The Gunpowder Plot: Terror & Faith in 1605 (2 page)

Read The Gunpowder Plot: Terror & Faith in 1605 Online

Authors: Antonia Fraser

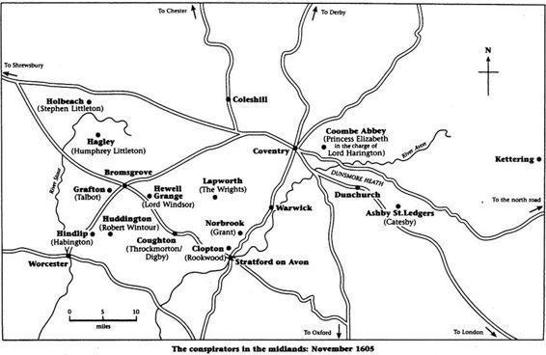

Map of the conspirators in the Midlands

‘That heavy and doleful tragedy which is commonly called the Powder Treason’: thus Sir Edward Coke, as prosecuting counsel, described the Gunpowder Plot of 1605. It is a fair description of one of the most memorable events in English history, which is celebrated annually in that chant of ‘Remember, remember the Fifth of November’. But who was the Gunpowder Plot a tragedy for? For King and Royal Family, for Parliament, all threatened with extinction by terrorist explosion? Or for the reckless Catholic conspirators and the entire Catholic community, including priests, whose fate was bound up with theirs? In part, this book attempts to answer that question.

Its primary purpose is, however, to explain, so far as is possible in view of imperfect records and testimonies taken under torture, why there was a Gunpowder Plot in the first place. The complicated details of this extraordinary episode resemble those of a detective story (including an anonymous letter delivered under cover of darkness), and, as in all mysteries, the underlying motivation is at the heart of the matter.

Obviously, to talk of providing an explanation begs the question of whether there really was a Plot. Over the years – over the centuries – dedicated scholars and historians have divided into two categories on the subject. I have lightly designated these ‘Pro-Plotters’ – those who believe firmly in the Plot’s existence – and ‘No-Plotters’ – those who believe equally firmly that the Plot was a fabrication on the part of the government. My own position, as will be seen, does not fall precisely into either of these categories. I believe that there was indeed a Gunpowder Plot: but it was a very different ‘Powder Treason’ from that conspiracy outlined by Sir Edward Coke.

By accepting that there was a Plot, I have also accepted that the conspirators were what we would now term terrorists. Certainly, the questionable moral basis for terrorism – can violence ever be justified whatever the persecution, whatever the provocation? – is a theme which runs through my narrative. And there is an additional problem: is terrorism justified only when it is successful? These are awkward questions, but for that reason, if no other, worth the asking.

Writers on the subject of the Plot have, naturally enough, tended to draw their own contemporary comparisons. A student of Catesby family history in 1909 referred to ‘these days of [Russian] Anarchist plots’ as providing a suitable background for Catesby’s own conspiratorial activities. Donald Carswell, a barrister who edited

The Trial of Guy Fawkes

in 1934, likened the Gunpowder Plot to the Reichstag Fire of February 1933: ‘it turned out to be first-class government propaganda’, enabling the Nazis to suppress the Communists, as the Catholics had been suppressed after 1605.

Graham Greene, providing an introduction in 1968 to the memoirs of Kim Philby, the Briton who spied for Stalin’s Russia, compared Philby’s Communist faith – ‘his chilling certainty in the correctness of his judgment’ – to that of the English recusant Catholics, supporting Spain and its Inquisition. Elliot Rose, in

Cases of Conscience,

published in 1975, the year in which the Vietnam War ended, drew a parallel between Catholics who refused to conform in the reign of Elizabeth and James I, and protesters against the Vietnam War. More recently, Gary Wills in

Witches and Jesuits: Shakespeare’s Macbeth

(1995) evoked the turbulent conspiratorial atmosphere in the United States after the assassination of President Kennedy to explain the world in which the play first appeared. (First performed in 1606, the text of

Macbeth

is darkened by the shadow of the Gunpowder Plot.) Certainly, the events of 5 November 1605 have much in common with the killing of President Kennedy as a topic which is, in conspiratorial terms, eternally debatable.

It is appropriate, therefore, that in my case a book written towards the end of the twentieth century should be concerned with the issue of terrorism. This is an issue, for better or for worse, which has to be considered in order to understand the unfolding histories of Northern Ireland and Israel/Palestine – to take only two possible examples. Meanwhile we have a phenomenon in which a number of today’s world leaders have in the past been involved – on their own recognition – in terrorist activities and have morally justified them on grounds of national or religious interest. It is for this reason I have given my book the subtitle of

Terror and Faith in 1605.

One should, however, bear in mind that the word ‘terror’ can refer to two different kinds. There is the terror of partisans, of freedom fighters, or of any other guerrilla group, carried out for the higher good of their objectives. Then there is the terror of governments, directed towards dissident minorities. The problem of subjects who differ from their rulers in religion (have they the moral right to differ?) is one that runs throughout this book.

There is a similar contemporary relevance of a very different sort in the stories of the various Catholic women who found themselves featuring in the subterranean world of the Gunpowder Plot. At a time when women’s role in the Christian Churches, especially the Catholic Church, is under debate, I was both interested and attracted by the role played by these strong, devout, courageous women. At the time Catholic priests compared them to the holy women of the Bible who followed Jesus Christ. Some were married with the responsibilities of families in a dangerous age; others chose the single path with equal bravery. Ironically enough, it was the perceived weakness of women which enabled them to protect the forbidden priests where others could not do so. Circumstances gave them power; they used it well.

Above all, throughout my narrative, I have been concerned to convey actuality: that is to say, a sense of what an extraordinarily dramatic story it was, with all its elements of tragedy, brutality, heroism – and even, occasionally and unexpectedly, its more relaxed moments, which sometimes occurred after unsuccessful searches for Catholic priests in their hiding-places. For this reason I have paid special attention to the topography of the Plot, including the details of these secret refuges, many of which are still to be seen today. Of course hindsight can never be avoided altogether, especially in untangling such an intricate story as that of the Gunpowder Plot: but at least I have tried to write as though what happened on 5 November 1605 was not a foregone conclusion.

In order to tell a complicated story as clearly as possible, I have employed the usual expedients. I have modernised spelling where necessary, and dated letters and documents as though the calendar year began on I January as it does now, instead of 25 March, as it did then. I have also tried to solve the problem of individuals changing their names (on receipt of titles) by preferring simplicity to strict chronological accuracy: thus Robert Cecil, 1st Earl of Salisbury, is known as Cecil and then Salisbury, missing out his intermediate title of Viscount Cranborne.

In writing this book, I owe a great deal to the many works of the many scholars acknowledged in the References. For further assistance, I would like to single out and thank the following: Mr Felipe Fernandez-Armesto for historical corrections and suggestions (surviving errors are my responsibility); Dr S. Bull, Lancashire County Museums, for allowing me to read his thesis ‘Furie of the Ordnance’; Fr Michael Campbell Johnston S.J. for letting me see the Gunpowder Plot MS. of the late Fr William Webb S.J.; Dr Angus Constam of the Royal Armouries; Fr Francis Edwards S.J., whose friendship and support I value, despite our different conclusions on the subject of the Gunpowder Plot; Mr D.L. Jones, Librarian, House of Lords; Mr John V. Mitchell, Archivist, and Mr R.N. Pittman, then headmaster of St Peter’s School, York; Mr Roland Quinault, Honorary Secretary, Royal Historical Society, for allowing me to consult his thesis, ‘Warwickshire Landowners and Parliamentary Politics 1841–1923’; Mr Richard Rose, editor of the unpublished diary of Joan Courthope; Mr M.N. Webb, Assistant Librarian, Bodleian Library; Mr Eric Wright, Principal Assistant County Librarian, Education and Libraries, Northamptonshire; lastly the ever helpful and courteous staff of the Catholic Central Library, the London Library, the Public Record Office and the Round Reading Room of the British Library.

It was, as ever, both a pleasure and a privilege to do all my own research, beyond the help which is gratefully acknowledged here. In particular, tracing the story of the Gunpowder Plot involved me in a series of historical visits and journeys. In connection with these, I wish to thank the Earl of Airlie, Lord Chamberlain, General Sir Edward Jones, Gentleman Usher of the Black Rod, and Mr Bryan Sewell, Deputy Director of Works, for making possible a visit to the House of Lords on the eve of the Opening of Parliament; Mr R. C. Catesby for our journey to Ashby St Ledgers and its church; Professor Hugh and Mrs Eileen Edmondson of Huddington Court for their hospitality; Mr and Mrs Jens Pilo for receiving me at Coldham Hall, and Mr Tony Garrett, who accompanied me there; Mr Roy Tomlin, Honorary Secretary, Wellingborough Golf Club, Harrowden Hall; Sr Juliana Way, Hengrave Hall Centre; Mr Dave Wood, Service Coordinator, and Mr David Hussey, Headmaster, RNIB Forest House Assessment Centre, Rushton.

Others who helped me in a variety of ways were Mrs K. H. Atkins, Archivist, Dudley Libraries; Professor Karl Bottigheimer; Mr Robert Bearman, Senior Archivist, Shakespeare Birthplace Trust; Mr Roy Bernard, Holbeche House Nursing Home; Fr Andrew Beer, St Pancras Church, Lewes; Fr M. Bossy, S.J., for the photograph of Helena Wintour’s vestment at Stonyhurst; Mr Conall Boyle; Mrs Kathryn Christenson, Minnesota; Mr Donald K. Clark, Director, Hyde Park Family History Centre; Ms Sarah Costley, then Archivist, York Minster, and Mr John Tilsley, Assistant Archivist; Ms Caroline Dalton, Archivist, New College Library; Mr Charles Enderby; Mr Dudley Fishburn M.P.; Major-General G.W. Field, Resident-Governor, Catherine Campbell, and Yeoman Warder Brian A. Harrison, Honorary Archivist, Tower of London; Ms Joanna Grindle, Information Officer, Warwickshire County Council; Father D.B. Lordan, St Winifred’s Church, and Brother Stephen de Kerdrel, O.P.M. Cap, Franciscan Friary, Pantasaph, Holywell; the Very Rev. Michael Mayne, Dean of Westminster; Mr Jonathan Marsden, Historic Buildings Representative, Thames and Chilterns Regional Office, National Trust; Professor Maurice Lee, Jr; Mr Stephen Logan, Selwyn College, Cambridge; Miss K.M. Longley, former Archivist, York Minster; Mr Roger Longrigg for answering an enquiry about late-sixteenth-century horses; Mother John Baptist, O.S.B., Tyburn Convent; Mr Simon O’Halloran, Queensland, Australia; Sir Roy Strong; Mr Barry T. Turner, Guy Fawkes House, Dunchurch; Mrs Clare Throckmorton, Coughton Court; Mr Richard Thurlow, National Bibliographic Service, British Library, Boston Spa; Mr J. M. Waterson, Regional Director, East Anglia Regional Office, National Trust; Mr Ralph B. Weller.

Throughout, I have had great support from my publishers on both sides of the Atlantic: Nan Talese in the US, who, from the first, shared my vision of how the book might be; and Anthony Cheetham, Ion Trewin and Rebecca Wilson in England. Linda Peskin typed and retyped the MS with exemplary skill, matched only by her patience. My agent Michael Shaw counselled calm at the appropriate moments; Douglas Matthews, Indexer Extraordinary, not only performed his task with his accustomed dexterity but also supplied information about Guy Fawkes ‘celebrations’ in Lewes; Robert Gottlieb and Rana Kabbani offered editorial suggestions, as did my mother, Elizabeth Longford. Further family assistance included advice on the modern Prevention of Terrorism Act from my son-in-law Edward Fitzgerald Q.C. and my son Orlando Fraser. Lastly my husband Harold Pinter read a story which is, in part, about persecution, with his characteristic generous sympathy for the oppressed.