The History of Florida (35 page)

Read The History of Florida Online

Authors: Michael Gannon

Tags: #History, #United States, #State & Local, #Americas

Revolution. The newly restored Spanish rule claimed sway over the same

colonial boundaries in Florida as established by the British: two separate

colonies, West and East, divided at the Apalachicola River, ranging west

proof

as far as the Mississippi and governed from two capitals, Pensacola and St.

Augustine. The St Marys River formed the boundary between Spanish East

Florida and the new U.S. state of Georgia. West Florida was the larger of

the two Floridas. It extended from the Chattahoochee and Apalachicola

Rivers on the east to the Mississippi River and the Isle of Orleans on the

west. The Gulf of Mexico and the Louisiana Lakes Borgne, Ponchartrain,

and Maurepas formed its southern boundary. There was disagreement over

the northern boundary of West Florida. Initial y, the northern border had

been set at latitude 31° north, but in 1764 it was moved up to 32°28" in order

to include more fertile lands and fur-trapping ranges. The United States

and Great Britain accepted the thirty-first parallel as the boundary. Spain

considered the international line to lie considerably northward, and the

boundary dispute immediately embittered relations between the United

States and Spain. As a result, Spanish West Florida became the first victim

of what some historians would later cal Manifest Destiny. The history of

Spanish West Florida from 1783 to 1821 is real y a history of defeats—some

economic, some diplomatic, and a few military—that ultimately cost Spain

her newly regained colony.

· 162 ·

The Second Spanish Period in the Two Floridas · 163

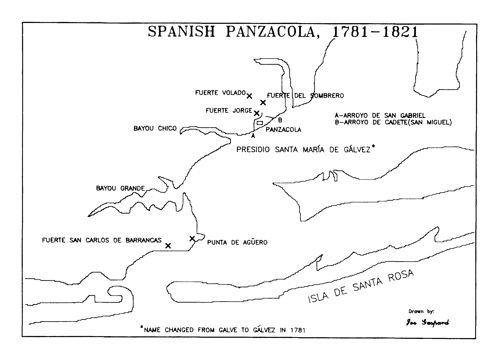

A plan of the Pensacola Bay region in the period 1781–1821. Pensacola (Panzacola) was

the capital of Spanish West Florida. Other towns of consequence in the colony were

Mobile, Baton Rouge, and Natchez. Drawn by Joe Gaspard.

proof

For a long time, most histories of the Second Spanish Period of the Flo-

ridas reflected the Anglophile viewpoints of earlier historians. The era is

general y portrayed as an interval of decline wedged between the British

and American periods, merely awaiting an inevitable takeover by the United

States and its institutions. That view arose largely from reliance upon Eng-

lish-language sources, which aggrandized conditions during the two peri-

ods when English was the official language while minimizing developments

during the Spanish period. David J. Weber observed that Englishmen and

Anglo-Americans writing at the time of the Second Spanish Period “uni-

formly condemned Spanish rule.” They saw only Spanish misgovernment,

which “seemed the inevitable result of the defective character of Spaniards

themselves.”1 More recent attention to Spanish-language documents ques-

tions that negative assessment.

In 1784 there was widespread doubt that the republican government of

the new United States could control even its large landmass awarded in

treaty negotiations, much less take over additional territory in the Floridas.

Only four towns of any consequence contained the urban populations of

West Florida: Mobile, Baton Rouge, Natchez, and Pensacola, the capital. In

164 · Susan Richbourg Parker and William S. Coker

addition to the military forts in each of those towns, there were two others

in the interior, Fort Choiseul (York) and Fort Toulouse. Without counting

the native peoples, the population of West Florida was approximately 3,660

in 1785 and 8,390 in 1795. Between 1795 and 1814, the population grew sig-

nificantly, but substantial territorial losses to the United States reduced the

area and population of West Florida by 50 percent or more.

In St. Augustine, troops sent from Cuba again walked the capital’s streets

gossiping in Spanish, former émigré residents moved in to reclaim old

homes, and Mass was heard again in the parish church. In the countryside,

English-speaking settlers debated what their fate might be under the new

regime while they planted their crops and felled timber. Many British citi-

zens remained in East Florida in the hope of taking advantage of a failure

of the United States. These former British subjects joined Spanish soldiers

and returning families, their slaves, free blacks, white and black immigrants

from the United States, refugees of both races from the Caribbean, especial y

Saint-Domingue (Haiti), sailors and opportunists of many nationalities, and

Seminole Indians in the interior of the peninsula to make East Florida’s

Second Spanish Period the most cultural y and racial y heterogeneous era

of its history until the second half of the twentieth century. The population

of the countryside was more homogeneous than that of the towns and ports.

proof

In the first years of the Second Spanish Period, rural residents beyond the

immediate outskirts of St. Augustine were overwhelmingly Protestant; they

were planters or farmers and natives of the southern British colonies, espe-

cial y South Carolina, and about half owned slaves. The diversity among the

province’s populace contributed to the unsettledness of the era.

The role and power of the military and the Roman Catholic Church dur-

ing the Second Spanish Period were diminished in comparison to the first

two centuries, although both institutions remained strong presences. Span-

ish West Florida was under the jurisdiction of the civil and military com-

mandant stationed at Pensacola. The title of his office was later changed to

governor, but the duties remained essential y the same. All of West Florida’s

commandants/governors were military officers, normal y appointed to

serve a term of five years. In practice, they stayed until they were formal y

relieved of duty. Thirteen officers served as commandant/governor of the

colony between 1781 and 1821. Colonel Vicente Folch y Juan held office the

longest, 1796–1811; Colonel Arturo O’Neill y Tyrone was second in length of

service, 1781–94.

The duties of these officers included supervision of the military, Indian

affairs, foreign relations directly affecting the colony, financial matters and

The Second Spanish Period in the Two Floridas · 165

the economy, land grants, and the church. These officers were under the

supervision of the governor-general and the intendant of Louisiana and

West Florida until 1806. After that date, the captain-general of Cuba as-

sumed direct command over West Florida’s governors. Although within the

boundaries of Spanish West Florida, the Natchez District, whose principal

officer was changed from a commandant to a governor in 1787, was under

the direct command of the governor-general of Louisiana. Colonel Manuel

Gayoso de Lemos served there from 1789 to 1797, by which time the United

States had acquired the area. Gayoso then became the governor-general of

Louisiana and West Florida.

The Roman Catholic faith was the only religion official y permitted in the

Spanish Floridas although persons of other religious denominations could

worship in private. The church in West Florida followed the same pattern

of jurisdiction as did the civil and military government: It was under the

governor of West Florida except for strictly religious matters. For religious

matters, after 1787, it was under the auxiliary bishop of Louisiana and West

Florida. Father James Coleman served as the priest of the parish of San

Miguel in Pensacola from 1794 until 1822. In 1806, he was appointed the

vicar-general and ecclesiastical judge of West Florida. He became perhaps

the best known of all the priests in colonial West Florida. After 1806, con-

proof

fusion reigns about who had official jurisdiction over the church in West

Florida, but Father Coleman looked to the bishop of Havana.

By 1795, it is estimated, about 15 percent of the population of West Florida

was Protestant. Father Coleman’s religious censuses of Pensacola in 1796–

1801 indicated that about 25 percent of its population was Protestant; this

strong showing resulted from the presence of British residents who decided

to remain in West Florida, as wel as from Protestant immigration after 1783.

Mobile, with its large French population, remained predominantly Catholic.

Spain continued to subsidize a military presence in East Florida finan-

cial y disproportionate to the colony’s productivity, for East Florida’s rai-

son d’être was still to protect the richer areas belonging to the Crown, par-

ticularly the mineral wealth of Mexico. But the military budget no longer

overwhelmingly supplied the financial base of the province, as in the First

Spanish Period, and over the years it became an ever-smal er part of the

economy, reflecting the vicissitudes of the Spanish Crown and government.

East Florida’s governors complained about the irregular arrival of monies

needed to maintain the troops and fortifications, but the accounting records

reveal that the funds usual y did arrive and were usual y on time; the prob-

lem lay with the manner of distributing funds in an annual lump sum. Over

166 · Susan Richbourg Parker and William S. Coker

the years, diminishing troop strength meant smaller budgets, which trans-

lated into the ever-decreasing financial and social influence of the military.

Between 1790 and 1800, East Florida lost 30 percent of its soldiery, and units

continued to diminish in strength although at a slower rate.

The weakened role of the church in East Florida reflected its position

throughout the Spanish empire, as the monarchy and its bureaucracy gained

power by taking over functions once performed by the church, such as ap-

proval of marriages. In East Florida, the financial well-being of the church

was tied to that of the provincial government through its inclusion in the

defense budget. Although the Franciscans had wished to return, there was

no revival of the missions in Florida to paral el the prosperity of the or-

der’s missions in California during the late eighteenth century. Catholic

priests visited East Florida’s largely Protestant rural population soon after

the Spaniards returned and baptized many young children, but there was no

subsequent establishment of parishes or church-sponsored schools outside

of St. Augustine. Thus, the opportunity to incorporate the residents of the

countryside into the province’s society was lost, and they remained English-

speaking, unchurched, and omitted from most official festivals and celebra-

tions—events that revolved around religious feast days and commemorative

rituals. For example, in 1789, when the residents of St. Augustine staged a

proof

three-day festival for the coronation of King Carlos IV, featuring Masses, an

enthroning reenactment, parades, and plays, no counterpart took place in

the rural area to involve the settlers in that moment of national celebration.

West Florida had the potential of being an important colony economi-

cal y. Early on, the area did reasonably wel with tobacco, indigo, and

lumber. Tobacco flourished but soon lost out from overproduction and

competition from Mexico. Indigo also did wel until pol ution problems

developed. Timber, especial y ships’ masts, yielded a good return, but the

market was limited. And, unfortunately, a cotton boom came too late. Sea-

food and livestock production never reached their potential. The population

was too small to support large-scale manufacturing and related industries.

For Spain, West Florida was simply not a profit-making colony. Its impor-

tance lay in its strategic position on the Gulf coast. There was one way to

make a profit—the Indian trade—but the profit went to the British, not to

the Spanish.

The person who was to have an important economic impact on West

Florida was the Scotsman Wil iam Panton, one of the partners in the In-

dian trading firm of Panton, Leslie and Company. The company had already

achieved considerable success in East Florida. Panton and his assistant John