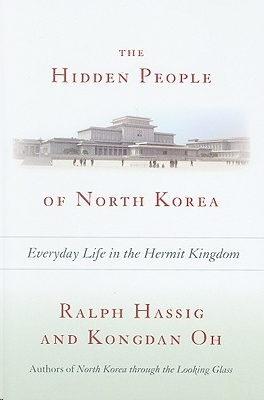

The Hidden People of North Korea

Read The Hidden People of North Korea Online

Authors: Ralph Hassig,Kongdan Oh

Tags: #Political Science, #Human Rights, #History, #Asia, #Korea, #World, #Asian

Published by Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

http://www.rowmanlittlefield.com

Estover Road, Plymouth PL6 7PY, United Kingdom

Copyright 2009 by Ralph C. Hassig and Kongdan Oh Hassig

All rights reserved

. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hassig, Ralph C.

The hidden people of North Korea : everyday life in the hermit kingdom / Ralph Hassig and Kongdan Oh.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-7425-6718-4 (cloth : alk. paper)—ISBN 978-0-7425-6720-7 (electronic)

1. Korea (North)—Social life and customs. 2. Korea (North)—Social conditions. 3. Korea (North)—Economic conditions. 4. Political culture—Korea (North) 5. Korea (North)—Politics and government—1994– 6. Kim, Chong-il, 1942—Influence. I. Oh, Kong Dan. II. Title.

DS932.7.H37 2009

951.9305—dc22

2009029786

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Printed in the United States of America

We must envelop our environment in a dense fog to prevent our enemies from learning anything about us.

—Kim Jong-il

Preface

Kongdan (Katy) Oh’s parents came from North Korea, although in the final years of the Japanese occupation they lived in China. As members of the educated class, her parents were understandably wary of the new communist “working-class” government being set up in the North, and with hundreds of thousands of other North Koreans, they fled to the South before the border was closed. Since coming to the South, they have not heard anything from their relatives who stayed behind.

Under a succession of South Korean authoritarian governments that viewed the North as an enemy state, school children had no opportunity to learn anything about North Korea except what the authorities permitted under the National Security Law—still in force today but greatly relaxed since the end of the Cold War. Nor was information about other communist states available. It was not until she enrolled in graduate study at the University of California, Berkeley, that Oh was able to begin an objective study of North Korea.

Upon graduation, she went to work for the RAND Corporation with a primary assignment to analyze how North Korea could threaten the national security of the United States. In practice, this meant that much of her work, first at RAND and then at the Institute for Defense Analyses, has been related to North Korea’s weapons of mass destruction. A secondary field of study is the nature and stability of the Kim regime, which after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, was dubbed one of the three “axis-of-evil” governments by the George W. Bush administration. Missing from this study, and from most studies of North Korea, is an analysis of how the ordinary people live; since they have absolutely no voice in formulating their government’s policies, what happens to them is of little concern to foreign governments.

The book’s first author, Ralph Hassig, developed an interest in North Korea after being asked to edit and coauthor reports and articles with Katy Oh, who happens to be his wife (they met while they were teaching for the University of Maryland University College in Seoul). Since the early 1990s, Hassig has devoted most of his research time to North Korean studies, doing much of the English-language writing and research and relying on Oh to do most of the presentations, Korean-language research, and networking with other North Korea watchers in South Korea and around the world.

After completing our first book on North Korea, which was published in 2000, we decided to write something about the North Korean people, a topic that up to that time had been extremely difficult to research because few North Koreans could get out of their country and few foreigners could get in. This situation began to change in the late 1990s as thousands of North Koreans escaped into China; by 2009, over fifteen thousand of these defectors had made their way to South Korea, where they provide valuable information about everyday life in the modern-day hermit kingdom they were forced to leave behind. By interviewing them and by talking with other interviewers and reading their reports, it is now possible to piece together what life is like in North Korea today.

Along the way we have become indebted to many people for information, insights, and materials pertaining to the North Korean people. We would particularly like to thank Dr. Seong Il Hyun, currently a senior research fellow at South Korea’s Institute for National Security Strategy and formerly a North Korean diplomat, who was kind enough to read through our manuscript and give it his personal approval. Some of the defectors we interviewed wish to remain anonymous to protect their identity (most of them have relatives still living in the North), while others have gone public with their testimony, although sometimes they adopt new names in South Korea. These former North Koreans, along with numerous researchers from other countries who have directly contributed to this book, are listed here in alphabetical order: Amii Abe, Seungjoo Baek, Stephen Bradner, William Brown, Jin-Sung Chang, Seong-Ryoul Cho, Charles Hawkins, Takeshi Hidesada, Yoshi Imazato, Eun Chan Jeong, An-sook Jung, Chul Hwan Kang, Byeong-Uk Kim, Kap-Sik Kim, Koo Sub Kim, Kwang-Jin Kim, Kyung-Hie Kim, Sang-Ryol Kim, Seung-Chul Kim, Tae Hoon Kim, Taewoo Kim, Doowon Lee, Duk-Haeng Lee, In Ho Lee, Won-Woong Lee, Young-Hwan Lee, W. Keith Luse, Mitsuhiro Mimura, Marcus Noland, Seung-Yul Oh, Young-Ho Park, Scott Snyder, Jae Jean Suh, Ven. Pomnyun Sunim, Chang Seok Yang, and Yeosang Yoon.

About Korean Names and Pronunciation

We’d like to say a few words about the romanization and pronunciation of Korean names. The Korean alphabet is a wonderfully transparent writing system, but when it comes to transliterating it into roman letters, there are several alternatives. Until 2000, the most common method was to use the McCune-Reischauer System, a version of which we use in this book because it is familiar to several generations of readers and because it is also used by North Koreans to translate their works into English. We have simplified the system by dispensing with apostrophes (used to indicate aspirated consonants) and diacritical marks above vowels. The resulting simplification will be admirably suited to the needs of most readers, and those who are familiar with Korean will be able to translate back into Korean. Since 2000, South Korea’s Ministry of Culture and Tourism has put forward a somewhat different method of transliterating Korean into English. This method, the Revised Romanization, has met with some resistance, even from major South Korean newspapers, but now seems to have been adopted widely in South Korea. However, because it looks somewhat strange to many foreigners, ourselves included, we have chosen to stay with the older system.

In Korean names, the family name usually comes first, followed by one or two given names. Some Koreans hyphenate their two given names, others write them separately, and some even combine the two (for example, the book’s second author). The official North Korean approach is to write them separately, as in Kim Il Sung and Kim Jong Il; however, to make it clear to foreign readers which are the family names and which are the given names, we have decided to use an equally popular approach and hyphenate the two names, hence, Kim Il-sung and Kim Jong-il. Throughout the book Korean names are presented in this manner except where Koreans (outside of North Korea) specifically use another form.