The History of Florida (70 page)

Read The History of Florida Online

Authors: Michael Gannon

Tags: #History, #United States, #State & Local, #Americas

hotels, including the Biltmore in Coral Gables. The Hol ywood Beach Hotel

became a naval training school, the Breakers in Palm Beach saw service

as an army hospital, and the rustic Everglades Rod and Gun Club hosted

the Coast Guard during the war. Dan Moody’s experience must have been

repeated many times. The young Virginian arrived at Miami Beach on 29

January 1944, and dutiful y wrote his parents on Hotel Blackstone station-

ary: “Mother, this is the most beautiful place that I have ever seen. . . . I real y

think when the war is over, I’ll move down here.”3

The Sunshine State became the Garrison State. In Fort Pierce, 150,000

men passed through the Naval Amphibious Training Base, home of fu-

ture frogmen and underwater demolition experts. Along the Big Bend,

at Camp Gordon Johnston in Carrabel e, thousands of soldiers perfected

World War II · 335

future invasion tactics that would be employed on beaches in North Africa,

Normandy, and Tarawa. Daytona Beach managed a WAC (Women’s Army

Corps) base as a result of Mary McLeod Bethune’s lobbying of Eleanor

Roosevelt.

Wings over Florida became a familiar sight. In 1939, Florida boasted

six aviation schools; by the end of the war, the state claimed forty aviation

instal ations. Residents became accustomed to the distinctive sounds and

silhouettes of Navy Hel cats, B-17 Flying Fortresses, and TBM Avengers.

Airfields offered specialized training. Pilots at the Lake City and Sanford

naval air stations perfected dive bombing.

Although the count is imprecise, as many as 2 million military recruits

spent some time in Florida from 1941 to 1945. George Herbert Walker Bush

learned to fly torpedo bombers at the Fort Lauderdale Naval Air Station.

Ted Wil iams served as a flight instructor at the Pensacola Naval Air Station.

George C. Wal ace trained as a flight engineer in Miami while Paul Newman

completed radio school and gunnery training in Jacksonvil e and Miami.

Andy Rooney spent time at Camp Blanding, where he wrote for

Stars

and

Stripes.

Already an accomplished artist, Jacob Lawrence was stationed in St.

Augustine, where he served in the Coast Guard. His lodging consisted of a

room formerly assigned to kitchen help in the Ponce de Leon Hotel. Clark

proof

Gable endured basic training at Miami Beach and excelled at the Flexible

Gunnery School at Tyndall Field in Panama City.

Floridians escaped to the Dixie Theatre in Apalachicola or the Athens

in DeLand to watch war movies filmed in Florida:

Air

Force,

A

Guy

Named

Joe

, and

They

Were

Expendable.

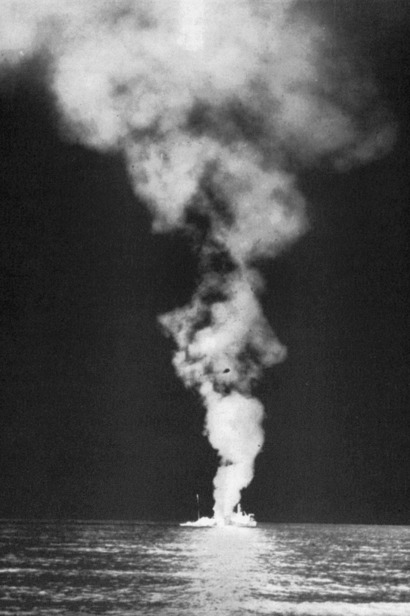

But Floridians living along the east coast

watched the real war come to them. German submarines seized a strategic

opportunity in January 1942, launching Operation Drumbeat. German U-

boats sank twenty-four ships off Florida’s coasts. Residents and tourists at

Jacksonville Beach and Cocoa Beach, among others, watched in horror as

tankers burned and thick oil coated the white sand. Hundreds of lives were

lost, along with critical cargo and resources, until the Allies developed an

effective convoy system and perfected the use of sonar. Volunteers softened

the human tragedy.

Miami

Herald

columnist Helen Muir wrote a story of a

young nurse wiping tar off a bedraggled merchant mariner, asking him, “Is

this your first visit to Florida?”4

Floridians welcomed the sight of men and women in uniform. But Ger-

man prisoners of war evoked suspicion and fear. Of the 372,000 German

POWs incarcerated in the United States, almost 12,000 spent time in Flor-

ida. They picked oranges in Dade City, Leesburg, and Winter Haven, cut

336 · Gary R. Mormino

sugarcane in Clewiston, and swept the streets of Miami Beach. The largest

group was stationed at Camp Blanding. In one of the war’s more ironic mo-

ments, German POWs picked cotton at El Destino, one of Jefferson Coun-

ty’s great antebel um plantations.5

World War II, not the New Deal, ended the Great Depression and un-

leashed one of the greatest economic booms in American history. From

1940 to 1945, federal expenditures soared from $9 billion to $98.4 billion.

National y, per capita income doubled during the war, while personal sav-

ings increased tenfold and the labor force expanded by 9 million workers—

all during a two-front war that absorbed 16 American million soldiers. The

war wrought extraordinary changes to two neglected regions—the Ameri-

can West and South. The South, often a subject of derision and pity, and

once identified by President Roosevelt as the “Nation’s No. 1 economic prob-

lem,” was swept into the vortex of prosperity and change.

Fortune

magazine

translated the heady events into understandable terms: “For the first time

since the War Between the States, almost any native of the Deep South who

wants a job can get one.”6 The war funneled huge sums of money into Flor-

ida’s underdeveloped economy that had rested for decades upon an uneasy

tripod of tourism, extractive industries, and agriculture. Statistics reveal the

dramatic impact. War contracts revived the state’s slumbering agricultural

proof

and manufacturing sectors. The war also rejuvenated Florida’s moribund

shipbuilding industry.

In 1940, Bay County languished in poverty, an isolated wedge supporting

20,000 residents along the state’s Big Bend. The county boomed as the result

of Tyndall Field and government contracts. The population trebled by 1945.

The Wainwright Company constructed 108 vessels during the war, including

102 Liberty ships. At its peak, the Panama City shipyards employed 15,000

workers, earning premium wages. The general contractor, J. A. Jones, as-

sumed the role of urban planner and city boss, building homes for workers

and delivering milk and ice to families.

Defense buoyed Tampa, a city reeling since the Great Depression had

devastated the once-vaunted cigar industry. The construction of MacDill

and Drew Air Fields and the reconstruction of a shipbuilding industry

spel ed a new prosperity. The Tampa Shipbuilding Company employed

9,000 workers by 1942 and desperately searched for new laborers, a problem

exacerbated with the establishment of a second major shipyard at Hooker’s

Point. The shipyards paid union wages; skilled workers averaged $1.03 an

hour, with unlimited overtime. The companies sponsored athletic teams,

published newspapers, and even provided alarm clocks for workers.7

proof

Twenty-four U.S. and Allied freighters and tankers were sunk in Florida coastal

waters by German submarines (U-boats) during World War II, particularly during

the period February–July 1942. Many torpedoed merchant vessels could be seen

burning from the front porches of beach houses and from the balconies of tourist

hotels. Here a stricken tanker burns off Hobe Sound.

338 · Gary R. Mormino

The war’s cornucopia also enriched the economies of Pensacola, Jack-

sonvil e, and Miami. The Pensacola Shipyard and Engineering Company

employed 7,000 workers; in addition, the government spent $55 mil ion

expanding the Pensacola Naval Air Station and constructing auxiliary fields.

Jacksonville’s docks bustled. Local firms built 82 Liberty ships and scores of

minesweepers and PT (patrol torpedo) boats. The city also served as head-

quarters for the Naval Overhaul and Repair facility. In Miami, vessels from

the Caribbean and South America thronged the Miami River docks. Mi-

ami’s economy surged from streams of military recruits, defense contracts,

and, improbably, tourist spending. The home of Eastern Airlines and Pan

American Airlines, Miami solidified its hold as the most important hub for

South American flights.

The parade of industrial statistics might lead one to believe that the Sun-

shine State had transformed its economy into an arsenal. For al the new and

revived industries, the state’s economic standing changed little during the

war; indeed, one can argue that Florida actual y slipped in sectors critical to

postwar growth. And once the war ended, the bustling shipyards largely dis-

appeared. Moreover, in industries critical to sustained growth—chemicals,

oil refining, iron and steel foundries, aircraft manufacturing, electronics,

automobiles—Florida cities fared poorly, even when compared to southern

proof

rivals Atlanta, Mobile, Norfolk, Galveston, and Houston.

Agriculture achieved dramatic gains during the war, realizing new prof-

its and incorporating new technologies. Southern farmers in general, and

Florida in particular, had endured two lean decades since the flush times

of World War I. But World War II brought good times back. North Florida

cotton planters prospered with the rise of cotton prices from 10 cents to 22

cents per pound between 1939 and 1945.

Grove owners harvested orange gold during the war. Notable milestones

in the marketing and processing of citrus occurred. Florida’s citrus harvest

surpassed California’s for the first time in 1942–43, producing 80 mil ion

boxes of oranges and grapefruit. That year’s yield also marked Florida’s first

$100 million crop. Scientists helped solve a problem long vexing the indus-

try: waste and spoilage. Chemists at the Florida Citrus Commission pat-

ented a process to make frozen concentrated orange juice. Few realized the

significance of the development, because in 1944, few American homes or

stores had freezers. But frozen concentrate revolutionized the citrus indus-

try and the consumption of juice after the war.

The war also wrought a green revolution. While researchers at the Bureau

of Entomology in Orlando advanced the frontiers of jungle warfare, they

World War II · 339

discovered an insecticide with revolutionary implications. By 1945, DDT

was available for commercial use, promising an end to a tropical Florida

teeming with palmetto bugs, cattle ticks, and voracious mosquitoes.

Time

magazine, however, cautioned against careless optimism: “Not much is

known as yet about the full effect of DDT on large areas.”8 Undeterred, Flo-

ridians rushed to saturate the new witch’s brew on swamps and backlots.

Not until 1962 with the publication of Rachel Carson’s seminal book

Silent

Spring

would they learn how damaging pesticides were, particularly DDT,

to the environment.

The war’s new technologies augured a bright future for grove owners and

planters, but scientists had yet to invent machines to pick oranges and cut

sugarcane. A drastic labor shortage confronted farmers. Historical y, Af-

rican Americans had performed low-paid agricultural work. But the once

reliable and pliable workforce disintegrated, as blacks enlisted in the service

or accepted better-paying positions in northern industries or Florida cities.

Florida confronted a labor crisis as experts predicted a shortage of 10,000

pickers for the 1943–44 citrus season. Across Florida, cities and officials

passed new vagrancy laws or enforced old ones, determined to punish slack-

ers and obtain seasonal laborers. Governor Spessard Hol and and many mu-

nicipalities promulgated “Work or Fight” laws. In Clearwater, charged the

proof

Tampa

Morning

Tribune,

“The city has put more than fifty chronic loafers,

including some gigolos, to work. . . . Many were Negroes who borrowed

money from their girlfriends to aid their loafing.”9 In Apopka, officials cit-

ing vagrancy laws arrested scores of African Americans, assigning them

to labor in the celery fields. In 1945, Governor Mil ard Caldwel ordered

Florida sheriffs to eliminate indolence. The sheriff of Martin County openly

admitted that his office would cooperate with farmers, sawmill operators,

and others doing essential work in seeing they received al the help they

needed.

Nowhere was the line between freedom and bondage more blurred than

on the vast sugar plantations of south Florida. Historical y, the cane fields at-

tracted the most desperate workers. When the war began, the United States