The Good Soldiers (36 page)

Authors: David Finkel

Tags: #History, #Military, #Iraq War (2003-2011)

“Little Miller was putting a can of gas in the trunk. The National guy gave him a date,” he said, and he didn’t bother with the rest of it: that the reason the Iraqi gave him a date was out of gratitude; and the reason for the gratitude was that the Americans had come to save him; and the reason that the Americans had come to save him was because they had been trying to save him since 2003, when the number of dead American soldiers was zero and Patrick Miller was nineteen years old and about to start college and thinking that he was going to become a doctor. And instead:

“He took a date and ate it and gave the guy the thumbs-up and got back in the truck,” Showman said, and then the truck took off on a route that Showman had just thought of, which led straight into an exploding EFP.

“We had two options,” he explained to Kauzlarich, “either go back the exact same way we came, or try to get down Florida.” He recounted a conversation he’d had with a soldier named Patrick Hanley, who was the truck commander in the lead vehicle and would typically be the one to choose the route.

“Hey, dude, we’ve got these two options,” he’d said. “I’d like to try it on Florida because I don’t think they’ll be expecting it.”

“All right,” replied Hanley, who was about to give his entire left arm to the cause of freedom, as well as part of the left temporal lobe of his brain, which would leave him unconscious and nearly dead for five weeks, and with long-term memory loss, and dizziness so severe that for the next eight months he would throw up whenever he moved his head, and weight loss that would take him from 203 pounds down to 128. “Let’s do it.”

And so they did it.

Truck number one: Hanley was right front. A soldier named Robert Winegar, who was about to be broken open by shrapnel in his arm and his back, was driving. A soldier named Carl Reiher, who was about to lose one of his hands, was right rear. Bennett, up in the turret, was gunner. Miller, the taste of a date still fresh on his tongue, was left rear.

Truck number two: Showman was right front, watching truck number one through his windshield as it squeezed between some barriers and rolled over what seemed to be an old, rusted piece of a gate.

“Got through fine,” Showman said to Kauzlarich.

Now Showman’s Humvee rolled over the gate and lost a tire. “We were still rolling fine on the flat. I thought, ‘We’re a click and a half out. Fuck it.’ Kept on rolling.”

Now truck number one, moving along Route Florida, saw something suspicious and swerved.

“He took a real wide berth around it. All of the trucks did. Swung off the road, actually; went around and back on the road.”

Got through fine.

Kept on rolling.

“Twenty meters up the road, right at the intersection, there’s a little mud hut right there, off to the left, and then there’s a light pole. They set it right in front of the light pole,” he continued. “They must have camouflaged it real good because—”

“It’s where those fuckers sell gas all the time?” Kauzlarich interrupted. “That mud hut?”

“Roger,” Showman said.

“So it was on the ground, you think?”

“Roger,” he repeated, and then stopped talking. Maybe he was seeing what was next.

“You guys did the battle drill,” Kauzlarich said after a bit, trying to help him.

“I mean, I probably don’t remember thirty seconds of this,” Showman said. His voice had been getting quieter and quieter. Now he could barely be heard. “I was right on Hanley’s ass. The next thing that I really do remember is the radio being in my hands, and I was hollering, ‘Outlaw Six, we got hit at the intersection of Florida and Fedaliyah,’ and then I told Mannix”—his driver—“to stomp the gas and haul ass. I couldn’t see the truck at the time. The road ahead of me was clear back to the COP. We shot through the kill zone and then we got up just a little ways, probably thirty meters. The truck had rolled off the road to the left. There’s like a garden and courtyard, and there’s nothing past it, just a big dirt yard. The truck had pulled behind that courtyard. I told Mannix to pull up right alongside. We started taking heavy small-arms fire. I told Mannix to pull up. There was a house and the truck, and then just everything else.”

Everything else:

“He was just white, with blood running down the side of his head, his eyes were vacant.”

That was Winegar.

“I thought he was dead. Dead weight. Just completely unresponsive. Eyes were wide open. I grabbed his ass to boost him into the truck, and my hand just slipped away. It was covered with blood.”

That was Reiher.

“And then Hanley?” Kauzlarich asked.

“Yeah. You could tell right away that it was severe head trauma because of the way his eyes were rolled back in his head, and he was foaming at the mouth,” Showman said.

And Bennett?

And Miller?

“I told Outlaw Six we needed a medevac at COP Cajimat,” Showman said of what he did next. He started to say something else, to explain why he hadn’t directed the convoy to the FOB, where a medevac would have had an easier time landing, but his voice trailed off. “Because it was close,” he said, and his voice trailed off again.

“It was the right call. It was the right call, Nate,” Kauzlarich said. “And then the route you took—you had two choices.You picked the least of two evils, given the Ranger rule of never going out the same way you came in.”

Showman looked at him, said nothing.

“It’s fucked up. But you did the right thing,” Kauzlarich said.

“The boys were still inside,” Showman said.

“There’s nothing you could do for them,” Kauzlarich said.

“Yes, sir,” Showman said, and that could have been the end of the conversation, confession made, forgiveness received, but for whatever reason, he needed to say it out loud.

“It took Little Miller’s head right off,” he said. “It went right through Bennett. When I opened that back door where those two were sit-ting . . .

“They didn’t know what hit them,” Kauzlarich said.

But that wasn’t the point. The point was that they had been hit.

Showman was looking at the floor now. Not at Kauzlarich. Not at the box of dust-covered soccer balls waiting to be given out. Not at the wall map of Iraq fucking itself. Just the floor.

The point was that he had thought of the route.

“So,” he said, sighing.

Four hundred and twenty days before, when they were all about to leave for Iraq, a friend of Kauzlarich’s had predicted what was going to happen. “You’re going to see a good man disintegrate before your eyes,” he’d said.

Four hundred and twenty days later, the only question left was how many of the eight hundred good men it was going to be.

On one end of the FOB, the soldier who had spent hours stacking sandbags until the entrance to his room was a tunnel pronounced himself ready for the next rocket attack.

In another part of the FOB, soldiers were learning that one of the rounds they had fired after being hit by two IEDs on their way to get Showman’s platoon had gone through a window and into the head of an Iraqi girl, killing her as she and her family tried to hide.

In another part, a soldier was thinking about whatever a soldier thinks about after seeing a dog licking up a puddle of blood that was Winegar’s, or Reiher’s, or Hanley’s, or Bennett’s, or Miller’s, and shooting the dog until it was dead.

The good soldiers.

They really were.

“The war’s over for you, my friend,” Kauzlarich said now to Showman, and of all the things he had ever said, nothing had ever seemed less true.

13

APRIL 10, 2008

I want to say a word to our troops and civilians in Iraq. You’ve performed with

incredible skill under demanding circumstances. The turnaround you have made

possible in Iraq is a brilliant achievement in American history. And while this

war is difficult, it is not endless. And we expect that as conditions on the ground

continue to improve, they will permit us to continue the policy of return on success.

The day will come when Iraq is a capable partner of the United States. The day will

come when Iraq is a stable democracy that helps fight our common enemies and promote

our common interests in the Middle East. And when that day arrives, you’ll come home

with pride in your success and the gratitude of your whole nation. God bless you.

—

GEORGE W. BUSH

,

April 10, 2008

Y

ou know what I love? Baby carrots. Baby carrots and Ranch dressing,” a soldier said. “I think I’m going to be eating some baby carrots when I get home.”

“Shhh,” another soldier said, eyes shut. “I’m on a pontoon boat right now.”

They were done. They were all done. It was April 4. In a few hours, once it was dark, some Chinook helicopters would cut across the night shadows toward Rustamiyah. Soon after that, the first 235 of them would be on their way out, and by April 10, all of them would be gone.

Rustamiyah to the Baghdad airport.

Baghdad to Kuwait.

Kuwait to Budapest.

Budapest to Shannon, Ireland.

Shannon to Goose Bay, Canada.

Mortuary Affairs

Goose Bay to Rockford, Illinois.

Rockford to Topeka, Kansas.

Topeka to Fort Riley, by bus.

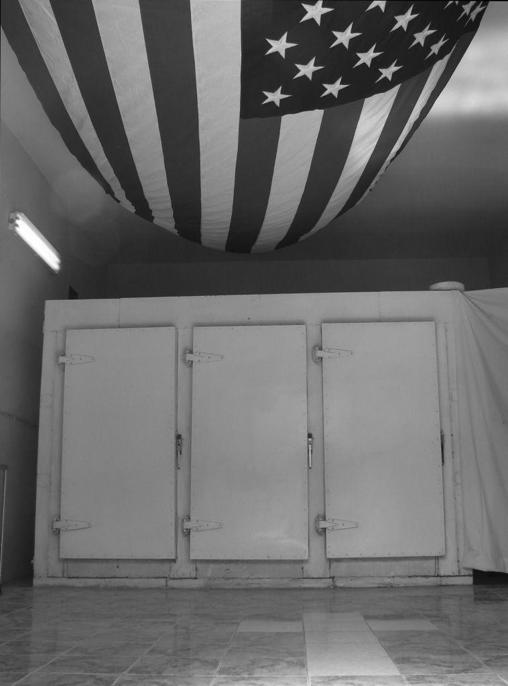

And then a welcome-home ceremony from a grateful nation in a small, half-filled gym.

It had been difficult getting everyone ready to go. Muqtada al-Sadr had reinstated his cease-fire as April began, but the attackers kept attacking anyway, which meant that even though full combat operations were over, the soldiers still out of the wire at COPs and checkpoints had to fight their way back to the FOB. At one point, in the operations center, where the movements were being coordinated, several soldiers watched incredulously on a video monitor as an Iraqi with an AK-47 jumped out from behind a building and began firing Rambo-style on a convoy. “Die, monkey, die!” Brent Cummings hollered for some reason, and the others began hollering it, too, laughing and chanting right up until the moment an Apache helicopter swooped in and blasted the monkey to smithereens, at which point they broke into cheers. At another point, they were monitoring a route-clearance team from another battalion that was moving up Predators toward some 2-16 soldiers at an abandoned Iraqi checkpoint. All of a sudden the screen went black, and when it cleared, the lead vehicle was curving off the road and accelerating through a field, the result of an EFP explosion that had decapitated the driver but left his foot in place on the gas pedal. All night long, Cummings continued to see that vehicle curving ever so gracefully into the field, and meanwhile Kauzla-rich had his own images to contend with in the form of another dream. This one had been about mortars. They were exploding everywhere. In front of him. Behind him. They kept coming, the bracketing bringing them closer and closer until the entire world was only noise and rising fire, at which point he had awakened and realized he was fine. He was absolutely fine.

“You are happy? Because you are leaving?” an interpreter asked Kauzla-rich now as she placed a call for him on a cell phone. She was substituting for Izzy, who had gone home to see if his family was safe.

“I don’t know,” he said.

“Okay. Qasim. Ringing.You want to talk to him?” she said.

Kauzlarich took the phone.

“Shlonek?”

he said (“How are you?”). And so it was that a few days later, Colonel Qasim and Mr. Timimi came to Rustamiyah to say goodbye to Muqaddam K.

“Kamaliyah?” Qasim said as they waited for an interpreter.

“No problem,” Kauzlarich said.

Qasim made a whooshing sound. Maybe he was trying to say missile. Maybe he was trying to say RPG. Maybe it was the sound of 420 of his 550 men deserting.

“Marfood.

Fucking guys,” Kauzlarich said.

“Hut hut hut hut hut,” Qasim said, imitating one of the expressions he had learned from Kauzlarich.

The interpreter arrived, giving Timimi the chance to tell Kauzlarich what had happened when Kauzlarich didn’t come to his rescue. “They burned everything,” he said. “Like savages, the things they did.” He was a humble man with a wife and two daughters, he said, and now he and his wife and daughters had nothing other than the clothes they were wearing. No house. No car. No furniture. Not even a pair of slippers, he said. He leaned closer to Kauzlarich. “I want just one thing from you,” he said in English. “If you can help me with money.” Then, moving away, as if being too close would make him seem like a beggar rather than a powerful administrator with an ornate desk and a cuckoo clock on a wall, he switched back to Arabic and asked for something else. “A letter saying he was working with you,” the interpreter said. “In case he goes anywhere for political asylum.”

Qasim’s turn. He, too, leaned toward Kauzlarich, but before he could ask for anything, Kauzlarich said he had something to give him and handed him a box. It didn’t say “Crispy” on top. There was no pizza inside. Instead, there was an old, polished pistol.