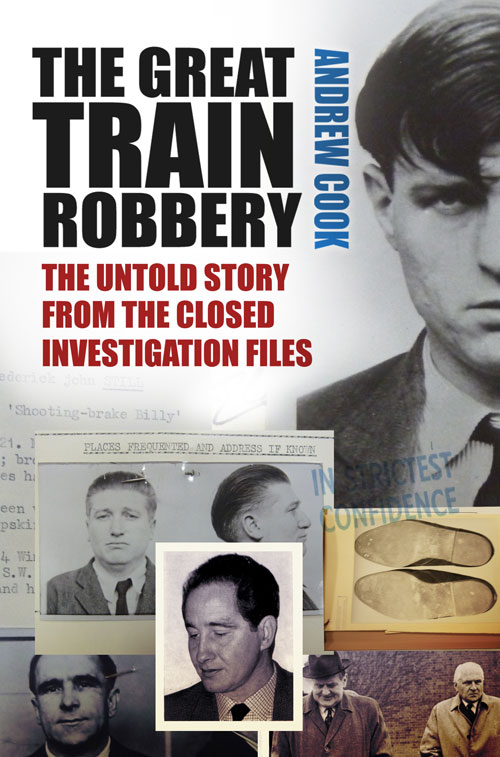

The Great Train Robbery

Read The Great Train Robbery Online

Authors: Andrew Cook

To Alia

I would like to thank all those involved in the research and development of this book, and the following people for their invaluable help:

Jordan Auslander, Bill Adams, David Baldry, Phil Tomaselli, Gavin McGuffie (BPMA), Jamie Ellal (BPMA), Sally Jennings (BPMA), Vicky Parkinson (BPMA), Helen Potter (TNA), Amelia Bayes (TNA), Lizzie Mould (Croydon Local Studies & Archives Service), Bob Askew (Southwark Council, Local History), Martin Robson Riley (National Museum of Wales), Andrew Foster (Railway History Group), Jen Parfitt (Solicitors Regulation Authority), David Capus (Records Management Branch, Metropolitan Police), Philip Barnes-Warden (The Met Historical Collection), Neil Paterson (The Met Historical Collection), Samantha Cardoo (Royal Mail Group Security), Tony Marsh (Group Security Director, Royal Mail Group), Janet Altham (DPP/CPS), John O’Connor (former Head, Flying Squad), Bob Fenton (EMCA), Philip Trendall (BTP), Edward Laxton (formerly of the

Daily Express

), Ray Brown (formerly of Lessor & Co.), Frank Campion (formerly of Lessor & Co.), Harry Lyons (former Assistant Controller, Post Officer IB), Bob Robertson (former Flying Squad), Edward Harris (former Flying Squad), Marlena Wilson (granddaughter of Percy Hoskins), Hazel Collinson (wife of Peter Collinson), Colin Williams (son of Frank Williams), Marian Ikin (daughter of Clifford Osmond), Roger Lemon, James Carpenter and Colin McKenzie.

Furthermore, I would like to thank Bill Locke at Lion Television (Executive Producer of the Channel 4 film

The Great Train Robbery’s Missing Mastermind?

), whose support and encouragement enabled me to take this project forward. I am also indebted to all those who were involved in the production of the film, in particular Matthew Whiteman, Luke Martin and Daisy Robertson.

Finally, my thanks to Chris Williamson, Beryl Rook, Alia Cook, Alison Clark, Nabeel Bashir, Simon Hamlet (who commissioned this book) and Lindsey Smith at The History Press.

2.

The Hold-Up

5.

The Poppy

11.

Fish on a Hook

Appendix 1

Jack Mills

Appendix 2

The Vehicles

Appendix 3

The Court

Appendix 4

Forensic Evidence on Gordon Goody’s Shoes

Appendix 5

Metropolitan Police Structure 1963

Appendix 6

Roy James’s Motor Racing Record

Just after 3 a.m. on Thursday 8 August 1963, a crime took place that still stands as the heist of the century. A gang of professional thieves made history when they held up the Glasgow to London Travelling Post Office train and seized a record-breaking haul of £2.6 million (just over £50 million in today’s money).

Much has been written about it over the past five decades in books, magazines and newspapers. A host of films and television documentaries have also ensured that not one year has passed since 1963 without coverage of the story and the characters involved.

However, despite the wealth and extent of coverage, a host of questions have remained unanswered about the Great Train Robbery: who was behind it, was it an inside job and who got away with the crime of the century? Fifty years of selective falsehood and fantasy, both deliberate and unintentional, has obscured the reality of the story behind the robbery. The fact that a good many files on the investigation and prosecution of those involved, and alleged to have been involved, are closed in many cases until 2045 has only served to muddy the waters still further. To piece together an accurate picture of the crime and those surrounding it, it is necessary to return to square one, starting from scratch in gathering together as many primary sources as possible. The ability to draw upon many formally closed, restricted or hitherto unpublished primary sources have helped in this task immeasurably.

Contemporary, primary source material undoubtedly gives the reader a totally new ‘feel’ for the case and the social attitudes of the period. The sheer volume of material also brings home just how easy it can be, without the ability to cross-reference other sources and investigations, to overlook certain details and key links. Many theories about the crime were expounded at the time, particularly in the popular press. Some of them were far-fetched; others were rooted in more reliable, off-the-record sources.

Files on the robbery held by the Metropolitan Police, the Home Office, Buckinghamshire Assizes, the British Railways Board and the Director of Public Prosecutions are vast and impossible to quote in full, as are the files held by Royal Mail, the British Transport Police and the contemporary newspaper reports held by the British Library. Therefore, a degree of selectivity has been applied, but not in such a manner as to compromise the integrity of the source material available. All the main official accounts and reports pertinent to the parallel investigations carried out by the various agencies are included in this book.

The objective of this book is to present as full and factual an account of the Great Train Robbery as is possible, chronologically presented and told by the people who played a role in the story. It is left to the reader to interpret the facts and evidence accordingly. Due to the great extent of abbreviations and initials used in the various documents, the reader is advised to periodically refer to the ‘Abbreviations used in Source Notes’ at the end of this book.

The term ‘The Great Train Robbery’ was neither born as a result of the 1963 mail train hold-up, nor indeed the 1855 train robbery immortalised by Michael Crichton in his 1975 novel

The Great Train Robbery

(which was later filmed by MGM in 1978 as

The First Great Train Robbery

starring Sean Connery and Donald Sutherland).

While Crichton’s book was a work of fiction, it drew heavily upon real-life events that took place on the night of 15 May 1855 when the London Bridge to Paris mail train was robbed of 200lb of gold bars. Crichton took something of a historical liberty by retrospectively re-christening it the Great Train Robbery. At the time, and for over a century afterwards, it was commonly known as the ‘Great Gold Robbery’.

The term ‘The Great Train Robbery’ has, in fact, no basis at all in any real-life event; it is instead the title of a 1903 American western movie written, produced and directed by Edwin S. Porter. Lasting only twelve minutes, it is still regarded by film historians as a milestone in movie-making. Shot not in Hollywood but in Milltown, New Jersey, its groundbreaking features include cross-cutting, double exposure composite editing and camera movement.

When, within twenty-four hours of the 1963 mail train robbery, the enormity of the heist began to sink in and the British press frantically searched for a suitable iconic headline, Edwin Porter’s 60-year-old movie title fitted the bill perfectly. Ironically, Fleet Street went one stage further the following week when, on the discovery of Leatherslade Farm, they dubbed it ‘Robbers’ Roost’. This secluded location in southern Utah was, in fact, a favourite hideout of the American outlaw and train robber Butch Cassidy and his ‘Hole in the Wall Gang’ back in the 1890s.

Mail was first carried in Britain by train in November 1830, following an agreement between the General Post Office and the Liverpool & Manchester Railway. Eight years later, Parliament passed the Railways (Conveyance of Mails) Act, which required railway companies to carry mail as and when demanded by the postmaster general. Trains carrying mail eventually became known as TPOs (Travelling Post Offices). Mail was sorted on a moving train for the first time in January 1838 in a converted horsebox on the Grand Junction Railway. The first special postal train was operated by the Great Western Railway on the Paddington to Bristol route, making its inaugural journey on 1 February 1855.

Because of the wide expanse of territory in the American West and Mid-West, train robbers tended to stop trains by placing obstructions on the track to halt the locomotive, or by boarding the train, jumping into the back of the locomotive and holding up the engineer and fireman.

The location chosen was usually a desolate or isolated stretch of line, miles away from the nearest town, where plenty of time would be available to rob the train and make a getaway well before the alarm was raised. Unlike the 1855 ‘Great Gold Robbery’ in England, there was no need to rob the train while it was in motion. Train robberies carried out by the likes of Jesse James and Butch Cassidy would have been impractical, if not near impossible, in Victorian England due to the short distance between stations and the observant signal box system.

By the time Butch Cassidy and his Wild Bunch hit the Union Pacific train at Tipton on 29 August 1900, the writing was already on the wall for American train robbers. The Board of the Union Pacific Railroad Company had resolved to spend money to save money - by employing the Pinkerton Detective Agency. Their agents, such as the legendary Joe Lefors, were usually well paid, well armed and mandated to take the fight directly to the train robbers. This they did by tracking them, sometimes for months on end, until they were arrested or forced into a gunfight. Unlike US law officers, Pinkertons were not constrained by state boundaries, which escaping robbers had previously exploited by criss-crossing. Pinkertons’ strategy, although criticised in many quarters as a shoot-to-kill policy, was to prove particularly effective in combating railroad robberies.

Unlike America, the regional railway companies in Britain (GWR, LMS, LNER and SR) were permitted by Parliament to employ their own railway police constabularies. With the nationalisation of the railways in 1948 and the creation of one sole state-owned company, British Railways, these private-company police forces became one constabulary known as the British Transport Commission Police. In Britain there was no need to employ the likes of Pinkertons to investigate mail crime, as a highly effective official force had operated in the shadows for over 300 years.

The Post Office Investigation Branch (IB) has a just claim to be the world’s oldest criminal investigation department, tracing its origins back to 1683, when King Charles II appointed Attorney Richard Swift to the General Post Office (GPO) with specific responsibility for ‘the detection and carrying on of all prosecutions against persons for robbing the mails and other fraudulent practices’. On a salary of £200 per year Swift was, according to GPO records, an effective bulwark against post office crime. A Treasury department letter of 1713 affirms that, ‘Richard Swift has been Solicitor to the General Post Office for about thirty years in which he has all along acted with great diligence, faithfulness and success.’

1

During the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, reports of the apprehension and sentencing of post office offenders appeared regularly in local and national newspapers. The

Evening Mail

of 8 May 1795, for example, reported in some detail on the case of a letter sorter by the name of Evan Morgan, who had been arrested and charged with ‘secreting a letter at the Post Office’. He was hung on 20 May at Newgate Prison. Of particular note was the fact that three of the six men hung that day were postmen.