The History of Love (17 page)

Read The History of Love Online

Authors: Nicole Krauss

2.

HE GAVE ME A PEN THAT COULD WORK WITHOUT GRAVITY

“It can work without gravity,” my father said, as I examined it in its velvet box with the NASA insignia. It was my seventh birthday. He was lying in a hospital bed wearing a hat because he had no hair. Shiny wrapping paper lay crumpled on his blanket. He held my hand and told me a story about when he was six and threw a rock at a kid’s head who was bullying his brother, and how after that no one had ever bothered either of them again. “You have to stick up for yourself,” he told me. “But it’s bad to throw rocks,” I said. “I know,” he said. “You’re smarter than me. You’ll find something better than rocks.” When the nurse came, I went to look out the window. The 59th Street Bridge shone in the dark. I counted the boats passing on the river. When I got bored, I went to look at the old man whose bed was on the other side of the curtain. He slept most of the time, and when he was awake his hands shook. I showed him the pen. I told him that it could work without gravity, but he didn’t understand. I tried to explain again, but he was still confused. Finally I said, “It’s to use when I’m in outer space.” He nodded and closed his eyes.

3. THE MAN WHO COULDN’T ESCAPE GRAVITY

Then my father died, and I put the pen away in a drawer. Years passed, and then I was eleven and got a Russian pen pal. It was arranged through our Hebrew School by the local chapter of Hadassah. At first we were supposed to write to Russian Jews who had just immigrated to Israel, but when that fell through we were assigned regular Russian Jews. On Sukkot we sent our pen pals’ class an etrog

with our first letters. Mine was named Tatiana. She lived in St. Petersburg, near the Field of Mars. I liked to pretend she lived in outer space. Tatiana’s English wasn’t very good, and often I couldn’t understand her letters. But I waited for them eagerly.

Father is mathematician,

she wrote.

My father could survive in the wild

, I wrote back. For every one of her letters, I wrote two.

Do you have a dog? How many people use your bathroom?

Do you own anything that belonged to the Czar?

One day a letter came. She wanted to know if I had ever been to Sears Roebuck. At the end there was a p.s. It said:

Boy in my class is moved to New York

.

Maybe you want write him because he knows anybody.

That was the last I ever heard from her.

4.

I SEARCHED OUT OTHER FORMS OF LIFE

“Where’s Brighton Beach?” I asked. “In England,” my mother said, searching the kitchen cabinets for something she’d misplaced. “I mean the one in New York.” “Near Coney Island, I think.” “How far is Coney Island?” “Maybe half an hour.” “Driving or walking?” “You can take the subway.” “How many stops?” “I don’t know. Why are you so interested in Brighton Beach?” “I have a friend there. His name is Misha and he’s Russian,” I said with admiration. “Just Russian?” my mother asked from inside the cabinet under the kitchen sink. “What do you mean,

just

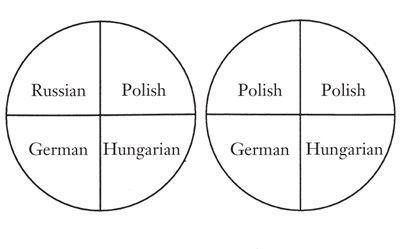

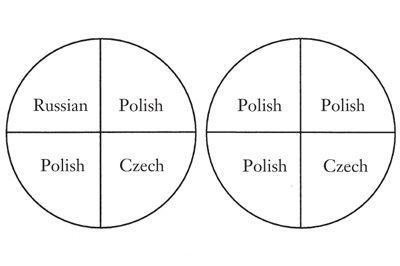

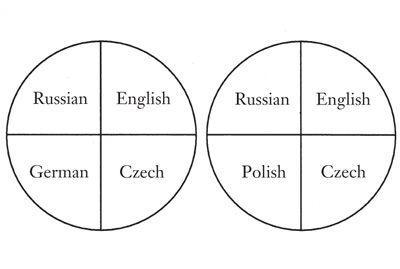

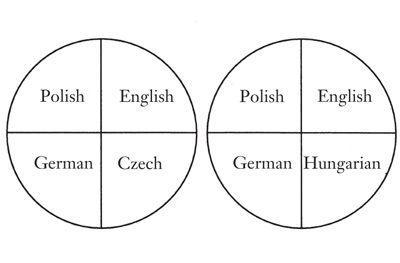

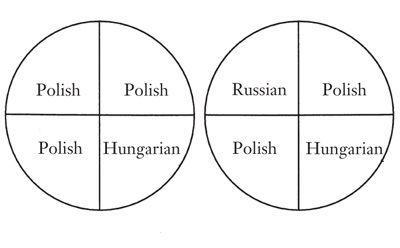

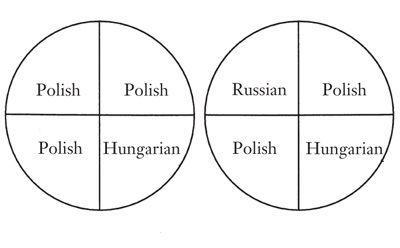

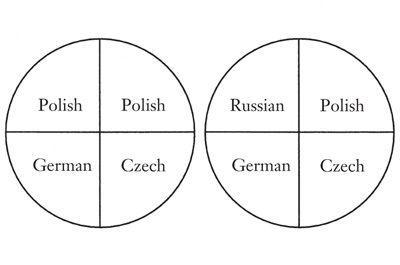

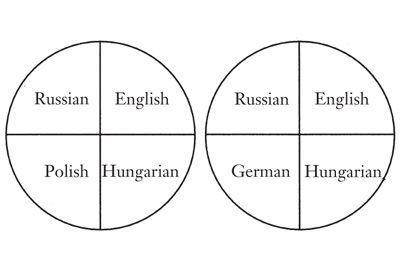

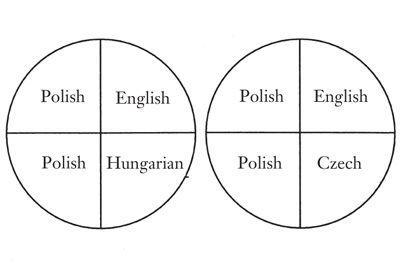

Russian?” She stood up and turned to me. “Nothing,” she said, looking at me with the expression she sometimes gets when she’s just thought of something amazingly fascinating. “It’s just that you, for example, are one-quarter Russian, one-quarter Hungarian, one-quarter Polish, and one-quarter German.” I didn’t say anything. She opened a drawer, then closed it. “Actually,” she said, “you could say you’re three-quarters Polish and one-quarter Hungarian, since Bubbe’s parents were from Poland before they moved to Nuremberg, and Grandma Sasha’s town was originally in Belarus, or White Russia, before it became part of Poland.” She opened another cabinet stuffed with plastic bags and started rooting around in it. I turned to go. “Now that I’m thinking about it,” she said, “I suppose you could also say you’re three-quarters Polish and one-quarter Czech, because the town Zeyde came from was in Hungary before 1918, and in Czechoslavakia after, although the Hungarians continued to consider themselves Hungarian, and briefly even became Hungarian again during the Second World War. Of course, you could always just say you’re half Polish, one-quarter Hungarian, and one-quarter English, since Grandpa Simon left Poland and moved to London when he was nine.” She grabbed a piece of paper from the pad by the telephone and started to write vigorously. A minute passed while she scratched away at the page. “Look!” she said, pushing the paper over so I could see it. “You can actually make

sixteen

different

pie charts, each of them accurate!” I looked at the paper. It said:

“Then again, you could always just stick with half English and half Israeli, since—” “I’M AMERICAN!” I shouted. My mother blinked. “Suit yourself,” she said, and went to put the kettle on to boil. From the corner of the room where he was looking at the pictures in a magazine, Bird muttered: “No, you’re not. You’re Jewish.”

5.

ONCE I USED THE PEN TO WRITE TO MY FATHER

We were in Jerusalem for my Bat Mitzvah. My mother wanted to have it at the Wailing Wall so Bubbe and Zeyde, my father’s parents, could attend. When Zeyde came to Palestine in 1938 he said he wasn’t ever going to leave, and he never did. Anyone who wanted to see him had to come to their apartment in the tall building in Kiryat Wolfson, overlooking the Knesset. It was filled with the old dark furniture and old dark photographs they’d brought from Europe. In the afternoon they lowered the metal blinds to protect it all from the blinding light, because nothing they owned was made to survive in that weather.