The History of Florida (7 page)

Read The History of Florida Online

Authors: Michael Gannon

Tags: #History, #United States, #State & Local, #Americas

Little Manatee River. A cavalry patrol from that site into the interior flushed

out a Spanish survivor of an expedition sent from Cuba eleven years ear-

lier to discover, if possible, what had happened to Pánfilo de Narváez. Juan

Ortíz by name, he had lived as a tribal native in the region for years. Now his

providential rescue provided de Soto with an interpreter who spoke indig-

enous tongues and Spanish, but as the army encountered different linguistic

groups on its march, his facility as a translator and as a geographer would

diminish.

The march into the interior began on 15 July. Mindful of Narváez’s fateful

error, de Soto left all his supplies on board four ships in the harbor, guarded

by forty cavalry and sixty infantry, with firm orders not to sail until he sent

men to guide the vessels to a precisely known anchorage to the north. The

First European Contacts · 29

long overland procession of people, horses, mules, and long-legged Spanish

range pigs then entered the vastness of Florida’s forests, rivers, bogs, and

sandhil s. The last feature was discovered just three days into the march, in

the vicinity of Zephyrhil s and Lumberton, where one man died of thirst

and others barely survived the absence of springs, streams, or standing wa-

ter. The next day, near Dade City, the army found its first cornfields. Though

he had crossed a smaller river, the Alafia, by constructing a bridge, and had

successful y though painful y negotiated the wetlands of the Cove of the

Withlacoochee in eastern Citrus County, on 26 July de Soto met his first

serious test at the strong currents of the Withlacoochee River itself, not far

from Inverness. There the army stretched a rope from bank to bank and

managed to wade across, losing one horse to the currents.

On 29 July, the army found itself in the major Timucuan province of

Ocale, believed to have occupied what now is southwest Marion County.

Here and at the province of Acuera, north of Leesburg on or near the Ock-

lawaha River, the Spaniards commandeered the natives’ standing crops and

food stores. Then, leaving the main body of the army at Ocale, de Soto led

a reconnaissance force through Levy and Alachua Counties, passing on

Gainesville’s west side (the native Potano) and reaching the Santa Fe River,

which the advance party bridged on 17 August. Here the unity of the force

proof

was rent by disagreements of some kind, not recorded, but perhaps rising

out of plain frustration: the El Dorado of their dreams must never have

seemed less real than it did among the swamps and pines of Florida. The

soldiers named the river Santa Fe las Discordias, the River of Discords.

De Soto camped across the river at a moderately sized vil age named

Aguacaleyquen and dispatched eight horsemen to lead forward the main

body stil in Ocale. At Aguacaleyquen, abandoned by its inhabitants, de Soto

found their hidden maize stores. Later, he captured seventeen natives, seized

their chief, and held his daughter hostage. To this behavior may be added

other, worse, violations that characterized de Soto’s peregrinations through

the Florida chiefdoms, all of them in direct violation of the king’s ordinance

to observe “good treatment and conversion” of the natives: some natives he

summarily executed for offenses real or perceived; others he mutilated (e.g.,

cutting off noses or hands) as a warning of what would be done to all if he

was not granted free passage through a vil age or a province; stil others

he enslaved and shackled to serve the marching army as bearers. By such

actions he showed that he had not forgotten the intimidating and violent

approach to indigenous societies learned under Pedrárias in Panama and

Nicaragua. Ostensibly the actions were authorized by a formal theological

30 · Michael Gannon

proof

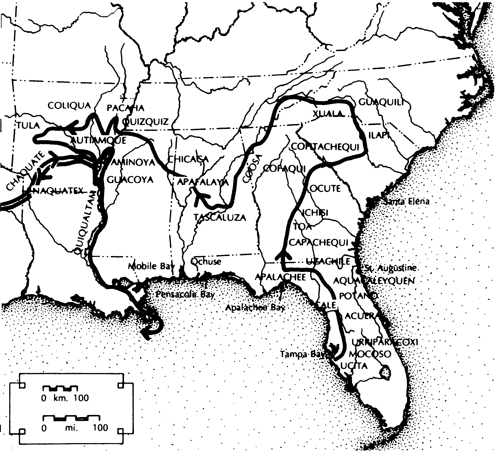

The route of Hernando de Soto’s expedition through La Florida, which at the time em-

braced the entire region shown here. Place-names along the march are the principal

native chiefdoms encountered. Also shown here are the future settlements of Tristán

de Luna (Ochuse) and of Pedro Menéndez de Avilés (St. Augustine and Santa Elena).

proclamation, the

Requirimiento

, which was read aloud in Spanish to the

uncomprehending natives. Some probable cultural explanations can be of-

fered for this harsh conduct. First, the Spanish captains’ actions to control

New World natives were to a large measure an extension of the Reconquista,

the struggle to regain control of Iberia from the Muslims, concluded in 1492.

A cult of military violence nourished over many centuries carried over into

the circum-Caribbean, of which Florida was a part. Second, Roman Catho-

lic theology in Spain was stil uncertain about the moral standing of the

native Americans, whose existence was not accounted for in holy scripture.

Were they ful y developed human beings with souls? Or were they a lower

species that might justifiably be exploited and enslaved? The question would

not be resolved in the natives’ favor until Carlos V’s promulgation of the so-

called New Laws in 1542, the year of de Soto’s death. It may be added that,

First European Contacts · 31

though de Soto’s entourage included twelve priests, none appears to have

had the vision and moral courage of Ayllón’s friar Montesinos where treat-

ment of the natives was concerned.

In their turn, the Florida natives gave back as good as they got, from

Tampa Bay, where the aborigines raked the army with cane arrows tipped

with fishbones, crab claws, or stone points, until de Soto’s withdrawal north-

ward into Georgia from Apalachee. All along the line of march, native ar-

chers, darting from woodland cover, killed Spanish dispatch riders or strag-

glers, set ambushes, or fired volleys into nighttime bivouacs. Brave native

hostage-guides cool y led the army into ambushes, though it meant certain

death for the hostage, probably at the jaws of war dogs. The Spaniards mar-

veled at the velocity and accuracy of the arrows discharged against them

by the natives’ tal , stiff bows. This would be particularly so in Apalachee,

where the projectiles were said to have penetrated horses lengthwise nearly

from chest to tail, and de Soto watched one captured archer place an arrow

through two coats of Milan chain steel from eighty feet back. The best de-

fense, the Spaniards eventual y learned, for their horses as well as for them-

selves, was to wear quilted fabric three or four fingers thick under the chain

mail.

From Tampa Bay through Apalachee, de Soto enjoyed only one stand-

proof

up fight in open country where the massed cavalry charge for which he

was equipped held the advantage. It took place at Napituca, near Live Oak,

in mid-September. Anticipating an ambush, de Soto stationed his cavalry

in woods surrounding two flooded limestone sinkholes and charged the

warriors of the district when they betrayed their intent. Many natives were

lanced in the field. Others threw themselves into the ponds where they

treaded water until exhausted. Eventual y captured, these and other natives

of the region later rose up against their captors, which caused de Soto to

execute all the mature warriors among them.

From Napituca the Spaniards traveled almost due west, seeking the prov-

ince of Apalachee, where Narváez’s men had found abundant crops. On 25

September they bridged the River of the Deer, as they named the Suwannee,

and six days later, they came to Agile, the first town that was subject to the

Apalachee. It was not until 3 October, when they made a difficult crossing of

the flooded Aucil a River, that they encountered the Apalachee proper. The

natives put up a fierce armed resistance and burned their crops and vil ages

as they drew back before the foreigners’ advance. Thirty-eight miles farther

west, on 6 October, de Soto entered Anhaica, the main town of Apalachee,

where he decided to make his winter camp. Near the coast on Apalachee

32 · Michael Gannon

Bay his men found the remains, including horse skul s, of Narváez’s camp of

eleven years before. With a known anchorage, de Soto sent a party of caval-

rymen south to lead forward the ships, supplies, and men left at Tampa Bay.

On 25 December the camp celebrated the first Christmas in what is now the

United States.

The Anhaica encampment site was discovered in 1987 by archaeologist

B. Calvin Jones, who, while excavating a short distance east of the Capitol

in Tal ahassee, turned up a pig mandible (de Soto had introduced the pig to

this country), an iron crossbow point, iron nails, chain mail still linked to-

gether, and dated copper coins. (In 2012 a landowner named Ashley White

in north Marion County unearthed on his property a pig mandible, chain

mail, medieval coins, and glass beads, all apparently lost earlier from uni-

form pockets or saddlebags along de Soto’s line of march.) The Spaniards’

stay at Anhaica was beset by almost constant gueril a warfare, with the result

that, by the date of their departure north into Georgia, on 3 March 1540, nu-

merous bones of man and horse alike remained behind under the Apalachee

sun.

It would be tedious to detail the remainder of the expedition outside

present-day Florida, which seems to the reader of the surviving chronicles

to be an aimless, feckless wandering in search of the same gold, silver, and

proof

gems that de Soto had found in Peru. No known attempt was made to map

the interior, to record flora and fauna, to understand the polities and cul-

tures of the native societies encountered, to evangelize, or to forge alliances.

Suffice it to say that the Spaniards marched northeast through Georgia into

South and North Carolina, turned west through a corner of Tennessee, then

south through the northwest corner of Georgia, finding plentiful corn and

game at Coosa (east of Carters, Georgia) but just missing the gold fields at

Dahlonega. They passed southwest into Alabama where the army’s supplies

were ravaged in a day-long battle, disastrous for both sides, with the war-

riors of Chief Tascaluza at Mabila; the Mabila lost perhaps as many as 3,000

men. In the aftermath of the battle, de Soto made a fateful decision not to

avail himself of provisions awaiting him by prearrangement on ships at Pen-

sacola Bay lest his dispirited men seize the ships and desert the enterprise.

“From that day,” wrote one of the chroniclers, who interviewed survivors,

“as a disil usioned man whose own people have betrayed his hopes . . . he

went about thereafter wasting his time and life without any gain, always

traveling from one place to another without order or purpose.”11 Those sub-

sequent meanderings took the army northwest into Mississippi, where they

First European Contacts · 33

wintered in 1540–41 among the hostile Chickasaw near Tupelo, to whom

they lost more men, horses, and more than 300 pigs. Sometime in May 1541

they discovered the great river Mississippi, crossing it on flatboats a few

miles south of Memphis on 19 June. Another difficult winter (1541–42) was

spent in Arkansas, where the men suffered greatly from cold temperatures,

sickness, and malnutrition; several died, including the interpreter Juan

Ortíz.

In March 1542, de Soto led the survivors back through southern Arkan-

sas to the Mississippi, where, on 21 May, the would-be conquistador himself

died of an unidentified disease and was secretly interred in the bed of the

river. Campmaster Luis Moscoso de Alvarado succeeded to command and

led the army in an overland attempt to reach New Spain, but by October

they had gotten no farther than the Trinity River in eastern Texas. There,

with no further signs of maize-cultivating natives, they were forced back to

the Mississippi, which they reached in December. They constructed seven

keeled boats and boarded them on 2 July in an attempt to escape downriver

to the Gulf. A sail and seven oars on each vessel provided propulsion, which

was desperately needed on two occasions when riverbank warriors in ca-

noes pursued them with arrows. After successful y reaching the mouth of

the Father of Waters, the tiny fleet pressed westward along the Gulf beaches