The Great Fossil Enigma (19 page)

Read The Great Fossil Enigma Online

Authors: Simon J. Knell

Opposition began to mount in some quarters before Sylvester-Bradley and Moore commenced their consultations. Most vocal was the American Society of Parasitologists. This particular problem arose because Sylvester-Bradley and Moore had discussed their plans with parasite worker J. Chester Bradley and then extended the concept of parataxa to admit the unidentified life stages of these animals. Perhaps the two men felt the support of medical scientists might win the day. Now these scientists were complaining as a system of parataxa would require rather more formality than they desired. The commission asked Moore to consult these parasite specialists, which he did in New York, but he thought the whole thing an unwelcome and unnecessary distraction. This was, however, one parasite the parataxa scheme could not shake off. It produced the first major blemish.

The

ICZN

sent out a succinct version of the parataxa plan to paleontologists and paleontological institutions in July 1957. Soon letters of support were flooding into the editor of the

Bulletin

from all areas of the paleontological community, but it was not all good news. Some saw it as a recipe for chaos, while others were clearly annoyed to see Moore championing this particular cause. While Moore could attract the world's best paleontologists to write for the

Treatise

, and could certainly write a courteous response if required to do so, he was also known for his outspokenness and had created powerful enemies. Ray Bassler was not one of these, although he and Moore were often at loggerheads. And in this new proposal Bassler saw Moore making a second attempt to have his sea lily fragments scheme accepted. Bassler was perceptive; Moore certainly did have these in mind. Bassler saw this as a subversive assault on his position that, if successful, would have personal consequences for him and he complained, “Moore acknowledged that the fragments had no value as genera and species in classification. These fragments probably gave rise to the later term

PARATAXA.”

He dubbed Sylvester-Bradley “a European sponsor” and called for “all good naturalists to come to the aid of our taxonomy.” He felt that “common good sense” could deal with the problem: “Any name based upon an aptychus can remain until the whole shell is known, whereupon the aptychus-name can go in parenthesis labelled as the operculum. Conodonts can be treated likewise until the entire animal is found, maybe centuries later, but the old unlocated names must be held for stratigraphic reasons.” For the exasperated Bassler it simply wasn't worth wasting any further words on the subject.

Other objections came from groups in which similar problems had been dealt with using the existing rules. Only two conodont specialists objected. Both were at the Oklahoma Geological Survey. The first was Ted Branson's son, Carl, who was simply not convinced that natural assemblages were anything other than coprolitic: “Scott's assemblages are coprolitic associations. The validity of other assemblages is not demonstrated.” He added, “The names of 'assemblages', said to be natural genera, should be suppressed as unnecessary, premature, and hypothetical.” The second was Robert Fay, who used Branson's view to demonstrate how poorly conodonts were known: “At present there is no competent person to make a decision on the classification of conodonts” due to the unknowns. “We are proceeding along an odd pathâ¦. I vote that we dismiss this proposed insertion of parataxa into the

Règles

, because it is not sound, premature, and unnecessary, and highly subjective.” Conodont workers in support of the plan included Ellison, Schmidt, Furnish, Hass, and new boys Klaus Müller and Rhodes. But the conodont community was simply not large enough to swing the argument in its favor without help.

In some cases groups decided to respond en masse. In Washington, Bassler's call for revolt had hit home. The city's “Nomenclature Discussion Group” received votes from 56 of its 113 members, all against the plan. Bassler was, however, not recorded among the votes cast. These specialists came from a wide range of zoological and paleontological fields and each had considered the possible impact of parataxa on their field; all were certain that confusion would result. Given that the proposal made no suggestion that it should be adopted by all fields, Sylvester-Bradley thought this a peculiar turn of events. Hass, who was then the only conodont worker in Washington, had spoken in favor of the plan but had preferred to write directly to the commission. Hass's colleagues seemed to believe that the simple solution was to recognize no synonymy between the assemblage and the discrete element. In other words, do what Scott had done and ignore the problem.

Sylvester-Bradley responded to the Washington scientists publicly and somewhat defensively, explaining his relationship to Moore in the proposal â he had an interest in resolving taxonomic issues, and not as a specialist in the fossils used as cases for change: “My present interestâ¦is therefore, not that of the parent of a fond child, but still that of one of the Commissioners who is attempting to find a solution to a difficult nomenclatural problem.” Sylvester-Bradley no doubt understood some of the underlying issues that affected the Washington view. What Sylvester-Bradley wanted was constructive argument â not a vote. He encouraged the participants to contribute to the debate.

A meeting of the Institute of Zoology at the Polish Academy of Sciences also reached unanimity: The plan was rejected for use in zoology and accepted as a solution for a limited number of cases in paleontology. The meeting contained no paleontologists. Writing on behalf of the academy, Tadeusz Jaczewski sawparataxa as a kind of opiate that could lead to disfunction and laziness.

The British-based Palaeontological Association and Palaeonto-graphical Society also voted and came out strongly in favor of a system that served the peculiar needs of fossils like conodonts and stabilized their nomenclatures. But they were split down the middle on whether the parataxa proposals were the best solution. They were aware, for example, that entomologist Curtis Sabrosky at the U.S. Department of Agriculture in Washington had proposed an alternative plan based on the system used in paleobotany in which form taxa were well established. Although he disagreed with Sabrosky's definitions, Sylvester-Bradley thought this a possible solution. For him, the terms “parataxa” and “form taxa” were interchangeable. By some clever and subtle maneuvering of terms invented to describe parts of fossil plants, he used this moment to distance the problems of fossils from those of parasites. The latter, one might infer, were no longer part of the parataxa debate.

When Sylvester-Bradley came to summarize the results of the consultation, it was clear that the vote in Washington had sunk the scheme, at least in numerical terms. He had received fifty-three votes in favor of the plan, of which thirty-six had come from individuals. However, those against amounted to seventy-nine, fifty-six of which were votes from the Washington census. Only nine individuals had written in opposition. Sylvester-Bradley mulled over the imperfectly formulated alternatives that had also been put forward. The consultation overall lacked a firm conclusiveness. His published summary was followed by a single sentence letter from fossil fish specialist Errol White at the British Museum (Natural History): “I can answer your circular letter of the 8th July 1957, very briefly by saying that I am dead against special provision for Parataxa in the

Règles.”

The fate of the parataxa plan was decided at the Fifteenth International Congress on Zoology, which met at the British Museum (Natural History) in London in July 1958 to celebrate a centenary of Darwinian evolution. Just before the meeting, two letters arrived from the USSR, one from the Palaeontological Institute of the Academy of Sciences and the other from the Institute's Laboratory of Palaeoecology of Marine Faunas.

21

Both were translated from the Russian and revealed a remarkable conflict of view. The first letter, from the institute's president, Yuri Orlov, and secretary, Yanovsky, was succinct and fully in agreement with the parataxa plan. The second, from senior staff at the laboratory, which arrived a week later and had been drawn up independently, had not a single good word for Moore and Sylvester-Bradley's proposal. Their objections were considerable. They thought the plan had been proposed merely to preserve names â an act already possible under the rules â and not to extend knowledge. Indeed, they felt that the plan might actually circumvent scientific progress as workers could remain contented with the practicalities of an artificial system. Doubtless knowing precisely where American science had been heading, they said that even stratigraphers could not be excused the necessity of knowing their animals biologically. The argument gave strong indications of the chaos that might arise if two systems “separated, as by a wall” were permitted to exist. All paleontologists, they pointed out, deal with mere parts of animals.

The colloquium that preceded the meeting decided to defer the question, asking a committee, to which Moore was appointed, to report to the Washington Congress in 1963.

22

The conodont volume of the

Treatise

remained on hold a little longer, the outcome of the parataxa plan critical to its content.

On November 30, 1959, Hass died prematurely; Arkell had died the year before. Hass's loss was a tremendous blow to the

Treatise

project, so Moore brought in two young bloods who were already revolutionizing the conodont in terms of its understanding and significance: Frank Rhodes and Klaus Müller. Both men had published reviews of conodont knowledge, and although neither were Americans, both had first met in Iowa, where Müller was on sabbatical in 1955. They immediately hit it off and had prepared a joint paper.

23

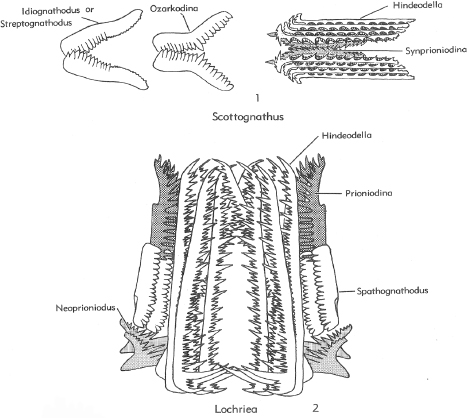

5.1.

Hass's compromise. Scott's and Rhodes's conodont assemblages as published by Hass in the

Treatise of Invertebrate Paleontology

in 1962. Hass had died before the idea of parataxa had been rejected, and his dual classification of conodonts retained, at very least, the ideal of parataxa. Here “biologic” genera (assemblages) are composed of “utilitarian” genera (conodont elements). From W. H. Hass,

Treatise of Invertebrate Paleontology

, Part W Miscellanea (1962). Courtesy of and ©1962, The Geological Society of America and The University of Kansas.

By mid-1961, Moore recognized that the parataxa plan was dead â it was certainly delaying publication of the

Treatise

â and that the committee would recommend to the

ICZN

that it should give it no further consideration. Moore had, following the London meeting, consulted Hass, Müller, and Rhodes but remained dissatisfied. Hass had already retained Scott's dual system in the

Treatise

separating a “utilitarian” taxonomy for individual elements from an uncertain “biologic” group using the names Scott and Rhodes had introduced (

figure 5.1

). In an unprecedented move â Moore usually left the content of the

Treatise

volumes to the specialists themselves â he published his own statement. The concept of form species, he said, could not be used, and Rhodes's construction of species of assemblage composed of species of element was “unhelpful.” He became an advocate for doing things according to the rules. His solution was to follow Sylvester-Bradley's observation and not to admit to an exact identity for the components making up an assemblage.

24

By that means all names might actually exist within a single system.

Rhodes, who had recently moved to the University of Wales in Swansea, felt Moore was entirely on the wrong tack. He told him that the fossils were not as ambiguous as Moore wished to pretend â one certainly could place discrete conodont fossils into assemblages. A fully paid-up supporter of the parataxa plan, Rhodes found Moore's plan more damaging than useful.

25

But Moore was emphatic, arguing that “dual nomenclature is not only unacceptable and illegal, but it is unnecessary.” He warned: “Let us agree, then, on adopting a conservative, unassailable course which takes us around or away from conflictâ¦. Bold workers who wish to proceed differently may do so, but then they are enjoined to tread carefully and follow through to ends that accord with the Rules.”