The Hare with Amber Eyes (17 page)

Read The Hare with Amber Eyes Online

Authors: Edmund de Waal

There are things that the children smell that are part of their landscape: the smell of their father’s cigar smoke in the library, their mother, or the smell of schnitzel on covered dishes as it is carried past the nursery for lunch. The smell behind the itchy tapestries in the dining-room when they creep behind them to hide. And the smell of hot chocolate after skating. Emmy makes this for them sometimes. Chocolate is brought in on a porcelain dish, and then they are allowed to break it into pieces the size of a krone and these dark shards are melted in a little silver saucepan by Emmy over a purple flame. Then, when it is glaucous, warm milk is poured over it and sugar stirred in.

There are things that they see with complete clarity – the clarity of an object seen through a lens. There are also things that they see as a blur: the corridors chased along, corridors that go on for ever, one gilded flash of a picture after another, one marble table after another. There are eighteen doors if you run all the way round the courtyard corridor.

The netsuke have moved from a world of Gustave Moreau in Paris to the world of a Dulac children’s book in Vienna. They build their own echoes, they are part of those Sunday mornings’ story-telling, part of

The Arabian Nights

, the travels of Sinbad the Sailor and the

Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám

. They are locked into their vitrine, behind the dressing-room door, which is along the corridor and up the long stairs from the courtyard, which is behind the double oak doors with the porter waiting, which is in the fairytale castle of a

Palais

on a street that is part of

The Thousand and One Nights

.

The century is fourteen years old, and so is Elisabeth, a serious young girl who is allowed to sit at dinner with the grown-ups. These are ‘men of distinction, high civil servants, professors and high-ranking officers in the army’ and she listens to the talk of politics, but is told not to talk herself unless she is talked to. She walks with her father to the bank each morning. She is building up her own library in her bedroom: each new book has a neat EE in pencil and a number.

Gisela is a pretty young girl of ten who enjoys clothes. Iggie is a boy of nine who is slightly overweight and self-conscious about it; he isn’t good at maths, but likes drawing very much indeed.

Summer arrives, and the children travel to Kövecses with Emmy. She has ordered a new costume, black with pleating to the blouse, for riding Contra, her favourite bay.

On Sunday 28th June 1914 the Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Hapsburg Empire, is assassinated in Sarajevo by a young Serbian nationalist. On Thursday the

Neue Freie Presse

writes that ‘the political consequences of this act are being greatly exaggerated’.

On the following Saturday, Elisabeth writes a postcard to Vienna:

4th July 1914

Dearest Papa

Thank you so much for arranging about the Professors for next term. Today it was very warm in the morning so we could all go swimming in the lake but now it is colder and it may rain. I went to Pistzan with Gerty and Eva and Witold but I didn’t like it very much. Toni has had nine puppies, one has died and we have to feed them with a bottle. Gisela likes her new clothes. A thousand kisses.

Your Elisabeth

On Sunday 5th July the Kaiser promises German support for Austria against Serbia, and Gisela and Iggie write a postcard of the river at Kövecses: ‘Darling Papa, My dresses fit very well. We swim every day as it is so hot. All well. Love and kisses from Gisela and Iggie.’

On Monday 6th July it is cold at Kövecses and they don’t swim. ‘I painted a flower today. Love and heaps of kisses from Gisela.’

On Saturday 18th July mother and children return to Vienna from Kövecses. On Monday 20th July the British Ambassador, Sir Maurice de Bunsen, reports to Whitehall that the Russian Ambassador to Vienna has left for a fortnight’s holiday. That same day the Ephrussi leave for Switzerland: for their ‘long month’.

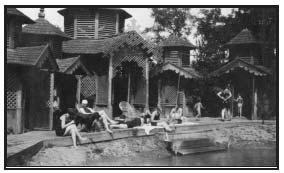

The bathing lake at Kövecses

The Russian imperial flag still flies from the boathouse roof. Viktor, worried that his son will grow up and have to do military service in Russia, has petitioned the Tsar to change his citizenship. This year Viktor has become a subject of His Majesty Franz Josef, the eighty-four-year-old Emperor of Austria, King of Hungary and Bohemia, King of Lombardy-Venetia, of Dalmatia, Croatia, Slavonia, Galicia, Lodomeria and Illyria, Grand Duke of Tuscany, King of Jerusalem and Duke of Auschwitz.

On 28th July Austria declares war on Serbia. On 29th July the Emperor declares: ‘I put my faith in my peoples, who have always gathered round my throne, in unity and loyalty, through every tempest, who have always been ready for the heaviest sacrifices for the honour, the majesty, the power of the Fatherland.’ On 1st August Germany declares war on Russia. On the 3rd Germany declares war on France, and then the following day invades neutral Belgium. And the whole pack of cards falls: alliances are invoked and Britain declares war on Germany. On 6th August Austria declares war on Russia.

Mobilisation letters are sent out in all the languages of the Empire from Vienna. Trains are requisitioned. All Jules and Fanny Ephrussi’s young French footmen, careful around the porcelain and good at rowing on the lake, are called up. The Ephrussi are stuck in the wrong country.

Emmy travels to Zurich to enlist the help of the Austrian Consul General, Theophil von Jäger – a lover of hers – to get the household back to Vienna. There are a lot of telegrams. Nannies, maids and trunks need sorting out. The trains are too crowded and there is too much luggage, and the railway timetable – the implacable

k & k

railway, as certain as Spanish court ritual, as regular as the Vienna City Corps marching past the nursery window at half-past ten every morning – is suddenly useless.

There is cruelty in all of this. The French, Austrian and German cousins, Russian citizens, English aunts, all the dreaded consanguinity, all the territoriality, all that nomadic lack of love of country, is consigned to sides. How many sides can one family be on at once? Uncle Pips is called up, handsome in his uniform with its astrakhan collar, to fight against his French and English cousins.

In Vienna there is fervent support for this war, this cleansing of the country of its apathy and stupor. The British ambassador notes that ‘the entire people and press clamour impatiently for immediate and condign punishment of the hated Serbian race’. Writers join in the excitement. Thomas Mann writes an essay ‘

Gedanken im Kriege

’, ‘Thanks Be for War’ the poet Rilke celebrates the resurrection of the Gods of War in his

Fünf Gesänge

; Hofmannsthal publishes a patriotic poem in the

Neue Freie Presse.

Schnitzler disagrees. He writes simply on 5th August: ‘World war. World ruin. Karl Kraus wishes the Emperor “a good end of the world”.’

Vienna was

en fête

: young men in twos and threes with sprigs of flowers in their hats on their way to recruit; military bands playing in the parks. The Jewish community in Vienna was cheerful. The monthly newsletter of the Austrian-Israelite Union, for July and August, declaimed: ‘In this hour of danger we consider ourselves to be fully entitled citizens of the state…We want to thank the Kaiser with the blood of our children and with our possessions for making us free; we want to prove to the state that we are its true citizens, as good as anyone…After this war, with all its horrors, there cannot be any more anti-Semitic agitation…we will be able to claim full equality.’ Germany would free the Jews.

Viktor thought otherwise. It was a suicidal catastrophe. He had dustsheets put over all the furniture in the Palais, sent the servants home on board wages, sent the family to the house of Gustav Springer, a friend, near Schönbrunn, then on to cousins in the mountains near Bad Ischl, and took himself to the Hotel Sacher to see out the war with his books on history. There is a bank to run, something that is difficult when you are at war with France (Ephrussi et Cie, rue de l’Arcade, Paris 8), England (Ephrussi and Co., King Street, London) and Russia (Efrussi, Petrograd).

‘This Empire’s had it,’ says the Count in Joseph Roth’s novel

The Radetzky March

:

As soon as the Emperor says goodnight, we’ll break up into a hundred pieces. The Balkans will be more powerful than we will. All the peoples will set up their own dirty little statelets, and even the Jews will proclaim a king in Palestine. Vienna stinks of the sweat of democrats, I can’t stand to be on the Ringstrasse any more…In the Burgtheater, they put on Jewish garbage, and they ennoble one Hungarian toilet-manufacturer a week. I tell you, gentlemen, unless we start shooting, it’s all up. In our lifetime, I tell you.

There were lots of proclamations that autumn in Vienna. Now that the war is properly under way, the Emperor addresses the children of his Empire. The newspapers print

‘Der Brief Sr. Majestät unseres allergnädigsten Kaisers Franz Josef I an die Kinder im Weltkriege’,

a letter from His Majesty, our all-loving Franz Josef I, to the children in the time of the World War: ‘You children are the jewels of all the peoples of mine, the blessing of their future conferred a thousand times.’

After six weeks Viktor realises the war is not going to end and returns from the Hotel Sacher. Emmy and the children are eventually brought back from Bad Ischl. The dustcovers are taken off the furniture. There is a lot of activity in the street outside the nursery window. There is so much noise from the demonstrating students – Musil notes ‘the ugliness of the singing in the cafés’ in his journal – from the marching soldiers, with their bands, that Emmy considers moving the children’s rooms altogether to a quieter part of the house. This does not happen. The house is poorly designed for families, she says – we are all on show here in one glass box, we might as well be living on the street itself, for all that your father does about it.

The students’ chants change week by week. They start with ‘

Serbien muss sterben!

’, ‘Serbia must die!’ Then the Russians get it: ‘One Round, One Russian!’ Then the French. And it gets more colourful by the week. Emmy is worried by the war of course, but she is also worried by the effect of all this shouting on the children. They have their meals now on a little table in the music room, which opens onto the Schottengasse and is a bit quieter.

Iggie attends the Schottengymnasium. This is a

very good school

run by the Benedictines round the corner, one of the

two best schools

in Vienna, he told me. The plaque on the wall that lists famous former poets indicates this. Though the teachers are Brothers, many of the pupils are Jewish. The school lays particular stress on the Classics, but there are also mathematics, algebra, calculus, history and geography classes. Languages are studied as well. Learning these is irrelevant for these three children, who switch between English and French with their mother and German with their father. They know only a smattering of Russian and No Yiddish. The children are told to speak only German outside the house. All foreign-sounding shops in Vienna have had their names pasted over by men on ladders.

Girls are not taught at the Schottengymnasium. Gisela is taught at home by her governess in the schoolroom, next to Emmy’s dressing-room. Elisabeth has negotiated with Viktor and now has a private tutor. Emmy is opposed to this. She is so angry about this inappropriate, complicated arrangement for her daughter that Iggie hears her shouting and then breaking something, possibly porcelain, in the salon. Elisabeth scrupulously follows the same curriculum as the one boys her age are taught at the Schotten - gymnasium, and is allowed to go to the school laboratory in the afternoons and have a lesson by herself with one of the teachers. She knows that if she wants to go to the university, then she has to pass the final examination from this school. Elisabeth has known since she was ten that she must get from this room, her schoolroom with its yellow carpet, across the Franzenring to that room, the lecture hall of the university. It is only 200 yards away – but for a girl, it might as well be a thousand miles. There are more than 9,000 students this year, and just 120 of them are female. You can’t see into the hall from Elisabeth’s room. I’ve tried. But you can see its window, and imagine the tiered seating and a professor leaning over the lectern at the front. He is talking to you. Your hand moves in a dream across your notes.

Iggie attends the Schottengymnasium reluctantly. You can run there in three minutes, though I haven’t tried this with a satchel. There is a class photograph from 1914, third form: thirty boys in grey-flannel suits with ties, or sailor suits, leaning on their desks. Two windows are open onto the five-storey central courtyard. There is one idiot pulling faces. The teacher is implacable at the back in his monastic robes. On the reverse of the photograph are all their signatures – all the Georgs, Fritzs, Ottos, Maxs, Oskars and Ernsts. Iggie has signed in a beautiful italic hand: Ignace v. Ephrussi.

On the back wall is a blackboard scrawled over with geometry proofs. Today they have been studying how to work out the surface area of a cone. Iggie comes home each day with homework. He detests it. He is poor at algebra and calculus and hates mathematics. Seventy years on, he could give me the names of each Brother and what they tried unsuccessfully to teach him.

And he comes home with rhymes:

Heil Wien! Heil Berlin!

In 14 Tagen

In Petersburg drinn’!

(Hail Vienna! Hail Berlin!

In 14 days

We’ll be in Petersburg!)

There are ruder ones than this. These do not go down well with Viktor, who loves St Petersburg and is Russian-born, though he is now, of course, Austrian and loves Vienna.

For Iggie, the war means playing soldiers. It is their cousin Piz – Marie-Louise von Motesiczky – who proves to be a particularly good soldier. There is a servants’ staircase in the corner of the Palais, tucked away behind a false door. It is a wide nautilus spiral of 136 steps that goes up to the roof and, if you pull the door towards you, then you are suddenly above the caryatids and acanthus leaves and you can see everything, the whole of Vienna. Turn slowly clockwise from the university, then the Votivkirche, then St Stephen’s, all the way back through the towers and domes of the Opera and Burgtheater and Rathaus to the university again. And you can dare each other to crawl right up to the edge of the parapet and peer down through the glass into the courtyard below, or you can shoot all the tiny scurrying burghers and their ladies in the Franzensring or in the Schottengasse. For this you use cherry stones and a roll of stiff paper and a good blow. There is a café directly below with wide canvas awnings, which is a particularly appealing target. The waiters in their black aprons look up and shout, and you have to dodge.