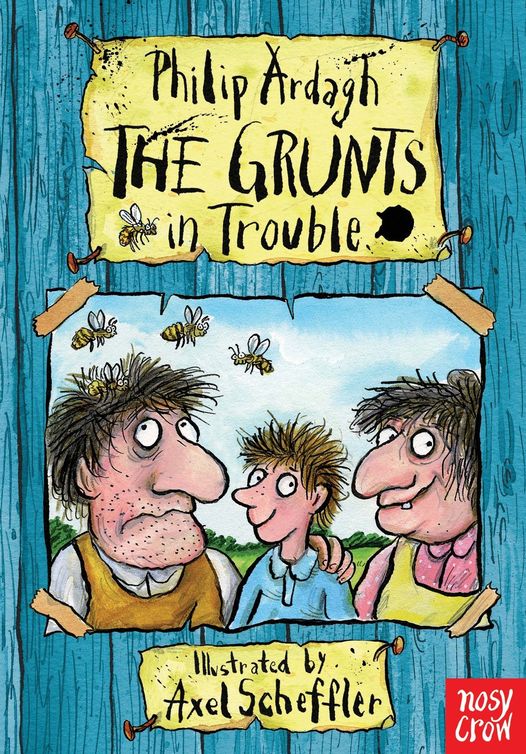

The Grunts In Trouble

Read The Grunts In Trouble Online

Authors: Philip Ardagh

For FCRC,

with thanks for his permission

to use the name “Ginger Biscuit”

Chapter One

M

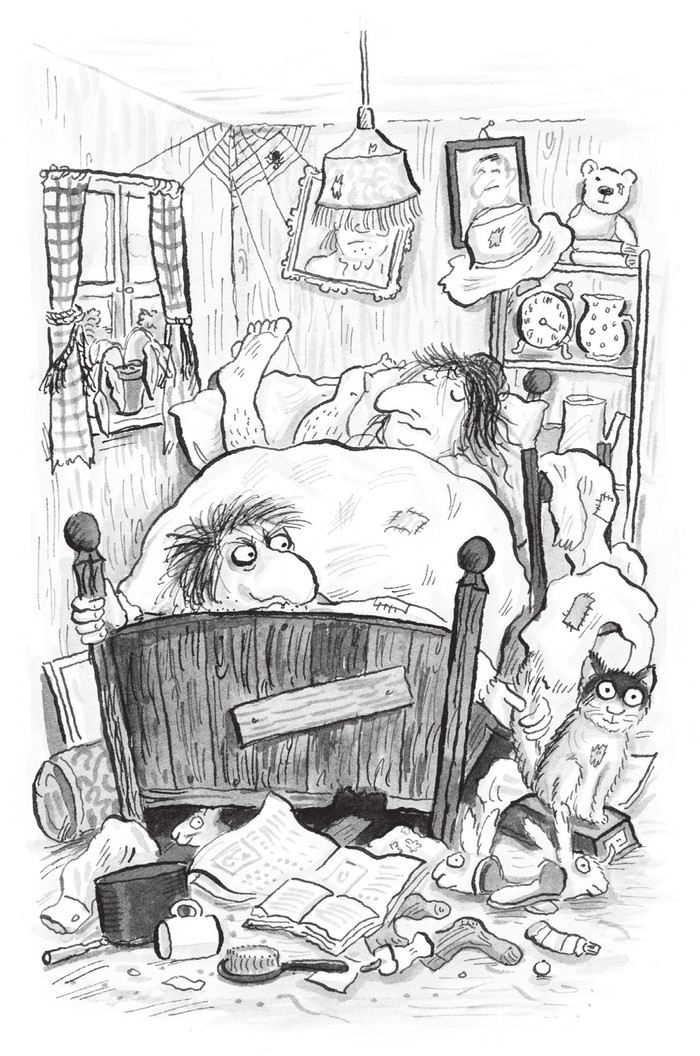

r Grunt woke up with his head down by the footboard and his feet up by the headboard. He didn’t realise that he’d got into bed the wrong way round the night before, so he thought someone had turned the room round in the night. And who did he blame? His wife, Mrs Grunt, of course.

Mr Grunt was FUMING. He reached over the side of the bed and, feeling something fluffy and stiff, curled his hairy fat fingers around it. It was Ginger Biscuit’s tail. Ginger Biscuit wasn’t a biscuit and, although he was great-big-ginger-cat-shaped, he wasn’t a great big ginger cat either. Ginger Biscuit was a doorstop: a doorstop stuffed with sawdust and

very heavy

(as doorstops should be). Mrs Grunt loved that old cloth moggy so much that she made Mr Grunt stuff him with fresh sawdust every time he sprung a serious leak. (Whenever Mr Grunt refused, she hid his favourite hat in the back of the fridge until he did.)

Mr Grunt struggled out of bed and stomped over to the window, accidentally brushing Ginger Biscuit’s tail against Mrs Grunt’s nose. She was snoring like an old boiler about to break down any minute, and had her mouth half open showing a jumble of yellow and green teeth. “Wh— What?” she spluttered, sitting up with a jolt. “What are you playing

at, mister?”

“Teaching you a lesson, wife!” grunted Mr Grunt, opening the window and throwing the stuffed cat straight out of it.

Mrs Grunt watched it go with a mixture of puzzlement and anger. “Lesson? What lesson?” she demanded. (She had hated lessons at school, except for science when she could make explosions – she

loved

a good explosion – and certainly didn’t want Mr Grunt teaching her a lesson first thing in the morning.) She swung her legs over the side of the bed and rammed her feet into a moth-eaten pair of old bunny slippers.

“I can’t remember what lesson!” said Mr Grunt, which was true. He couldn’t. “I want

my breakfast.”

(I don’t usually eat breakfast myself, but there are those people who say that it’s the most important meal of the day. One thing you can be sure of, though, is that people who say that about breakfast have

never

eaten one of the Grunts’ breakfasts.)

Mrs Grunt snorted. “Then MAKE some breakfast,” she said.

“But it’s your turn!” Mr Grunt insisted. “I made us that lovely badger porridge yesterday morning.” (The Grunts usually made meals from things they found squashed in the road. Squashed squirrels were a favourite, but even old car tyres didn’t taste too bad to them, if they added enough salt and pepper.)

“It was badger STEW, not porridge,” grunted

Mrs Grunt, “and you made it for

lunch

not breakfast, so it’s YOUR TURN.”

“Huh!” grunted Mr Grunt grudgingly. Mrs Grunt was right. He could now remember the bird-seed-and-sawdust cereal she’d served up the previous morning. Not bad. Not bad at all. He watched her stomping off in those tatty old bunny slippers of hers. She looked beautiful. Well, she looked beautiful to

him

. “Where are you going?” he demanded.

“I’ve got a cat to collect,” said Mrs Grunt. She stepped out of the bedroom, tripped over something on the landing and promptly fell down the stairs.

The something she’d tripped over was Sunny. Sunny wasn’t the Grunts’ flesh-and-blood child. They didn’t have one of their own, but Mrs Grunt had always wanted one and on one of those rare occasions when Mr Grunt was in a good mood and feeling all lovey-dovey towards his wife, he’d got her

one. Well,

stolen

one. (Not that he’d planned it, you understand. Oh no, it wasn’t planned. It kind of just

happened

.)

Mr Grunt had been out pounding the pavement in search of something else – I’ve no idea what – when he’d glanced over a garden wall (or maybe a fence, he could never remember which) and caught sight of a washing line. On that washing line had been an assortment of things hanging up to dry, one of which he was pretty sure was a spotted sock and another of which had been a child. The child was held in position by large, old-fashioned clothes pegs clipped to each ear. And before you could say, “Put that child back, it’s not yours … and, anyway, it’s not dry yet!” Mr Grunt had leaned over the wall (or fence) and whipped that child off the line.

Mrs Grunt had been very pleased. Sunny

was the best present Mr Grunt had ever given her (with the possible exception of a pair of very expensive gold-coloured sandals and some old taped-together barbecue tongs, which she used to pull out her nose hairs). Mrs Grunt didn’t know much about children but she could tell this one was a boy.

Mrs Grunt knew that boys should always be dressed in blue so she took a bottle of blue ink out of Mr Grunt’s desk and tipped the contents into a great big saucepan full of boiling water. Next, she found some of her old dresses back from when she was a little girl and added them to the mix. She’d kept the dresses to use as cleaning rags, but now they were dyed they didn’t look bad. Then, because she didn’t like to waste things, she went on to serve up the boiling blue water to Mr Grunt, who’d liked it so much he had seconds. But he wasn’t so

happy when he had a blue tongue and blue lips for eight weeks.

Sunny was already an odd-looking boy, what with his left ear being higher than his right ear and that kind of sticky-up hair which NEVER goes flat, even if you pour glue into it and then try taping it into position with rolls of sticky tape, but in a badly made, badly dyed blue dress he looked really, REALLY odd.

Here, let me spell that for you:

(Perhaps you could jot it down on a piece of paper and keep it under your beard until I ask you for it later. If you don’t have a beard

then perhaps you could ask for one for your birthday.)

Sunny had been very young when Mr Grunt had snatched him from that washing line, so he didn’t remember much about his real parents. He couldn’t remember his father at all (though he did have a memory of a pair of amazingly shiny polished black shoes). As for his mother, what he seemed to remember most about her was a nice warm snuggly feeling and the smell of talcum powder. Once in a while, snatches of a song would drift into his mind on little wisps of memory. The song was something to do with fluffy little lambs shaking their lovely little lambs’ tails, and – in his mind – it was his mother singing it. She had the voice of an angel who’d had singing lessons from a really good teacher.