The Great Fire of Rome: The Fall of the Emperor Nero and His City

Read The Great Fire of Rome: The Fall of the Emperor Nero and His City Online

Authors: Stephen Dando-Collins

Tags: #History, #Ancient, #Rome

BOOK: The Great Fire of Rome: The Fall of the Emperor Nero and His City

3.02Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Table of Contents

Acknowledgments

My sincere thanks go to Bob Pigeon, executive editor with Da Capo Press, for commissioning this work. It turned out that Bob and I had shared a fascination with the Great Fire of Rome for many years.

I also extend grateful thanks to my New York literary agent, Richard Curtis, for putting Bob and me together.

And, as always, I record my gratitude to my wife, Louise. She has been the great fire in my life for the past twenty-eight years.

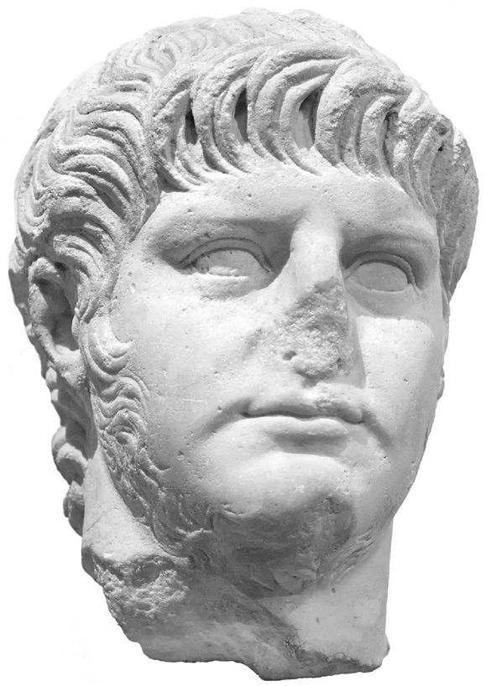

Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus, 37-68 AD (Antiquarium of the Palatine)

INTRODUCTION

R

ome’s Great Fire is one of the best known of all historical events. Yet, strangely, few books have been written about the fire and the events surrounding what came to be one of history’s great turning points—the end of the Roman dynasty created by Julius Caesar.

ome’s Great Fire is one of the best known of all historical events. Yet, strangely, few books have been written about the fire and the events surrounding what came to be one of history’s great turning points—the end of the Roman dynasty created by Julius Caesar.

Could it be that we think we know all there is to know about that great catastrophe? Who, after all, has not heard the story about the mad emperor Nero setting fire to Rome and then fiddling while the city burned around him, only for him to blame the Christians for the fire and to make human torches of them? Ah, but was Nero mad, did he set the fire, did he fiddle, and did he in fact burn a single Christian? Was there much more to the Great Fire than previously believed?

In the twentieth century, many scholars and historians began to reap-praise Nero the ruler. Has Nero been misrepresented down through the ages? Certainly, the fiddling incident can quickly be consigned to myth. The fiddle was an instrument that did not emerge in Europe until a millennium after Nero. So, Nero did not fiddle while Rome burned. Did he perhaps play some instrument? The lyre, for example? Yes, he was a noted player of the small, harplike lyre, the only stringed instrument used by Romans in classical times. But did he play the lyre at Rome on July 19, AD 64, or during the following days, while Rome burned?

If we are to believe Tacitus, one of Rome’s more reliable first-century historians, who lived through the Great Fire as a nine-year-old, Nero did not play the lyre at Rome while the city burned. But he did play the lyre on the night the fire broke out—Tacitus put Nero at the city of Antium, modern-day Anzio, on the west coast of Italy, playing the lyre. Not that this would preclude Nero from having ordered the lighting of the fire.

Nero, said Tacitus, played the lyre in a musical competition at Antium, the emperor’s birthplace, on the evening of July 19. After he was informed of the fire, he returned to the capital, where he industriously directed firefighting operations and the provision of shelter and food for the population. It was another Roman historian, Cassius Dio, a senator, onetime consul, general, and governor of several Roman provinces, who wrote that Nero gleefully played the lyre at Rome while the city burned, and it is primarily from him that the fiddling-while-Rome-burned story has come down to us. But Cassius Dio wrote his version of events some 165 years after the Great Fire. And in writing what he did about Nero and the fire, Dio evidently misinterpreted or misquoted Tacitus and another first-century Roman historian, Suetonius.

Here, in part, is what Dio said, in the third century, about the way the Great Fire of Rome started, laying the blame for the conflagration squarely at the feet of Nero: “He secretly sent out men who pretended to be drunk or engaged in other kinds of mischief, and caused them to first set fire to one or two or even several buildings in different parts of the city, so that the people were at their wits end, not being able to find any beginning of the trouble nor to put an end to it.”

1

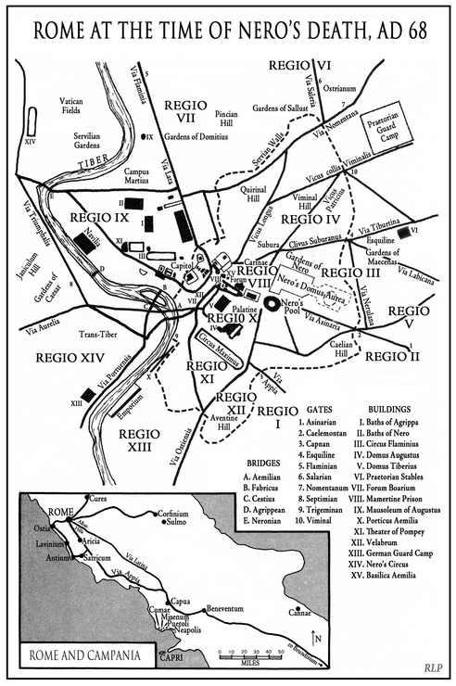

This claim by Dio, that the fire of AD 64 was deliberately set in a number of buildings in different parts of the city, is at variance with the information from Tacitus. The Tacitus version, which is widely accepted by historians, says that the Great Fire began at a single location, the Circus Maximus. But let us follow Dio’s line a little further.

1

This claim by Dio, that the fire of AD 64 was deliberately set in a number of buildings in different parts of the city, is at variance with the information from Tacitus. The Tacitus version, which is widely accepted by historians, says that the Great Fire began at a single location, the Circus Maximus. But let us follow Dio’s line a little further.

He also wrote, after graphically describing how the fire affected the city’s million or more residents and caused widespread grief: “While the whole population was in this state of mind, and many, crazed by the disaster, were leaping into the very flames, Nero went up to the roof of the Palatium [his palace on Rome’s Palatine Hill], from which there was the best general view of the greater part of the conflagration, and assuming the dress of a lyre-player, he sang the ‘Capture of Troy,’ as he called the song himself, though, to the eyes of the spectators, it was the Capture of Rome.”

2

2

To begin with, everything on the Palatine Hill, including the Palatium, was, as Dio himself would write, destroyed in the fire. Along with every other building on the Palatine Hill, the palace was consumed in the fire’s first stage. Even if we assume that Dio meant that Nero ascended the Palatium roof to play his lyre during the early stages of the fire, before the flames reached the palace, no other Roman writer put Nero on the roof of his palace at Rome, playing the lyre, at any time during the Great Fire. Tacitus wrote that Nero only set off back to Rome when he heard that the fire was approaching his palace.

Dio clearly took his lead from Nero’s biographer Suetonius, whose parents actually lived at Rome at the time of the Great Fire—Suetonius himself was born some five years later. Suetonius made Nero culpable for the conflagration, writing:

Pretending to be disgusted by the drab old buildings and narrow, winding streets of Rome, he [Nero] brazenly set fire to the city. Although a party of ex-consuls caught his attendants, armed with tow [the coarse and broken part of flax and hemp] and blazing torches, trespassing on their property, they dare not interfere.

Suetonius went on to say of Nero:

He also coveted the sites of several granaries, solidly built in stone, near the Golden House. Having knocked down their walls with siege engines, he set the interiors ablaze. The terror lasted for six days and seven nights, causing many people to take shelter in monuments and tombs. Nero’s men destroyed not only a vast number of apartment blocks, but mansions that had belonged to famous generals and were still decorated with their triumphal trophies. Temples, too, vowed and dedicated by (Rome’s) kings, and others during the Punic and Gallic wars. In fact, very ancient monuments of historical interest that had survived up to that time. Nero watched the conflagration from the Tower of Maecenas enraptured by what he called “the beauty of the flames,” then put on his tragedian’s costume and sang “The Sack of Ilium” from beginning to end.

3

Here then was Suetonius’ account, written several decades after the event, in which Nero was described as singing while Rome burned, but not from the roof of his palace. Cassius Dio wrote his history of Rome using the works of earlier writers, adding his own opinions, biases, and flourishes—such as changing the name of the tune supposedly played by Nero, apparently to give more emphasis to the claim that Nero celebrated the destruction of his capital. And, of course, Suetonius’ account of the fire was one to which Dio would have had access long after it was written.

Even though Tacitus makes no mention of it, there is a high probability that when Nero arrived back at Rome from Antium, he did indeed observe the fire from the vantage point of the Tower of Maecenas, which stood on the Esquiline Hill, in the imperial gardens of Maecenas—the fire was eventually brought to a halt at the foot of the Esquiline. And perhaps Nero did sing a song or two during that fraught week of the fire. But did he celebrate the fire, and did he in fact set it, as Suetonius, alone among first- or second-century writers, claimed and as Dio much later echoed?

Other books

Freed by Tara Crescent

The Fourth Man by K.O. Dahl

Her Smoke Rose Up Forever (S.F. MASTERWORKS) by James Tiptree Jr.

Let's Get Invisible by R. L. Stine

FAMILY FALLACIES (The Kate Huntington mystery series #3) by Kassandra Lamb

Julius Caesar by Ernle Bradford

Cruel Comfort (Evan Buckley Thrillers Book 1) by James Harper

At Wick's End (Book 1 in the Candlemaking Mysteries) by Tim Myers

Live and Let Shop by Michael P Spradlin

Punished by Passion by Nottingham, Cara