The Hare with Amber Eyes (11 page)

Read The Hare with Amber Eyes Online

Authors: Edmund de Waal

I try to map the straightforward correspondences that my Charles and the fictional Charles share, the lineaments of their lives. I say ‘straightforward’, but when I start to write them out they become quite a list.

They are both Jewish. They are both

mondain.

They have a social reach from royalty (Charles conducted Queen Victoria round Paris, Swann is a friend of the Prince of Wales) via the salons to the studios of artists. They are art-lovers deeply in love with the works of the Italian Renaissance, Giotto and Botticelli in particular. They are both experts in the arcane subject of Venetian fifteenth-century medallions. They are collectors, patrons of the Impressionists, incongruous in the sunshine at a boating-party of a painter-friend.

Both of them write monographs on art: Swann on Vermeer, my Charles on Dürer. They use their ‘erudition in matters of art…to advise society ladies what pictures to buy and how to decorate their houses’. Both Ephrussi and Swann are dandies and they are both Chevaliers of the

Légion d’honneur

. Their lives traverse

japonisme

and reach into the new taste for Empire. And they are both Dreyfusards who find that their carefully constructed lives are deeply riven by their Jewishness.

Proust played with the interpenetration of the real and the invented. His novels have a panoply of historical figures who appear as themselves – Mme Straus and the Princess Mathilde, for instance – mingling with characters reimagined from recognisable people. Elstir, the great painter who leaves behind his infatuation with

japonisme

to become an Impressionist, has elements of Whistler and Renoir in him, but has his own dynamic force. Similarly Proust’s characters stand in front of actual pictures. The visual texture of the novels is suffused not just with references to Giotto and Botticelli, Dürer and Vermeer, alongside Moreau, Monet and Renoir, but, by the act of looking at paintings, by the act of collecting them and remembering what it was to see something, with a memory of the moment of apprehension.

Swann catches resemblances in passing: Odette to a Botticelli, the profile of a footman at a reception to a Mantegna. And so did Charles. I cannot help wondering if my grandmother, so undishevelled, so very kempt in her white laundered frock on those gravel paths in the garden of the Swiss chalet, ever knew what made Charles bend down and ruffle her pretty sister’s hair and compare her to his Renoir of the gypsy girl?

And when I encounter Swann, he is funny and charming, but he has a quality of reserve ‘like a locked cabinet’. He moves through the world leaving people more alive to the things he loves. I think of how the young narrator, in love with Swann’s daughter, visits the household and is met with such courtesy, introduced to the sublimities of his collection.

That is my Charles, taking endless pains to show books or pictures to young friends, to Proust, writing about objects and sculpture with acuity and honesty, animating the world of things. I know. It is how I have come to see Berthe Morisot for the first time, how I learn to stand back and then move forward. It is how I have come to listen to Massenet, look at Savonnerie carpets, see that Japanese lacquer is worth spending time with. I pick up one after another of Charles’s netsuke and think of him choosing them. And I think of his reserve. He belongs in this glittering Parisian world, but he never stops being a Russian citizen. He always has this secret hinterland.

Charles had a poor heart like his father. He was fifty when Dreyfus was brought back from Devil’s Island to undergo his second farcical trial and be reconvicted in 1899. In the delicate engraving of him done in that year by Jean Patricot he is looking downwards, inwards, his beard still neatly trimmed, his cravat held by a pearl. He is more involved in music and is now a patron of the Comtesse Greffuhle’s Société des Grandes Auditions Musicales, ‘where his advice is greatly appreciated, and where he has put himself to work with ardour’. He had almost stopped buying pictures, except for a Monet of the rocks at low tide at Pourville-sur-Mer on the Normandy coast. It is a beautiful painting, scumbled rocks in the foreground and strange calligraphies of the fishermen’s wooden poles emerging from the sea. It is, I think, rather Japanese.

Engraving of Charles Ephrussi by Patricot published with his obituary in the

Gazette des beaux-arts

, 1905

Charles had slowed his writing too, though he was punctilious in his duties at the

Gazette

, clear about what should get published, ‘never ever late, ever diligent down to the very minutiae of every article, ever seeking perfection’, happy to bring on new writers.

Louise had a new lover. Charles was superseded by Crown Prince Alfonso of Spain, thirty years her junior and rather weak-chinned, but nonetheless a future king.

On the cusp of the new century, Charles’s first cousin in Vienna was to be married. Charles had known Viktor von Ephrussi since boyhood, when the whole family had lived together, all the generations under one roof, the evenings spent in planning their move to Paris. Viktor was the bored little boy, his youngest cousin, for whom Charles drew caricatures of the servants. The clan was close and they had seen each other at parties in Paris and Vienna, on holiday in Vichy and St Moritz, at Fanny’s summer gatherings at the Chalet Ephrussi. And they shared Odessa – the city they were both born in, the starting place that is not mentioned.

The three brothers in Paris all send a wedding-present to Viktor and his young bride, the Baroness Emmy Schey von Koromla. The couple will start their new life in the enormous Palais Ephrussi on the Ringstrasse.

Jules and Fanny send them a beautiful Louis XVI desk of marquetry with tapering legs ending in small gilt hooves.

Ignace sends them an Old Master painting, Dutch, of two ships in a gale. Perhaps a coded joke about marriage from a serial avoider of commitment.

Charles sends them something special, a spectacular something from Paris: a black vitrine with green velvet shelves, and a mirrored back that reflects 264 netsuke.

VIENNA 1899–1938

In March 1899, Charles’s generous wedding gift for Viktor and Emmy is carefully crated up and taken from the avenue d’Iéna, leaving the golden carpet, the Empire

fauteuils

and the Moreaus. It travels across Europe and is delivered to the Palais Ephrussi in Vienna, on the corner of the Ringstrasse and the Schottengasse.

It is time to stop walking with Charles and reading about Parisian interiors, and start reading the

Neue Freie Presse

and concentrating on Viennese street life at the turn of the century. It is October and I find I have spent almost a year with Charles – far longer than I thought possible, unwarranted skeins of time reading about the Dreyfus Affair. I do not have to move floors in the library: French literature and German literature are next to each other.

I am anxious about where my boxwood wolf and my ivory tiger are moving to. I book a ticket to Vienna and set out for the Palais Ephrussi.

This new home for the netsuke is absurdly big. It looks like a primer on classical architecture; it even makes the Paris houses of the Ephrussi look demure. The Palais has Corinthian pilasters and Doric columns, urns and architraves, four small towers at the corners, rows of caryatids holding up the roof. The first two storeys are powerfully rusticated, surmounted by two storeys of pale pink-washed brick, and stone behind the fifth-storey caryatids. There are so many of these massive, endlessly patient Greek girls in their half-slipped robes – thirteen down the long side of the Palais on the Schottengasse, six on the main Ringstrasse front – that they look a little as if they are lined up along a wall at a very poor dance. I cannot escape gold: there is lots of gilding to the capitals and balconies. There is even a name glittering across the façade, but this is comparatively new: the Palais is now the headquarters of Casinos Austria.

I do my house-watching here, too. Or, rather, I attempted to do my house-watching, but the Palais is now opposite a tram stop above an underground station pushing people out in a constant stream. There is nowhere that I can lean against a wall and pause and look. I try to place the roofline against the winter sky and almost walk into the path of a tram, and a bearded man in three coats and a balaclava harangues me for my carelessness, and I give him too much money to make him go away. The Palais is opposite the main building of the University of Vienna, where three campaigns of protest – American policies in the Middle East, carbon emissions, something to do with fees – compete for noise and signatures. It is an impossible place to stand.

The house is just too big to absorb, taking up too much space in this part of the city, too much sky. It is more of a fortress or a watch-tower than a house. I try to accommodate its size. It is certainly not a house for a wandering Jew. And then I drop my glasses and one of the arms fractures near the joint, so that I have to pinch them together to see anything at all.

I am in Vienna, 400 yards across a small park from the front door to Freud’s apartment, outside my paternal family house, and I cannot

see clearly

. Bring on the symbolism, I mutter, as I hold my glasses up to try and see this pink monolith; prove to me that this bit of my journey is going to be difficult. I am wrong-footed already.

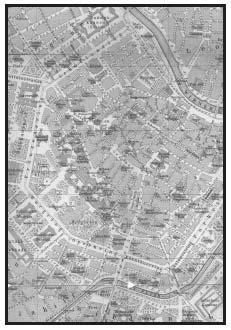

The Palais Ephrussi looking along the Schottengasse towards the Votivkirche, Vienna, 1881

So I go for a walk. I push my way through the students and I’m on the Ringstrasse, and I can move and can breathe.

Except that it is a windingly ambitious street, breath-catchingly imperial in scale. It is so big that a critic argued, when it was built, that it had created an entirely new neurosis, that of agoraphobia. How clever of the Viennese to invent a phobia for their new city.

The Emperor Franz Josef had ordered a modern metropolis to be created around Vienna. The old medieval city walls were to be demolished, the old moats filled in and a great arc of new buildings, a city hall, a Parliament, an opera house, a theatre, museums and a university constructed. This Ring would have its back to the old city and would look out into the future. It would be a ring around Vienna of civic and cultural magnificence, an Athens, an ideal efflorescence of

Prachtbauten

– buildings of splendour.

These buildings would be of different architectural styles, but the ensemble would pull together all this heterogeneity into a whole, the grandest public space in Europe, a ring of parks and open spaces; the Heldenplatz, the Burggarten and the Volksgarten would be ornamented with statues celebrating the triumphs of music and poetry and drama.

To produce this spectacle meant colossal engineering works. For twenty years it was dust, dust, dust. Vienna, said the writer Karl Kraus, was being ‘demolished into a great city’.

All the Emperor’s citizens from one end of the Empire to the other – Magyars, Croats, Poles, Czechs, Jews from Galicia and Trieste, all the twelve nationalities, the six official languages, the five religions – would encounter this

kaiserlich-königlich

, imperial and royal civilisation.

It works: I find that it is curiously difficult to stop on the Ring, with its endless deferred promise of a moment when you can see it all, together. This new street is not dominated by any one building; there is no crescendo towards a palace or a cathedral; but there is this constant triumphant pull along from one great aspect of civilised life to another. I keep thinking there will be one defining view through these bare winter trees, one framed moment glimpsed through my broken glasses. The wind sweeps me on.

I walk away from the university, built in its new Renaissance style, steps sweeping up to a great portico flanked by rows of arched windows, busts of scholars in every niche, classical sentinels on the rooftops, golden scrolls labelling anatomists, poets, philosophers.

I walk on past the Town Hall, fantasy Gothic, towards the bulk of the Opera, then past the museums and the Reichsrat, the Parliament, built by Theophilus Hansen, the architect of the moment. Hansen was a Dane who had made his name by studying classical archaeology in Athens and designing the Academy of Athens. Here, on the Ring, he built the Ringstrasse

Palais

for the Archduke Wilhelm, then the Musikverein, then the Academy of Fine Arts, then the Vienna Stock Exchange. And the Palais Ephrussi. He had won so many commissions by the 1880s that other architects suspected a conspiracy by Hansen and ‘his vassals…the Jews’.

It was no conspiracy. He was just very good at giving his clients what they wanted; his Reichsrat is one Greek detail after another. Birth of democracy, says the great portico. Protector of the city, says the statue of Athena. There is a little something everywhere you look to flatter the Viennese. There are chariots on the roof, I notice.

In fact, as I look up, I see figures everywhere against the sky.

On and on. It becomes a musical series of buildings, spaced with parks, punctuated by statues. It has a rhythm that suits its purpose. Ever since it was officially opened on 1st May 1865 with a procession by the Emperor and Empress, this had been a space for progresses, for display. The Hapsburg court lived according to Spanish court ceremonial, a severe code of ritual, and there were innumerable opportunities for complex court processions. And there was the daily marching of the City Regiment, and marches on major feast days of the Hungarian Guards, celebrations of the Imperial Birthday, jubilees, honour guards for the arrival of a Crown Princess, and funerals. All the guards had different uniforms: confections of sashes, fur trimmings and plumed hats and epaulettes. To be on the Vienna Ringstrasse was to be within earshot of a marching band, the drumming of feet. The Hapsburg regiments were the ‘best-dressed army in the world’, with a stage to match.

I realise that I am going too fast, walking as if I had a destination, rather than a point of departure. I remember that this was the street that was made for the slower movement of the daily ‘Korso’, the ritualised stroll for society along the Kärntner Ring to meet and flirt and gossip and be seen. In the illustrated scandal sheets that proliferated in Vienna around the time that Viktor and Emmy got married, there were often sketches showing ‘

ein corso Abenteuer

’, an adventure on the Corso, advances from bewhiskered men with canes or glances from

demi-mondaines

. There was a ‘regular jam’, wrote Felix Salten, ‘of knights of fashion, monocled nobles, members of the pressed-trouser brigade’.

This was a place to get dressed up for. In fact, it was the site of the most spectacular bit of dressing up in Vienna. In 1879, twenty years before Viktor and Emmy marry and Charles’s netsuke arrive, Hans Makart, a wildly popular painter of vast canvases of historical fantasy, orchestrated a

Festzug

or procession of artisans for the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Emperor’s wedding. The artisans of Vienna were deployed in forty-three guilds, each of which had its own float decorated in allegorical fashion. Musicians and heralds and pikemen and men with banners milled around each float. Everyone wore Renaissance costume, and Makart led the whole swaggering cavalcade on a white charger, wearing a wide-brimmed hat. It occurs to me that this slippage – a bit of Renaissance, a bit of Rubens, some cod-classicism – fits the Ringstrasse perfectly.

It is all so self-consciously grand, and yet a bit Cecil B. de Mille. I am the wrong audience for it. A young painter and architecture student, Adolf Hitler, had a proper visceral response to the Ringstrasse: ‘From morning until late at night I ran from one object of interest to another, but it was always the buildings that held my primary interest. For hours I could stand in front of the Opera, for hours I could gaze at the Parliament; the whole Ringstrasse seemed to me like an enchantment out of “The Thousand-and-One-Nights”.’ Hitler would paint all the great buildings on the Ring, the Burgtheater, Hansen’s Parliament, the two great buildings opposite the Palais Ephrussi, the university and the Votivkirche. Hitler appreciated how the space could be used for dramatic display. He understood all this ornament in a different way: it expressed ‘eternal values’.

All of this enchantment was paid for by selling building lots to the rapidly growing class of financiers and industrialists. Many of them were sold to create the Ringstrasse

Palais

, a type of building where a series of apartments lay behind one formidable façade. You could have the imposing

Palais

address, with a great front door and balconies and windows onto the Ringstrasse, a marble entrance hall, a salon with a painted ceiling-and yet live on just one floor. This floor, the

Nobelstock

, would have all the main reception rooms centred on a large ballroom. The

Nobelstock

is easy to spot as it has the most swags around its windows.

And because many of the inhabitants of these new

Palais

were the families who had recently made good, this meant that the Ringstrasse was substantially Jewish. Walking away from the

Palais

Ephrussi, I pass the

Palais

of the Liebens, the Todescos, the Königswaters, the Wertheims, the Gutmanns, the Epsteins, the Schey von Koromlas. These bravura buildings are a roll-call of inter-married Jewish families, an architectural parade of self-confident wealth where Jewishness and ornament were interlocked.

As I walk with the wind at my back, I think of my ‘vagabonding’ around the rue de Monceau and I remember Zola’s rapacious Saccard in his vulgarly opulent mansion, intrusive on the street. Here in Vienna there are subtly different arguments about the Jews of Zionstrasse behind the great façades of their

Palais

. Here, the common talk goes, the Jews had become so assimilated, had mimicked their Gentile neighbours so well, that they had tricked the Viennese and simply disappeared into the fabric of the Ring.

Robert Musil in his novel

The Man Without Qualities

has the old Count Leinsdorf muse on this disappearing act. These Jews have muddled social life in Vienna by not staying true to their decorative roots:

The whole so-called Jewish Question would disappear without a trace if the Jews would only make up their minds to speak Hebrew, go back to their old names, and wear Eastern dress…Frankly, a Galician Jew who has just recently made his fortune in Vienna doesn’t look right on the Esplanade at Ischl, wearing a Tyrolean costume with a chamois tuft on his hat. But put him in a long, flowing robe…Imagine them strolling along on our Ringstrasse, the only place in the world where you can see, in the midst of Western European elegance at its finest, a Mohammedan with his red fez, a Slovak in sheepskins, or a bare-legged Tyrolean.

Go into the slums of Vienna, Leopoldstadt, and you can see Jews living as Jews should live, twelve in a room, no water, loud on the streets, wearing the right robes, speaking the right argot. In 1863 when Viktor arrived in Vienna from Odessa as a three-year-old child, there were fewer than 8,000 Jews in Vienna. In 1867 the Emperor gave civic equality to Jews, removing the last barriers to their rights to teach and their ownership of property. By the time Viktor was thirty in 1890 there were 118,000 Jews in Vienna, many of the newcomers the

Ostjuden

driven out of Galicia by the horrors of the pogroms that had erupted throughout the previous decade. Jews also came from small villages in Bohemia, Moravia and Hungary, shtetls where their living conditions were abject. They spoke Yiddish and sometimes wore caftans: they were immersed in their Talmudic heritage. According to the popular Viennese press, these incomers were possibly involved in ritual murder, and certainly were involved in prostitution, hawking second-hand clothes, peddling goods all over the city with their strange baskets on their backs.