The History of Florida (95 page)

Read The History of Florida Online

Authors: Michael Gannon

Tags: #History, #United States, #State & Local, #Americas

Supreme Court of Florida only to see the ruling negated within a matter of

months.

The march of Jim Crow took place within the context of sometimes-vi-

olent subjugation of Florida’s African American population, especial y, but

not always, in places remote from the larger cities. During the half century

that began in 1880, Florida led in the nation in lynchings when computed on

a per capita basis. The span of years from 1900 to 1917 alone saw about ninety

black men put to death, often horribly, by extralegal violence. The supposed

wrong might be as simple as an inadvertent insult to a white woman. Fifty

more lynchings from 1918 to 1930 inflated the total. In fact, from 1900 to

1930 Florida’s lynching rate ran nearly twice as high as that of Mississippi,

Georgia, or Louisiana; more than three times that of Alabama; and six times

that of South Carolina. The carnage did not end there. The nation watched

aghast in 1934 at the travesty of justice involved in the cruel Jackson County

murder of Claude Neal. One year later, Ku Klux Klansmen had dragged

Reuben Stacy from a Fort Lauderdale jail before putting him to death by

hanging and gunfire, while Tal ahassee lawmen acting as Klansmen lynched

Richard Hawkins and Ernest Ponder in 1937 virtual y at Supreme Court

Justice Glenn Terrel ’s front door. As late as 1945 Governor Mil ard Caldwell

454 · Larry Eugene Rivers

simply refused to investigate the lynching of Jesse James Payne in Madison

County, creating another national scandal. In justification of his failure to

act, the governor merely denied there had been a lynching.

The early 1910s brought dramatic change and not for the best. Florida’s

progressively evolving urban-oriented black culture and society col ided

with a rising tide of Jim Crow discrimination, racial violence, and eco-

nomic intimidation. Adding to the problems were increasingly depressed

conditions in rural areas produced by the cotton boll weevil and low cotton

prices, a situation from which those who “sharecropped” and did not own

their land suffered the most. Booker T. Washington’s 1912 tour of the Sun-

shine State exemplified the transitory nature of the times. At Lake City, the

famed educator credibly could assert, “In every community in the South

where colored people live in large numbers there are white friends who

stand by us.” Then, days later at Jacksonville, Washington recoiled as a white

mob unsuccessful y attempted to seize him from his automobile. Historian

David H. Jackson Jr. described events occurring thereafter. “In the midst of

his speech, Washington heard the howls of a mob in the distance on its way

to lynch the accused murderers of [white grocer Simon] Silverstein at the

jail,” the historian wrote. To his credit, according to Jackson, Washington

“launched into a fervid denunciation of lynching and ended with an earnest

proof

and eloquent appeal for better feeling between the races.”8

In the years surrounding Booker T. Washington’s close escape at Jackson-

ville, a tide shifted within Florida’s African American population and, with

the shift, large numbers of men, women, and children opted to abandon

their Sunshine State homes for an uncertain future in the North. The “Great

Migration” touched all of the Deep South states of the former Confederacy,

but in Florida the impact evidenced itself unmistakably. A report detailed

the net loss as of 1916. Live Oak had had seen “a large proportion of its col-

ored population” depart, as had Dunnellon. One-third of black Lakelanders

had left. “Not less than one-fourth of the black population of Orlando was

swept into this movement,” the report continued. “Probably half of the ne-

groes of Palatka, Miami and DeLand, migrated as indicated by schools and

churches, the membership of which decreased one-half.” It added: “From

3,000 to 5,000 negroes migrated from Tampa and Hil sboro County. Jack-

sonville, the largest city in Florida, with a population of about 35,000 ne-

groes, lost about 6,000 or 8,000 of its own black population and served as

an assembling point for 14,000 or 15,000 others who went to the North.”9

The emigration tide continued its urgent flow as another racist governor,

Sidney J. Catts, took office in 1917. Known as “the Cracker Messiah,” Catts’s

Florida’s African American Experience: The Twentieth Century and Beyond · 455

views ran to such extremes that he opposed, as his biographer Wayne Flynt

put it, “both vocational and classical education for Negroes.” The gover-

nor at first seemed pleased as black traveling parties crossed the state line

headed north, but America’s entry into World War I placed demands upon

the state that a weakened labor pool could not begin to meet. Now, Catts

delved into his experience as a Baptist preacher to urge African Americans,

as Flynt noted, “to stay in a warm climate where ‘the Creator had put them.’”

When that overture proved of no avail, the state’s chief executive launched a

roundup of northern labor recruiters while prompting local governments to

issue “work or fight” orders designed to compel black men to seek employ-

ment or be drafted into the military. In the end, laborers from the Bahamas

filled the gap that Catts’s misguided leadership could not.10

Long-term consequences, it hardly need be said, resulted from the flight

of so many. To begin with, a significant percentage of the most talented and

promising black Floridians departed, some for good, some fortunately only

temporarily. James Weldon Johnson—who at Jacksonville in 1900 had au-

thored the words to “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” often called the Negro na-

tional anthem—already had gone, as had his composer brother Rosamond,

a graduate of the New England Conservatory and the artist who added the

music to “Lift Every Voice and Sing.” Large enough numbers followed that

proof

Florida’s contributions to what history has called the Harlem Renaissance

of the 1920s and 1930s stood extraordinarily high. To name only a few in-

dividuals, James Weldon Johnson earned respect as a writer and poet while

Zora Neale Hurston of Eatonvil e penned evocative fiction and insightful

sociological studies focused back on her home state. Poet Alpheus Butler,

son of Miami’s first black medical doctor, James A. Butler, launched a cre-

ative career that flourished for four decades. Sculptor Augusta Savage of

Green Cove Springs meanwhile developed talent of immense proportions.

It is easily understandable why, in 1934, she would become the first Afri-

can American selected to the National Association of Women Painters and

Sculptors.

Along with the writers, poets, artists, sculptors, and intel ectuals unfortu-

nately went some of the greatest leadership potential. Florida’s loss happily

proved the nation’s gain. If any one person embodied this fact, that person

was Crescent City’s A. Philip Randolph. Organizer of the Brotherhood of

Sleeping Car Porters, he had emerged by the 1940s as one of the nation’s

most powerful labor leaders. Stil active decades later, Randolph can be

credited with organizing the 1963 March on Washington, the largest civil

rights demonstration ever held in the United States.

456 · Larry Eugene Rivers

proof

Zora Neale Hurston left the all-black town of Eatonville, near Orlando, where she was

born, to pursue an education and a writing career in New York City. With books such as

Mules

and

Men

(1935),

Their

Eyes

Were

Watching

God

(1937), and

Dust

Tracks

on

a

Road

(1942), she became a luminary of the Harlem Renaissance group of writers and drama-tists in 1930s. Though her last years were spent in poverty as a domestic servant in Fort

Pierce, where she was buried in an unmarked grave in 1960, her name and books have

since achieved international fame.

The Great Migration, when combined with growth in central and south

Florida during the 1920s and afterward, additional y accelerated key de-

mographic and economic trends. Black residents of rural areas, especial y

young people, increasingly sought lives in towns and cities, whether north-

ern or in Florida. Unprepared by education or experience for the new en-

vironment, the arrivals often found it difficult, if not impossible, to secure

rewarding or even dependable employment. Florida’s economic “bust” of

Florida’s African American Experience: The Twentieth Century and Beyond · 457

1926, which ushered in Depression-era conditions that, in places, would en-

dure until World War II, made matters even worse. Urban poverty and asso-

ciated problems grew as black contributions to Florida agriculture declined.

Low commodity prices pressed African American owners and devastated

sharecroppers. White-dominated state and local governments meanwhile

permitted white owners to pay extraordinarily low wages while al owing im-

portation of competing foreign workers. A 1963 report detailed the results.

“The living and working conditions of the Negro farm worker in the State

of Florida have already deteriorated far beyond the minimal standards of

decency that are normal y accepted in American society.”11

The most urban of southern states in the process became even more ur-

ban as each year and decade of the twentieth century passed by. The state’s

population, including its African American population, grew by leaps and

bounds after 1920. Always, though, whites arrived in far higher numbers

proof

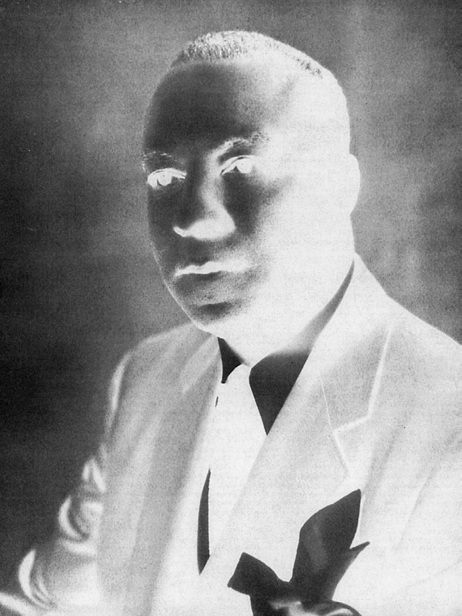

A. Philip Randolph was born in Crescent City in 1889. Educated in Jacksonville and New

York in the 1920s, he organized the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, an all-black

AFL union. As a result of his leadership, Pullman porters’ working hours were cut, pay

was increased, and working conditions were improved. During World War II and after-

ward, Randolph worked to end racial discrimination in defense factories and in the

military. In 1963 he organized and directed a march on Washington that became the

largest civil rights demonstration in the nation’s history. He died in 1979.

458 · Larry Eugene Rivers

than did blacks. Having constituted almost 44 percent of Florida’s popula-

tion in 1900, by World War II’s end in 1945 the African American total stood

at less than 25 percent. The slide continued to the point that blacks of non-

Hispanic origin comprised by 2010 a slim 16 percent of 18.8 million persons.

That low figure interestingly represented an uptick from 2000’s 14.6 percent.

Where a dozen counties had shown African American majorities in 1900,

only two—Gadsden and Jefferson—did so in 1945. Gadsden alone claimed

a black majority in 2010. Black majorities in high-population cities, too, had

disappeared well before World War II’s conclusion. Florida’s demographic

face had been altered irrevocably.

Back during the World War I era, when these trends were beginning to

build, black residents remaining in Florida faced a serious and immediate

challenge of protecting themselves against prevailing threats. Accordingly,

protective leagues of various sorts were organized local y and groups such

as the Odd Fellows and the Knights of Pythias attempted as best they could

to afford statewide connections. Black lawyers—among them I. H. Purcel ,