The History Buff's Guide to World War II (39 page)

Read The History Buff's Guide to World War II Online

Authors: Thomas R. Flagel

A desk officer until appointed naval headmaster, the intelligent but insular Toyoda directed the Imperial Fleet into an all-or-nothing interception of the American attack on S

AIPAN

. Before his pilots left their carriers, he radioed: “The rise and fall of Imperial Japan depends on this one battle. Every man shall do his utmost.” Outgunned, undertrained, and outnumbered two to one, his air arm flew into what Americans later called “the Great Marianas Turkey Shoot.” Eighty percent of Toyoda’s planes were shot down, more than three hundred aircraft. The U.S. lost fewer than thirty planes. The admiral also lost seventeen of twenty-five submarines and three of nine carriers.

69

In October 1944, he pushed again for a “final battle” at L

EYTE

G

ULF

in the Philippines. Plucked of his planes and submarines, Toyoda soon forfeited the bulk of his surface ships. His strike forces totaled an astounding six carriers, nine battleships, twenty cruisers, and thirty-five destroyers. A few days later only six battleships and a handful of cruisers remained above water. Afterward Toyoda fully endorsed the use of kamikaze in a desperate attempt to hold on to the Philippines. To ensure the best results, he ordered the use of Japan’s best pilots.

70

And still there was one more try in him. To the battle of O

KINAWA

Toyoda sent the

Yamato

, the largest battleship ever constructed. Legend states that the warship and its small complement of support vessels were given enough fuel for a one-way trip. Regardless, they had no air cover. Dismembered by direct hits from twenty torpedoes and bombs, the

Yamato

sank to the bottom of the ocean.

71

Removed from his post, Toyoda was promoted to navy chief of staff. Serving in Tokyo up to the end, he passionately argued for a continuation of the war, even after the second atom bomb fell on Nagasaki.

72

Brought to trial for war crimes, Toyoda Soemu was one of the few senior officers of the Japanese Empire to be acquitted on all counts.

7

. IRWIN ROMMEL (GERMANY, 1891–1944)

Yes,

the

Irwin Rommel. Chivalrous, charming, aggressive, and perceptive, Rommel was a phenomenon in the First World War. A mere low-grade officer, he personally led raids in France, Romania, and Italy, capturing thousands with a fraction of the troops. As a high-ranking leader in the Second World War, his maverick, reckless exploits were lethally out of place. He routinely disobeyed orders, displayed a contempt if not ignorance of logistics, and all but refused to cooperate with fellow officers.

Assigned to Libya in February 1941 to head the newly formed Afrika Korps, Rommel was ordered to stay on the defensive. Instead he launched an attack on the British protectorate of Egypt. Though he won ground and frightened the Commonwealth, he captured no major ports or key cities. He managed, however, to waste fuel and equipment earmarked for the impending invasion of Russia. Upon hearing of Rommel’s escapade, chief of staff Franz Halder fumed that Rommel had gone “stark mad.”

73

Eventually beaten back to Libya, Rommel at least captured its vital port of Tobruk (after four bloody attempts), which strengthened his supply line from Italy and Germany. Instructed to remain there, he headed eastward again. In the summer and fall of 1942, he lost three successive battles, including S

ECOND

E

L

A

LAMEIN

, which began while he was on sick leave. His withdrawal of one thousand miles west to Tunisia, though often described as “brilliant,” saved only a fraction of his command. It was also the longest continuous retreat in German military history up to that time.

Later scoring a modest victory against inexperienced U.S. and French troops at Kasserine Pass along the Algeria-Tunisia border, he failed to coordinate with fellow commander Gen. Hans Jürgen von Arnim and lost the initiative. He returned to Germany, but his troops could not follow. Rommel’s desert adventures compromised Axis strength in the Mediterranean, leaving no viable route for evacuation. The Axis subsequently surrendered more men in Tunisia (two hundred thousand) than at S

TALINGRAD

(ninety-one thousand).

74

Later in 1943, while his cohorts fought for their lives on the eastern front, Rommel transferred to quiet northern France, where he wasted time and resources on the tactically futile A

TLANTIC

W

ALL

. In 1944, when

INTELLIGENCE

and climactic conditions indicated a May–June window for an Allied invasion, he left for Germany to visit his wife on her birthday—June 6, 1944.

Overall, German historians think little of Rommel. His reputation stands high in the West partially because he was stationed in the West. Except for a brief staff job in the invasion of Poland, he served in France and Africa, where he initially faced green troops and commanders who vaunted his “brilliance” rather than admit to their own shortcomings. Rommel vaingloriously augmented his inflated status by courting journalists and photographers throughout his tenure.

75

Time and again Rommel’s reputation remained intact because, in truly critical moments, he was usually absent. He also took leave of another important event. Conspirators asked him many times to support the July 1944 bomb plot against Hitler. But contrary to legend, Rommel strongly opposed murdering his Führer.

76

Constantly paired with U.S. Gen. George S. Patton Jr., the two never met in battle. Rommel left Tunisia, Italy, and France before his armies engaged Patton’s.

8

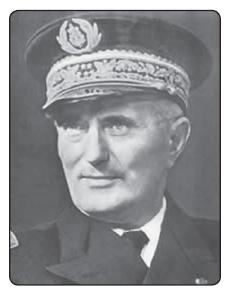

. JEAN FRANCOIS DARLAN (FRANCE, 1881–1942)

An American officer described J. Francois Darlan as “a short, bald-headed, pink-faced, needle-nosed, sharp-chinned little weasel.” Still, the French admiral could be reduced to a single word: indecisive.

77

Chief of the navy at the time of France’s surrender, Darlan initially hinted that he would enjoin his fleet, the fourth largest in the world, to the Allies. He instead sent his European-based vessels to French colonial North Africa. Britain retaliated by bombarding the warships on the Algerian coast, sinking the battleship

Dunkerque

and killing more than a thousand sailors.

Infuriated, Darlan forged closer French relations with the Third Reich. For a time he favored German victory, which he believed would enable France to control the oceans and overtake the British Empire. For his work, Darlan was promoted to commander in chief of Vichy’s armed forces.

Darlan was in Algiers in November 1942 when the Allies invaded, and he ordered French troops to fight back. When American envoys arrested him two days later, Darlan denied having any military authority. After further negotiations, he relented and ordered his men to cease fire. But when he heard that the Vichy government was angered by his capitulation, Darlan announced a resumption of the fighting. Twenty-four hours later, when Germany invaded southern France, Darlan hinted he would help the Allies.

78

Weathering these bizarre U-turns from his headquarters in Gibraltar, the normally patient D

WIGHT

D. E

ISENHOWER

finally cracked. “What I need around here,” seethed Ike, “is a damned good assassin.” Eisenhower’s offhanded wish came true. For unknown reasons, an obscure young Frenchman visited Darlan at his palatial Algiers office on Christmas Eve, 1942, and shot him dead.

79

Darlan’s family had a legacy of contesting Britain. His great-grandfather was killed by the British in the battle of Trafalgar.

9

. WILHELM KEITEL (GERMANY, 1882–1946)

A competent staff officer with no particularly outstanding qualities or achievements, Wilhelm Keitel was as surprised as anyone when he was promoted in 1938 to chief of staff of the high command of Germany’s armed forces, in charge of all military strategy. In an instant, he had become the second-highest-ranking member of the German general staff, right below der Führer.

Whatever latent talents Keitel possessed remained in hibernation, as he quickly became Hitler’s most blindly loyal servant. So repugnant were his kowtowing antics, other officers began to call him “Laikeitel”—a German play on the word “lackey.”

But this lackey simultaneously protected Hitler from voices of dissension and crushed morale and communication among Germany’s high command. Between stroking his leader’s confidence, he occasionally informed Hitler of “defeatist” voices among general officers.

On one instance he demurred. When Hitler expressed a desire to invade the Soviet Union in 1940, the normally spineless Keitel criticized the idea. Troops were too entrenched in France. Necessary tanks, planes, and winter gear were not available. The attack would have to happen early in the spring to avoid the Russian winter. Yet when the same conditions applied the following summer, Keitel succumbed to Hitler’s bidding and enthusiastically supported the invasion.

80

Though the field marshal often neglected to stand up for his military, he found time to initiate atrocities in the name of his boss. He endorsed the shooting of captured Soviet political commissars, authorized SS extermination programs, and ordered civilians to murder downed Allied airmen. “Any act of mercy,” he insisted, “is a crime against the German people.”

81

Found guilty in Nuremberg of crimes against peace, war crimes, crimes of international conspiracy, and crimes against humanity, Keitel was executed in 1946.

At Nuremberg, Wilhelm Keitel requested to be shot, as it was the proper method of execution for officers. They hanged him.

10

. MUTAGUCHI RENYA (JAPAN, 1888–1966)

“I started off the Marco Polo Incident, which broadened out into the China Incident, and then expanded until it turned into the Great East Asian War.” Humility was not a strongpoint of Japan’s Lt. Gen. Mutaguchi Renya. Neither were patience, foresight, troops, morale, matters of supply,

etc.

And it is entirely possible his regiment did initiate the C

HINA

I

NCIDENT

in 1937. Mutaguchi was one of the more rabid officers of Japan’s rogue Kwantung Army in Manchuria.

82

Later, at the head of a division, he performed admirably in the February 1942 conquest of S

INGAPORE

. But at the time he was under the guidance of the cunning and reliable general Yamashita Tomoyuki.