The Heart Has Reasons (24 page)

Janet Kalff at age ninety-nine.

“Where does your daughter-in-law live?” She gave him my address.

“And where is your son?” Well, he was in Vught, which wasn’t a very good recommendation.

A silence fell in the room after she’d told the whole truth, and she sat there trembling. After a long pause, the NSBer said, very politely, “Madam, I have an old mother, and she thinks just the way you do. You’ll hear nothing more about it.”

We all went into hiding for a few weeks because we were afraid they would come after us, but they never did. In fact, Anton was released from Vught a short time later.

I visited janet kalff again a couple of years later, and, at the age of ninety-nine, she repeated the story to me using almost the same exact words. When I asked her what became of Rosa, she gave me a sad look and took a thin gray sheet of paper out of her drawer—a letter that Rosa had sent her from the Apeldoorn prison. She explained that this letter, written just a day before Rosa was deported to Westerbork, was the last communication they ever had from her:

I believed, but wasn’t certain of, my faith in God during difficult moments. But

now I realize that every human being has to accept what comes. If God wants

the best for me, He will help me, but I must prepare myself for the worst—not the punishments, not even the torture that I expect to endure, but my own

self-reproach and regret for my foolishness. And I shiver to think that totally

innocent people might now face great difficulties and dangers because of me.

So perhaps it is right that I should suffer the same fate that so many others

have

suffered. Forgive me, dear, dear, people!

The little plant that I have in my cell, bought for my sweetheart’s birthday, bends over more and more owing to lack of sunlight. I haven’t

reached that stage yet. Certainly, I am bowed, but I shall not break. Nothing they can do can really touch me. But thinking things over and remembering the many friends I made, people I loved with all my heart, then . . . no, I will think of them another day. But what if there is not another day?

If I should read these pages years from now, I would laugh at their

sentimentality. “Last words of a girl in the full bloom of her youth.” I will

stop now. Who these words are for, I don’t know. Someone will read them

someday—whoever you are. I hope the Kalffs will read them, and especially

the old grandmother, whom I pray for every day. Just one more thanks for all

the love and understanding I have been given.

Your deeply sad but grateful,

Rosa

EIGHT

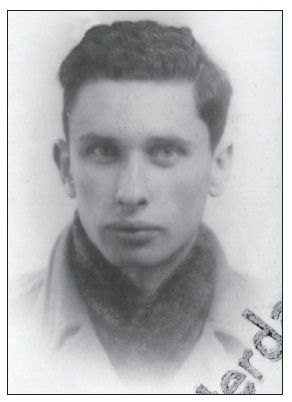

~ PIETER MEERBURG ~

MASTERMIND OF THE HEART

Compassion is a verb.

—

Thich Nhat Hanh

Piet meerburg is so expressive that I feel I would be able to understand him even if he barely spoke English—it’s as if his spirit leaps ahead of his words. Or perhaps it’s that his voice, so vigorous yet nuanced, can pack so much emotion and conviction into a simple phrase.

Piet was born in 1919, but his life as an octogenarian is an unusually active one. When I called recently, he had just gotten back from Boston, having attended an honorary ceremony for a friend; the next time

I rang, he was leaving for a fortnight in Italy. But his is not the leisure of retirement. A successful and creative businessman, he usually puts in close to a full day at the office, continuing to work in partnership with his eldest son.

I met with Piet on the fifth of December, which, as Clara Dijkstra explained, is Sinterklaas—the day presaging Christmas in the Dutch calendar on which children customarily receive gifts. Piet’s life has been a gift to the hundreds of Dutch children who were rescued by the Amsterdam Student Group: Piet was one of the group’s organizers, and, according to those who worked with him, its leader and mastermind.

He welcomed me into his spacious apartment on Beethovenstraat in Amsterdam with a broad smile, his open face, with its generous mouth and bright eyes, crowned with a halo of pure white hair. The subdued afternoon light washed through the sheer curtains as we talked until dusk. Piet’s words were equally pellucid: candid, frank, nearly transparent. A dynamic man who clearly possesses a wellspring of

élan vital

, he answered my questions in a direct and sometimes outspoken way, his mind not only making connections between past and present but factoring in the future as well. His level gaze mirrored his conviction that the Holocaust must be looked at squarely; in his steel-blue eyes, I felt his resolve to do what he could to set the historical record straight.

I was very anti-Nazi even before the war. I’m amazed that more people couldn’t see what was coming, because it was already clear in ’36 and ’37. You could read

Mein Kampf

, there were stories in the newspapers. And that’s why, as a college student at the University of Amsterdam, I joined a movement called

Eeheid Door Democratie

—Unity Through Democracy. All the political parties except for the fascists were represented, and we had a lot of meetings in which people could ‘learn about the dangers of fascism—especially Hitler’s National Socialism.

Then the Germans invaded in May of ’40. The first six months they kept a low profile, and were careful not to provoke anyone. Then in October they made the professors sign a form stating their ethnic origin. A month later all the Jewish professors were forced to resign. We had protests, and some students were arrested. We despised what the Germans were doing, but we didn’t realize how dangerous it was to try to resist them.

The anti-Jewish laws that prohibited Jews from going to the shops,

or on the train, didn’t come all at once, but gradually. Each month, the Nazis would tighten the screws. I remember a turning point: I had a Jewish friend in one of my classes who was called home one day because the Germans were at his house and they wanted to talk to him. He never returned. Ever. So then you say, “This is ridiculous. What am I doing here? Yes, I am studying law, but look at what the law has become. Look at what is going on before my very eyes!” Finally you draw the line: “This far, no further.”

In ’41 a group of us got together with the aim of resisting in some way. We figured that those who struggle can lose, but those who don’t struggle have already lost. So we carried out protests, circulated petitions, did some sabotage. After about six months of this, Jür Haak found his way to one of our secret meetings. He was in contact with the Utrecht Kindercomité, and they were already busy hiding Jewish children. So he said, “They’re sitting in Utrecht, while you’re here in Amsterdam where there are so many Jewish children. Why don’t we help them?” And that’s how the child rescuing started.

Jür introduced me to Wouter van Zeytveld, a guy just out of high school, who became my partner in the children’s work. He was Marxist, very leftist, and came from a family that was very much that way. And he was in love with Jür Haak’s sister, Tineke. So Wouter and me and Jür and Tineke started working together, along with the other members of the group including my girlfriend Hansje van Loghem. By the end of ’42, we had gone beyond just helping the Utrecht group; we were carrying out the work ourselves.

By then we were a group of about twelve, mostly guys. That shouldn’t surprise you, because doing this work required that you ride on the trains, and in those days that was a very dangerous thing for a young man to do. The Germans needed labor, and might pick you up and make you work for them. Besides, if you were a young man traveling with an infant, it looked suspicious, and you might get questioned. That was a job better done by the girls. So they would ride on the trains and take the children to safe addresses, while Wouter and I stayed in Amsterdam and did the organizing piece.

Of course, it wasn’t 100 percent. Geert Lubberhuizen, who started out in that same Utrecht group, made me some wonderful false papers that said I was an inspector for the railway system. Those papers gave me a very protected situation; I could ride on the train, and when the Germans saw I was an inspector, they left me alone.

One of the first things I did was to go up north to Friesland. I

wanted to talk to the ministers there, because most of them could be trusted, and if you found a good one, he knew exactly who was “right” and who was “wrong” in the entire town. So I made contact with some of the ultra-orthodox Calvinist ministers and told them about the razzias taking place in Amsterdam, and how we needed to find places for the Jewish children to hide. And here’s the astonishing thing: they didn’t believe me. They simply didn’t believe the stories I was telling them. Perhaps it was because they hadn’t heard about it from anyone else. As blackstockings, they kept to themselves, plus they were in the hinterlands. They didn’t know what was going on in Amsterdam. And also, you have to remember, I was only twenty years old. Perhaps they didn’t take me seriously.

But finally I found a blackstocking minister in the town of Sneek who believed me. He was a fantastic man. And then the Resistance began to spread like wildfire there. Within one month, we had set up a network in Sneek and Leeuwarden. After two months, everyone believed me because they were hearing the same stories from other people, and I was able to get something going in Joure also. The good thing was, once they knew that I was telling them the truth, they were behind me 100 percent. As Wouter used to say, “Once those fanatical Frisians back you in something, their support is so solid that you can practically build a house on it.”

Next I traveled south to the little town of Tienray in the province of Limburg, another area safer than most. I set up another network there, and by the beginning of ’43 we had placed about 130 children in Limburg alone.

The first step was always to get the permission of the parents. At the beginning, a lot of Jewish people thought that they were going to be sent to a work camp—they didn’t realize the danger. I’d talk to the parents and they would say, “Well, we’ll have to work in Poland and it won’t be nice, but we want our children with us.” Even later, some of them still thought they could get through it together. The point is: not all the parents wanted our help. And if that was their decision, we didn’t argue with them. But if they said yes, we did everything we could to help them.

Following the July razzias of ’42, there came a most important development:

De Hollandsche Schouwburg

. Schouwburg means theater, and the Hollandsche Schouwburg had been the place in Amsterdam where people went to hear vaudeville before the war. But the Germans gutted it that summer, and made it into a detention center for Jewish people. It still exists today, and you must see it. It’s much more important than

the Anne Frank house, because that is the spot where all the misery and death began. When the Nazis picked you up, they brought you to that theater, and after two or three weeks, they would transport you to Westerbork. From Westerbork they would send you east to Auschwitz and the other camps in Poland. And across the street from the theater was the Creche, and that was where they kept the children. The babies were brought there, too—they had some Jewish girls working there to look after them. So what we decided to do was to try to save those infants and children that were being held in the Creche.