The Gospel According to Larry (2 page)

Read The Gospel According to Larry Online

Authors: Janet Tashjian

Joining anything was not my usual thingâby a long shot. It's like that show

Survivor.

I read in the paper that 50 million people watched it last nightâtalk about a reason

not

to watch something. I don't know about you, but if 50 million people are doing something, I want to be doing something elseâ

big

time.

Survivor.

I read in the paper that 50 million people watched it last nightâtalk about a reason

not

to watch something. I don't know about you, but if 50 million people are doing something, I want to be doing something elseâ

big

time.

My stepfather's girlfriend calls me quirky, but most of the kids in my school would probably just call me weird. I'm used to it, though; it's always been that way. I mean, when you're sitting in third grade wearing a paper pyramid on your head to see if the rays of energy will help you concentrate, you're getting some kids looking at you like you're cuckoo. The good news wasâI never cared. Never came home crying, never worried, “Oh, gosh, what will the other kids think?” Just plain old

oblivious. There's something to be said about ignorance being bliss.

5

oblivious. There's something to be said about ignorance being bliss.

5

When my mother was still alive, she used to threaten the principal for more servicesâextra tutors, more challenging work. “He's seven years old with an eighth-grade math level. You're wasting his time making him add two plus two!” she'd yell. “I'll homeschool him, I swear!”

Yeah, Mom. Sure. Maybe after a handful of Prozac and a lobotomy. God rest her soul, she was a tireless advocate for me, but she could sit still about as much as I could. I can picture her homeschooling me now, the two of us spelling vocabulary words as we rolled down the hill behind the cemetery. She was a characterâloud voice, loud music, loud clothes. So much fun. Until the ovarian cancerâmuch less fun after that.

For most of my life with her, the stimulation level was high, and that's always been a turn-on for me. I didn't crawl or walk; one day I just got up and ran. My very first wordâyelled, not spoken from my carseat as we cruised down the highwayâwas

FASTER!

And once

I got hold of numbers, forget about it. There's a home video of me, probably about two years old, sitting on one of those jumpy seats in the kitchen. I'm in front of the refrigerator with colored magnetic numbers doing equations.

6

My mother's talking to one of her girlfriends while she's taping me, saying, “When most babies want formula, they're not talking about math.”

FASTER!

And once

I got hold of numbers, forget about it. There's a home video of me, probably about two years old, sitting on one of those jumpy seats in the kitchen. I'm in front of the refrigerator with colored magnetic numbers doing equations.

6

My mother's talking to one of her girlfriends while she's taping me, saying, “When most babies want formula, they're not talking about math.”

But it wasn't just numbers; it was learning in general that excited me. I'd go through phases where I devoured any information about the Civil War, Tibetan Buddhism, alpine mountaineering, and planting a perennial garden.

7

The usual kid activities like baseball and soccer didn't interest me. I remember having huge fights with my mother while she held open the screen door and forced me to play outside with the neighborhood kids. “If you don't go out and play with Karl and Bryan right now, there'll be no science homework after dinner!”

7

The usual kid activities like baseball and soccer didn't interest me. I remember having huge fights with my mother while she held open the screen door and forced me to play outside with the neighborhood kids. “If you don't go out and play with Karl and Bryan right now, there'll be no science homework after dinner!”

“Don't even think about taking my biology away!”

“Josh, get out there and get some fresh air, or so help me God, I'm bringing those math books back to the library!”

She'd boot me out the door kicking and screaming. As the years went by, I still preferred to work on my laptop in my hammock swing than to be at the high school Super Bowl.

Beth used to call me “The Wizard,” like I was some overgrown Harry Potter. She thought I just twirled around, wasting time, visiting various dictionary sites to look up words like

napiform

(it means turnip-shaped, but you know that).

napiform

(it means turnip-shaped, but you know that).

“You are NOT the average seventeen-year-old,” she told me once. “But then again, you weren't the average fifteen- or twelve-year-old either.”

I had to agree with her there.

It's very simple, really. I've only wanted one thing my whole lifeâto contribute, to help make the world a better place. It sounds amazingly corny, but pushing civilization forward has always been my highest priority. Not with more technology, not with more money, but with more ideas, more meaning. When we studied Darwin last year, his ideas burned off the page. All of us, evolving, moving forward, consciously or not. It's probably what was in

the back of my mind when I moved those plastic numbers across the refrigerator; it's what's on my mind as I type this now.

the back of my mind when I moved those plastic numbers across the refrigerator; it's what's on my mind as I type this now.

If Larry was a way to delve into life's deeper meaning, then count me in.

Beth made a list of all the kids in our homeroom and who they had been in a past life. We passed the list back and forth filling in the blanksâJack Furtado, Victorian cellist; Laura Newman, Russian cosmonautâuntil the bell rang.

Out in the hall, my enthusiasm pinned Beth to her locker. “You're right! Everything Larry wrote about on his Web site had something to do with my life.”

“Didn't I tell you?” She couldn't have been happier.

“When I thought about what a consumer glutton my stepfather's girlfriend was, Larry wrote about shopaholics. When I missed my mother, he talked about attachment. It was uncanny!” I didn't want to lay it on too thick.

Beth's lips shone like a hot mocha coffee. “He puts into words exactly what we're thinking.” She corrected herself immediately. “He

or

she.”

or

she.”

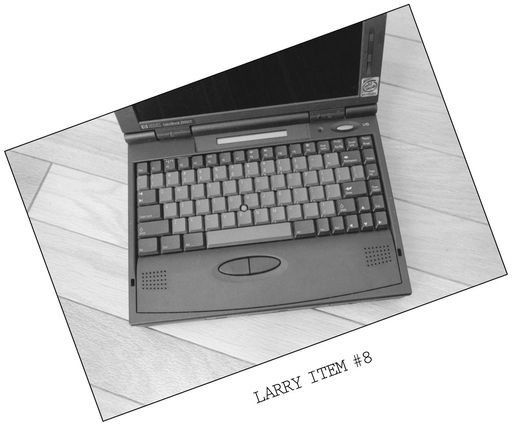

“But what's with the photos?” I asked. “Are we supposed to guess Larry's identity?”

“Larry has less than eighty possessions. He posts them on his Web site, a few at a time, daring people to guess who he is. Right now, everyone's clueless. I mean, what can you tell from a pen and a hairbrush?”

“Maybe you'll be lucky and the next clue will be hisâ”

“Or herâ”

“License.”

Beth smiled. “I'm sure Larry's saving that one for last.”

I asked her if she wanted to come over later and talk about my ideas for the club.

She frowned. “I can't. I have to study for that calculus test.”

Beth was a lot of thingsâgorgeous, smart, determined. She also was a terrible liar. I stared her down.

“Okay, I promised I'd help my father with inventory.”

I kept staring.

“Damn it, Josh. I told Todd I'd help him clean his basement tonight. Okay?”

“Could you please explain how someone as committed to personal growth as you are can

vacuum the basement of the class cretin just because she thinks she's in love with him?”

vacuum the basement of the class cretin just because she thinks she's in love with him?”

“I don't want to hear it,” Beth barked back. “There's no one more inconsistent than you. You're a computer geek who hikes in the woods for days. You hate to buy things, yet you always go to Bloomingdale's!”

“That's different. But forget it, you made your point.”

She was just gearing up. “Look, you're my best friend. We've been bailing each other out since grade school. But not everyone wants to go through life being a hermit living in the world of ideas.” She made quotation marks with her fingers when she said the word

ideas.

It was one of the only things Beth did that drove me out of my mind.

ideas.

It was one of the only things Beth did that drove me out of my mind.

She finally got around to sputtering out the truth about Todd. “He's the only cool guy who's ever liked me. I know he can act like a jerk, but do you mind if I let his popularity rub off on me for a while?”

For some reason the bare-bones honesty of her plea only fueled my growing sense of annoyance. “I'm out of here.” I made those fake quotation marks around the word

out,

then walked

toward lit class. I could feel her behind me even before she spun me around to face her.

out,

then walked

toward lit class. I could feel her behind me even before she spun me around to face her.

“I hate fighting with you,” she said. “Hate it, hate it, hate it.”

We stood silently for a few minutes.

“It's just that Todd has to have the basement cleaned by the weekend or he can't play. I'm trying to have some school spirit for once. Plus, he knows I'm really good at organizing things ⦠.”

I wanted to tell her those skills might be put to better use than placing football and basketball trophies in chronological order, but I held my tongue. Instead I told her I had lots to do, tons to do, was way too busy to deal with this paltry exchange. I shuffled away as nonchalantly as someone in deep despair could shuffle. My anxiety around Beth could be traced to one thingâI was never included in the endlessly rotating list of guys she had crushes on. Sam, Daniel, Andy, Speedy McDermott, Jack, now Todd. But never, ever me. If the choice were a two-week exciting vacation in Europe with me or helping Todd clean his basement, I knew, sadly, what Beth's choice would be.

Next stop in my fun-filled day: guidance with Ms. Phillips. I tried to rally myself for

the occasion by doing some standing push-ups against my locker.

the occasion by doing some standing push-ups against my locker.

I hadn't even sat down when Ms. Phillips got to the point. “Have you thought about your major, Josh?”

Ms. Phillips had the terrible habit of pushing her glasses up her nose with her middle finger. She did it so often, everyone in school called her Flip-Off Phillips.

I played with the zipper of my bookbag, then realized I was not giving her my full attentionâLarry's Sermon

#

22. I looked her in the eyes. “I was thinking about philosophy. You know, the meaning of lifeâthat sort of thing.”

#

22. I looked her in the eyes. “I was thinking about philosophy. You know, the meaning of lifeâthat sort of thing.”

“From the point of view of someone who likes to read, likes to think, like you do, it's a good choice,” she said. “But you realize the job prospects are pretty slim.”

“I'm thinking after the Depression, after the Apocalypse, there'll be lots of positions for people with depth and vision.”

She crinkled up her nose, her glasses fell, and she flipped me the bird again. “Josh, I'm not sure it makes sense to plan a career based on an apocalypse. What if there isn't one?”

“Then I guess I'm screwed.” I flashed her a big smile so she couldn't yell at me for the language.

“I suppose I'm being too materialistic,” she said. “Studying philosophy at Princeton is a fine and worthy choice.”

I wasn't sure Ms. Phillips's revelation came less from my sales pitch than it did from the fact that it was ten to eleven and she was dying for a cigarette before her next appointment. I decided to let her off the nicotine hook; I gathered up my things and headed for the door.

I've had a soft spot in my heart for Ms. Phillips since last year, when I spotted her e-mail address in her office and started up a chatty Internet conversation with her as a forty-year-old bachelor from Portland.

8

After months of quiet online flirtation, I invited her to meet me at the Borders coffee shop, only to watch her from the cookbook section. She waited more than two hours and three cappuccinos before she went home. (

That

I felt bad about. Ms. Phillips was usually tough as nails; I never thought she'd fall that hard.)

8

After months of quiet online flirtation, I invited her to meet me at the Borders coffee shop, only to watch her from the cookbook section. She waited more than two hours and three cappuccinos before she went home. (

That

I felt bad about. Ms. Phillips was usually tough as nails; I never thought she'd fall that hard.)

I decided to skip the rest of the day; the recurring vision of Beth dressed up like Snow

White singing as she swept Todd Terrific's basement was more than I could endure. I grabbed my camera from my locker and opted to check in with my mother instead.

White singing as she swept Todd Terrific's basement was more than I could endure. I grabbed my camera from my locker and opted to check in with my mother instead.

When my stepfather visited Mom, he headed for the cemetery. Iâwho knew her much better than he didâheaded for somewhere that captured her spirit more than a pasture full of granite headstones.

The makeup counter at Bloomingdale's.

I slogged through the slush, then grabbed the bus to Chestnut Hill. Ever since we lived in the Boston area, my mother had dragged me here once a month.

The waft of perfumes hit me like a surge of memories. I plopped down in the tall seat at the Chanel counter. I think it's safe to say I was the only person in that department sitting in the lotus position.

“Hello, Joshie. How's it going?” Marlene the Beauty Doctor has been working here for more than twenty years. With her shiny helmet of dyed black hair and dark eyebrows penciled in for the ones she lost years ago, she was Mom's favorite salesperson.

“It's slow, so you can sit. If I get a client, you know the drill.”

I saluted, then leaned back to hang with Mom.

My mother bailed on her wealthy parents' expectations as soon as she hit college. Instead of following in their Wall Street footsteps, she hitchhiked cross-country, worked tirelessly for civil rights, and made some bad choices in men. One thing from her Grosse Pointe background she couldn't walk away from, however, was her fondness for upscale moisturizers and creams. She used to spend hours trying to look like she wore no makeup at all. She experimented with pencils and powders like a mad scientist but always looked the same to me. I can remember perching on this stool as a preschooler watching Marlene hand Mom tube after tube of lipstick. Mom would ask me which color I preferred, consider my answer, then buy whichever one she wanted anyway.

My mother bailed on her wealthy parents' expectations as soon as she hit college. Instead of following in their Wall Street footsteps, she hitchhiked cross-country, worked tirelessly for civil rights, and made some bad choices in men. One thing from her Grosse Pointe background she couldn't walk away from, however, was her fondness for upscale moisturizers and creams. She used to spend hours trying to look like she wore no makeup at all. She experimented with pencils and powders like a mad scientist but always looked the same to me. I can remember perching on this stool as a preschooler watching Marlene hand Mom tube after tube of lipstick. Mom would ask me which color I preferred, consider my answer, then buy whichever one she wanted anyway.

I waited till Marlene rang someone up at the other end of the counter before I started talking.

“Okay, Mom, in a nutshellâBeth is cleaning Todd's basement, Peter is dragging me to another lasagna dinner at Katherine's, and I'm nowhere closer to changing the world.”

A woman with a leopard-print hat eyed me as she walked by.

“I just feel like I'm waiting for my life to begin, that I've wasted seventeen years. Then

what? Four years at Princeton? How does that help move civilization forward?”

what? Four years at Princeton? How does that help move civilization forward?”

“You want to see our deep-pore cleaning mask?” Marlene inquired.

I nodded. Whenever Marlene's boss circled by, I pretended I was a paying customer.

“You ask me, you make it too hard on yourself. Stop worrying about civilization. Worry about staying out of trouble, making nice friends,” Marlene said.

She rubbed the mask onto my face in small circles.

“I have nice friends,” I answered. “Well, one nice friend.”

“One nice friend is all you need.” Marlene watched her boss get on the escalator, then wiped off my mask with a tissue.

“Here.” She gathered up tiny bottles of free samples, put them in a small bag with handles, and gave it to me. “You come back anytime.”

I could see Marlene eyeing a potential customer hovering over the nail polish. I saluted again and left.

In the shoe department, I tried on four pairs of sneakers, three pairs of loafers, and five pairs of boots before the salesperson deserted me. I circled by the makeup counter on my way out.

“Mom?” I asked.

A fiftyish woman in fishnets turned around, then went back to what she was doing.

“Mom, you'll help me, right? With the whole change-the-world thing?”

Then I did what I always did when I needed an answer from my mother. I listened for the very next word someone said. A businessman talking on his cell phone provided her response.

“Yes!” he said into the phone. “Of course I will.”

My grin spread ear to ear.

When I said, “Thanks, Mom,” the woman in fishnets turned around again. I tipped my woolen hat her way and headed out of the store.

Other books

Anne Gracie - [The Devil Riders 02] by His Captive Lady

The Opposite of Everyone: A Novel by Joshilyn Jackson

The Wheelwright's Apprentice by Burnett, James

Never Seduce A Scoundrel by Grothaus, Heather

Winter (Rise of the Pride, Book 2) by Theresa Hissong

Frontier Inferno by Kate Richards

Elphame's Choice by P.C. Cast

Legal Heat by Sarah Castille

The Shattered Mountain by Rae Carson

Whiskey Kisses by Addison Moore