The Great War for Civilisation (37 page)

CHAPTER SIX

“The Whirlwind War”

GAS! GAS! Quick, boys!âAn ecstasy of fumbling,

Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time;

But someone still was yelling out and stumbling

And flound'ring like a man in fire or lime . . .

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,

Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues . . .

âWilfred Owen, “Dulce et Decorum Est”

SADDAM HUSSEIN CALLED IT “The Whirlwind War.” That's why the Iraqis wanted us there. They were victorious before they had won, they were celebrating before they had achieved success. Saad Bazzaz at the Iraqi embassy in London couldn't wait to issue my visa and, after flying from Beirut to LondonâMiddle East journalism often involves vast round-trips of thousands of kilometres to facilitate a journey only a few hundred kilometres from the starting pointâI was crammed into the visa office with Gavin Hewitt of the BBC and his crew and more radio and newspaper reporters than I have ever seen in a smoke-filled room before. We would fly to Kuwait. We would be taken from there across the Iraqi border to the war front at Basra. And so we were. In September 1980 we entered Basra at night in a fleet of Iraqi embassy cars from Kuwait City, the sky lit up by a thousand tracer shells. Jets moaned overhead and the lights had been turned off across the city, a blackout to protect all of us from the air raids.

“Out of the cars,” the Iraqis shouted, and we leapt from their limousines, crouched on the pavements, hands holding microphones up into the hot darkness as the frail Basra villas, illuminated by the thin moonlight around us, vibrated to the sound of anti-aircraft artillery. The tracer streaked upwards in curtains, golden lines that disappeared into the smoke drifting over Basra. Sirens bawled like crazed geriatrics and behind the din we could hear the whisper of Iranian jets. A great fire burned out of control far to the east, beyond the unseen Shatt al-Arab River. Gavin, with whom I had shared most of my adventures in Afghanistan that very same year, was standing, hands on hips, in the roadway. “Jesus Christ!” he kept saying. “What a story!” And it was. Never again would an Arab army so welcome journalists to a battle front, give them so much freedom, encourage them to run and take cover and advance with their soldiers. In the steamy entrance of the Hamdan Hotelâthe authorities had switched off power across Basra and the air conditioners were no longer workingâthe staff had turned on their battery-powered radios. There was a constant blowsy song, all trumpets and drums and men's shouting voices.

Al-harb al-khatifa, nachnu nurbah al-harb al-khatifa

. “The whirlwind war, the whirlwind war, we shall win the whirlwind war,” they kept chanting.

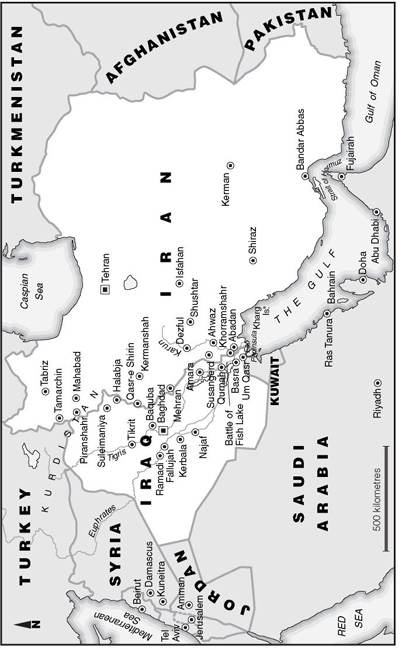

We stood on the steps, watching the spray of pink and golden bullets ascending into the dark clouds that scudded across Basra. Somewhere to the east of the city, through the palm groves on the eastern banks of the Shatt al-Arab and all the way to the north, Saddam's army was moving eastwards through the night, into Iran, into the great deserts of Ahwaz, into the Kurdish mountains towards Mahabad. The Arab journalists who had accompanied us up from Basra were ecstatic. The Iraqis would win, the Iraqis would protect the Arab world from the threat of Iran's revolution. Saddam was a strong man, a great man, a good man. They were confident of his victoryâeven more confident, perhaps, than Saddam himself.

Yet the orders to give us journalists the freedom of the battlefield must have come from Saddam. We could take taxis without the usual “minders,” all the way to the front if we wanted. The Ministry of Information would provide us with officials to escort us through road checkpoints if we wished. The Fao peninsula, that vulnerable spit of land south of Basra from which you can look eastwards across “the Shatt” at the palm-fringed shore of Iran? No problem. But when we reached Fao, it was under constant Iranian shellfire and the two deep-sea oil terminals 30 kilometres off the coast, Khor al-Amaya and Mina al-Bakrâthe latter, one of the most modern in the world, had been opened only four years earlierâwere already seriously damaged by Iranian ground-to-ground missiles. The Iraqis had not been able to silence the Iranian guns.

By 29 September 1980, exactly a week after the Iraqi invasion, Iranian shells were landing around Fao at the rate of one every twenty-five seconds and it was unsafe even to drive along the river promenade. The windows and doors of houses in the city rattled as each round exploded, hissing over the bazaar and crashing beyond the oil storage depots. In revenge, the Iraqis had attacked the huge oil terminal at Abadan, and for more than an hour I sat near the river, watching 200-metre gouts of fire shooting into the air over Abadan, a ripple of flame that moved with frightening speed along the bank of the river beneath a canopy of black smoke. An Iraqi official crouched next to me, pointing out the Iranian positions on the other shore. So much for the claims on Iraqi radio that its army had “surrounded” Abadan. In Basra, two Iranian Phantoms bombed a ship moored in the river, setting it on fire and splattering bullets along the waterfront walls, proof that the Iranian air force was still capable of daylight raids.

The Iraqis claimed to have shot down four Phantoms in five days, and the undamaged fuel tank of one aircraftâthe American refuelling instructions still clearly readable on one canister in a local Baath party headquartersâwas proof that their claim was at least partly true. The Iranians had damaged homes and schools in Faoâthough their pilots could hardly be expected to distinguish between “military” and “civilian” targets during their high-speed low-level attacks.

Fao was almost deserted. I watched many of its inhabitantsâpart of the constant flow of millions of refugees which are part of Middle East historyâdriving north-west to Basra in a convoy of old wooden Chevrolet taxis, bedding piled on the roofs and chador-clad mothers and wives on the back seats, scarcely bothering to glance at the burning refineries of Abadan. They were Iraqi Shia Muslims and now they were under fire from their fellow Shias in Iran, another gift from Saddam.

Already I was beginning to realise that this war might not be so easy to win as the Iraqi authorities would have us believe. In Washington and London, the usual military “experts” and fossilised ex-generals were holding forth on the high quality of the Iraqi army, the shambles of post-revolutionary Iran, the extraordinary firepower of Iraq's largely Soviet equipped forces. But on 30 September, eight days after their invasion, the Iraqis could only claim that they were 15 kilometres from Khorramshahrâthe old Abbasid harbour which was Iran's largest port, and closer than “surrounded” Abadan.

I crossed the river from Basra, trailing behind convoys of military trucks carrying bridge-building equipmentâthe Iraqis had yet to cross the Iranian Karun River north of Khorramshahrâand headed into the blistering, white desert towards the Iranian border post at Shalamcheh. I overtook dozens of T-62 tanks and Russian-made armour and trucks piled with soldiers, all of whom obligingly gave us two-finger victory signs. The air thumped with the sound of heavy artillery, and on a little hill in the desert I came across the wrecked Iranian frontier station, stopped the car and gingerly walked inside. I was in Iran, occupied Iran. No problem with visas now, I thought. It's always an obscure thrill to enter a country with an invading army, knowing how furious all those pious little visa officers would beâthose who kept me waiting for hours in boiling, tiny rooms, the perspiration crawling through my hairâif they could see me crossing their borders without their wretched, indecipherable stamps in my passport. Pictures of Ayatollah Khomeini had been ritually defaced on the walls of the Shalamcheh frontier station and a large pile of handwritten ledgers were strewn over the floor.

I have a fascination for the documents that blow through the ruins of war, the pages of letters home and the bureaucracy of armies and the now useless instructions on how to fire ground-to-air missiles that flutter across the desert and cover the floors of roofless factories. These books were written in Persian and recorded the names and car numbers of Iraqis and Iranians crossing the border at Shalamcheh. The last entry was on 21 September 1980, just a day before the Iraqi invasion. So although the Iraqis claimed that the war began on 4 September, they had allowed travellersâincluding their own citizensâto transit the border quite routinely until the very eve of their invasion.

An American camera-crew had pulled up outside the wreckage of the building and were dutifully filming the desecrated pictures of Khomeini, their reporter already practising his “stand-upper.” “Iraq's army smashed its way across the Iranian frontier more than a week ago and now stands poised outside the strategic cities of Khorramshahr and Abadan . . .” Yes, cities were always “strategic”âat least, they always were on televisionâand armies must always “smash” through borders and stand “poised” outside cities. It was as if there was only one script for each event. Soon, no doubt, the Iraqis would be “fighting their way” towards Khorramshahr, or “poised” to enter Khorramshahr, or “claiming victory” over the Iranian defenders.

But who was I to talk? My CBC tape recorder hung over my shoulder and behind the border post stood a battery of Russian 155-mm guns, big beasts whose barrels pointed towards Khorramshahr and whose artillery captain walked up to us smiling and asked politely if we would like his guns to open fire. For a millisecond, for just that little fraction of temptation, I wanted to agree, to say yes, I would like them to fire, just the moment I had finished adjusting my microphone; and the captain was already turning to give the order to fire when a moral voice shouted at meâI had just imagined the tearing apart of an unknown bodyâand I ran after him and said, no, no, he should not fire, not for me, not under any circumstances.

But of course, I found a basin in the sand and sat down in it and leaned on the lip of the hole with my microphone on the edge and I waited as a desert gale blew over me and the sand caught in my hair and nose and ears and then, when the first artillery piece much later blasted a shell towards the Iranian lines, I switched on the recorder. I still have the cassette tape. The guns were dark against the sky as they bellowed away and I kept thinking of Wilfred Owen's description of the “long black arm . . . about to curse.” And there were twenty, thirty long black arms in front of me, more still behind the curtains of sand. And there, I recorded, unwittingly, my own future loss of hearing, 25 per cent of the hearing in my left ear which I would never recover. That very moment is recorded on the cassette:

We can see the gunnery officer just in front of us through this desert dust storm, feeding shells into the breeches of these big 155-mm Russian-made guns and preparing to cover their ears. The guns are so loud, they are leaving my ears singing afterwardsâBANGâThere's another one just gone off, a great tongue of fire about 20 feetâBANGâin front of itâBANGâ They're going off all around me at the moment, an incredible sight, this heavy artillery firing right in the middle of aâBANGâthere's another one, right in the middle of this dusty, windswept desert.

I can still hear that gun's distant echo in my ears as I write these words, a piercing tinnitus that can drive me crazy at night or when I'm tired or irritable or trying to listen to music or can't hear someone talking to me at dinner.

I turned on Iraqi radio. Further Iranian territory was about to “fall” and Iraqi generals were announcing a “last push” into Khorramshahr. Five days ago, the inhabitants of Basra were content to listen to news of the Iraqi advance on television, but now traders and shopkeepers in the city chose to supplement their knowledge by asking foreign journalists for information about the war. No one thought Iranian shells would still be falling on Iraqi soil this long after the invasion.

That evening, we were invited to tour Basra District Hospital, a bleak building of tiles and pale blue paint, a barrack-like edifice whose uniformity was relieved only by the neat flower-beds outside, the energetic doctors and, more recently, by the ubiquitous presence of Dr. Saadun Khalifa al-Tikriti, Iraq's deputy health minister. He was saluted and clapped on the back wherever he went, a short, friendly fellow with a mischievous smile and a large moustache. Everyone greeted Dr. al-Tikriti with exaggerated warmth, and when the minister made a joke, gales of laughter swept down the marble corridors. The Basra hospital had taken almost all the city's 500 wounded this past week but al-Tikriti had more than just his patients on his mind when he toured the wards. Foreign press correspondents were greeted with a short, sharp speech about the evils of civilian bombing, and the doctor stopped smiling and thumped his little fist on the table when he claimed that the Iranian air force deliberately killed Iraqi children.