and

The Hollywood Reporter

, to show how much money it is supposedly costing to produce, and a closely-held production cost budget that shows how much money the movie is actually costing to

produce. The latter budget, which is rarely seen by anyone outside of a studio, takes into account the money the studio gets from government subsidies, tax shelter deals, product placement, and other sources that greatly offset the amount of its own money that a studio actually has to sink into a film. A vice president at Paramount explained to me how these invisible maneuvers, including pre-sales abroad, can reduce the risk to practically zero. As an example, he cited Paramount’s

Lara Croft: Tomb Raider

as a “minor masterpiece” in the arcane art of studio financing. Although the official budget for this 2001 production was $94 million and reported even higher in the press, the studio’s outlay was only $8.7 million. How?

First, Paramount got $65 million from Intermedia Films in Germany in exchange for distribution rights to

Lara Croft: Tomb Raider

for six countries: Britain, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and Japan. These “pre-sales” left Paramount with the rights to market its film to the rest of the world.