The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism (71 page)

Read The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism Online

Authors: Edward Baptist

Tags: #History, #United States, #General, #Social History, #Social Science, #Slavery

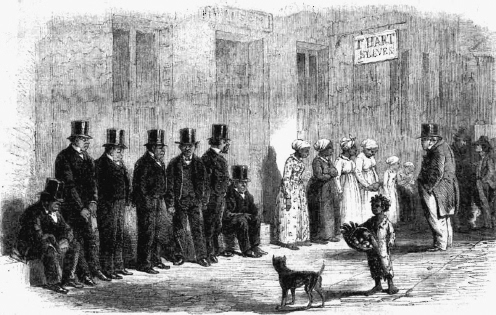

Image 10.1. Slave traders in New Orleans continued to receive and sell enslaved people whom they “packaged” as commodity “hands” in various ways—including by making them wear identical clothes.

Illustrated London News

, January—June 1861, vol. 38, p. 307.

Olmsted wrote four volumes about his journeys, relentlessly hammering home the argument that slavery’s inefficiency retarded southern

growth and national development. During the preceding decade, as slaveholders’ collective finances collapsed, educated northerners had concluded that this belief was a fundamental truth. Former Illinois congressman and lawyer Abraham Lincoln insisted that only “free labor gives hope to all, and energy, and progress, and openness of condition.” Lincoln himself had escaped unpaid toil in his father’s

muddy Indiana cornfields by walking to an Illinois frontier town, where he could work for a wage. On the way down to New Orleans, piloting his employer’s flatboats, he watched slaves toiling in the fields behind the delta levees. Returning to Illinois, he read law books, stood for elections, and turned himself into someone who hired other people.

8

Even though slavery supposedly undermined the

will to improve, northerners like Olmsted continually found southern whites pushing for efficiency.

“Time’s money, time’s money!” he heard a white man say on a Gulf steamboat. Pacing anxiously as enslaved and free Irish longshoremen loaded his cotton bales, the man worried about getting back to Texas in time for planting. The rush of the annual cotton cycle predisposed such men to feel tardy,

to push themselves to work harder at pushing other people harder. Yet maybe too much time had been lost in the 1840s, or maybe northern critics were right when they claimed that slaveholders had turned away from the path of progress, down some dead-end of history. Olmsted heard those questions lurking in conversations over dinner on steamboats. Southern whites raised such worries in a printed conversation

that filled newspapers and monthly journals, such as

DeBow’s Review

, published in New Orleans by James DeBow.

9

Ultimately, however, despite something of a northern consensus that slavery was backward and inefficient, and despite the hard times of the previous decade, plenty of southern readers and talkers answered the question of whether or not the South could continue to use slavery as its

recipe for modern economic development with a resounding

yes

. Take Josiah Nott, an Alabama racial theorist and a physician, who argued that mosquitoes, not swampy mists, transmitted malaria and yellow fever. In 1851, he wrote that “7,000,000 people” in the North, Britain, and France, “depend for their existence upon keeping employed the 3,000,000 negroes in the Southern states.” Emancipation would

be in such circumstances “the most stupendous example of human folly.” A “network of cotton” wove enslaved people into the web of “human progress,” and without their forced labor, it would unravel.

10

Over the decade, in fact, the ability of hands to undercut free and serf labor with ruthless efficiency reconfirmed the idea that whether or not Nott was right, Olmsted was wrong. In the hands of

cotton entrepreneurs, slavery was a highly efficient way to produce economic growth, both for white southerners and for others outside the region. In the 1850s, southern production of cotton doubled from 2 million to 4 million bales, with no sign of either slowing down or of quenching the industrial West’s thirst for raw materials. The world’s consumption of cotton grew from 1.5 billion to 2.5 billion

pounds, and at the end of the decade the hands of US fields were still picking two-thirds of all of it, and almost all of that which went to Western Europe’s factories. By 1860, the eight wealthiest states in the United States, ranked by wealth per white person, were South Carolina, Mississippi, Louisiana, Georgia, Connecticut, Alabama, Florida, and Texas—seven states created by cotton’s march

west and south, plus one that, as the most industrialized state in the Union, profited disproportionately from the gearing of northern factory equipment to the southwestern whipping-machine.

11

Although the whipping-machine could be astonishingly good at extracting productivity increases, some southern enslavers worried that dependence on world demand for cotton left the South vulnerable to two

dangers: first, to the global economy’s vagaries, and second, to a future in which the northern states’ immigration-driven population growth steadily sapped southern political power. Regional newspapers and magazines regularly featured articles arguing that the South should create a diversified economy that included a profitable factory sector, which could provide jobs that would attract white labor

to the South. In an 1855 issue of

DeBow’s Review

, for instance, William Gregg described his Graniteville, South Carolina, manufacturing complex, which he claimed was earning a profit of more than 11 percent. Others insisted that mining, iron-forging, and factory work could employ enslaved black labor. In quantitative terms, slave labor in southern factories produced as high a rate of net profit

as slave labor in the fields. It was also as productive as free labor in the Northeast. Slaves staffed most of the expanding iron foundries of Virginia. From the 1830s onward, industrial activity had increased significantly in the South, and enslaved labor was one reason why.

12

Industrially produced iron railroad tracks were redrawing the cotton frontier’s landscape. In the 1840s, southern railroads

had expanded from 683 miles in total length to 2,162 miles. But this increase was much lower than that in the free states, which in the same time period created a 7,000-mile network concentrated in the Northeast and Middle Atlantic states. During the 1850s, good times returned, and southern railroad construction projects increased the regional network there to 10,000 miles in length. Corners

of Alabama and Georgia, interior Florida, and East Texas had been too many days of wagon-hauling away from steamboat landings to become profitable cotton belts. But the railroads snaking up into hill counties made areas dominated by yeomen and poor whites ripe for transformation. Land speculation companies began to evict squatters. As total southern wealth increased, a new generation of poor whites

found themselves turned into unwanted drifters, despised and feared by planters moving into the new railroad-opened regions. When Olmsted visited Columbus, Georgia, men told him that the local textile factory’s 20,000 cotton spindles were tended by displaced “cracker girls,” whose jobs supposedly saved them from the temptations of prostitution. Southern factories would occupy whites newly forced

into landlessness, ameliorating the disruptive impact of the modern market on the Jeffersonian ideal of the independent small farmer as the backbone of the white republic.

13

Still, southern cotton planters realized that their own increased dependence on financial decisionmakers from outside their region was a thorny

problem. Financial collapses and the sovereign defaults that southwestern states

had executed during the era of repudiation made it impossible for would-be southern bankers to recapitalize themselves in the 1840s. But cotton demand began to climb again after 1848, leading to the longest period of high prices in the nineteenth century. Although southern state governments were rated as poor credit risks after their legislative repudiations, every year southern entrepreneurs

sold the vast majority of the world’s most widely traded commodity, so there was profit to be made from investing in the whipping-machine. Moreover, the 3.2 million people enslaved in the United States had a market value of $1.3 billion in 1850—one-fifth of the nation’s wealth and almost equal to the entire gross national product. They were more liquid than other forms of American property, even if

an acre of land couldn’t run away or kill an overseer with an axe.

14

Yet since the debt-and-repudiation crisis of the early 1840s, enslaved people were no longer being fully tapped as collateral by world financial markets. One untold story of US prosperity and global economic growth in the 1850s would be the creation of a new set of credit flows that used enslaved people’s bodies, lives, and

hands as the basis for lending in the cotton economy and profit-sharing by investors outside of it. This new financial ecology replaced the chaos of the 1840s, which in turn had succeeded the credit structures of the 1830s. In the 1830s, the securitization of mortgages on enslaved people through the medium of bonds sold on distant financial markets by planter-controlled, state-chartered banks had

dominated and organized the flow of credit into the southwestern cotton frontier. The new system of the 1850s would finance massive new expansions in the southwestern United States while also allowing world capital markets to take advantage of the massive collateral held by enslavers. But this new system would not give enslavers what they had lost with the panics of 1837 and 1839, and with repudiation,

and this was the control over the flow of credit and repayment that enslavers had once been able to exert.

The new financial ecology was brought into being by start-up firms launched by northerners with small amounts of capital, who moved to southern ports in the wake of 1839 to buy cotton. These were companies such as, for instance, Lehman Brothers of Mobile, Alabama. In the disrupted environment

left by the destruction of the old mercantile firms, these new organisms acquired an old name, “factor,” which had a long history in the Atlantic slave trade, and their role in the cotton economy evolved quickly. They began to lend money to enslavers on the security of ensuing crops and mortgages on slaves. Factors also arranged for transportation, secured insurance for crops

in transit, and bought

supplies for clients’ labor camps. Any collection of mid-nineteenth-century personal and business documents from the South will be stuffed with the account sheets generated by factors, blue paper, covered in ferrous ink dried to rusty red and black. By the mid-1850s, the hinterland of every cotton port had several large firms—such as Buckner, Stanton, and Co., of New Orleans—standing head and

shoulders above the rest.

15

In the 1850s, the factor mediated between cotton producers and the world market, channeling credit and taking the immediate risk of lending. The factors themselves needed credit, and their financing came from New York banks, such as Brown Brothers. Factors alone could not satisfy all the borrowing needed to generate a cotton crop that increased in total value 450 percent

between 1840 and 1859. The lenders depended on personal relationships that allowed them to evaluate the creditworthiness of potential borrowers, so small-scale cotton producers were often kept on a short tether, when they could get tied in at all. Bigger planters and small-town merchants found that they could take their own incoming flow of credit from factors, repackage it, and pass it on

at more capillary levels, thus making money from their own investments in other people’s enslavement of still other people. Thus, $1 lent by Philadelphia-based factor Washington Jackson became $2 lent by Natchez megaplanter Stephen Duncan to his neighbors. Repackagers usually demanded a mortgage on individual slaves as security, and as locally powerful residents, they were in a position to enforce

this requirement. While slave mortgages had been made since the seventeenth century, they now became ubiquitous. During 1859, Louisiana enslavers raised $25.7 million, 75 percent of the value of cotton produced in the state that year, by mortgaging slaves.

16

The world market’s willingness to lend reveals its continued faith in the long-term profitability of slavery. The new system of credit delivery

was capillary, as opposed to the arterial system of the 1830s, and so defaults and other breaks in its flow were less catastrophic. It certainly profited lenders up and down the chain, even the little old ladies in Mayfair townhouses who let London men of business put their inheritances into the hands of other men of business. Passing through a chain of intermediaries, that money would be

lent on a slave in Mississippi, usually generating 8 percent interest, the highest allowed in many states that had passed usury laws. The collateral of enslaved bodies profited investors around the globe once again in the 1850s. But the new system also connected each borrower to the world economy primarily as an indebted individual property owner, rather than as a member of a unified group controlling

a bond-issuing state as sovereign citizens, and a

state bank as stockholders, as had been the case in the 1830s. The disempowering experience of mortgaging without local control over the entrance and exit of credit into statewide economies might have increased enslavers’ receptivity to the Calhounian substantive-due-process doctrine. And so southern public intellectuals’ cries for diversification

were not just about where one’s shoes were made (Massachusetts), but about where one’s credit came from, and where one’s interest charges went (London, New York).