The Good Rain: Across Time & Terrain in the Pacific Northwest (36 page)

Read The Good Rain: Across Time & Terrain in the Pacific Northwest Online

Authors: Timothy Egan

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Travel, #Adventure, #History

With apples, the buyers from Safeway and A & P wanted a deep red that would hold its color for months past the harvest. Such a thing is impossible, unless helped along by chemicals. In time, like a coach secretly giving his best runner steroids, and feeling guilty whenever the athlete broke a record, the apple farmers of Washington started using Alar, and they experienced years of tremendous growth and prosperity. Salesmen from the chemical companies and big food chains convinced the farmers they couldn’t live without it, saying the consumer wanted a red that was nearly artificial in appearance instead of the duller, natural tone. Alar turned farmer against farmer; those who used it had a competitive edge over those who did not.

When researchers found that massive doses of Alar could cause cancer in lab rats, the market for Washington apples crashed, no matter the color or background of the fruit. Many of the small growers, some of the last of the nation’s family farmers, most of whom had never used Alar, were forced into bankruptcy. Others dumped their fruit or gave it to the homeless. They blamed a concerted media attack—“television terrorism,”

they called it—for their bad times. Never before had the apple, the very embodiment of good health, taken such a hit. Nobody claims to use Alar now. Mention of the word is like bringing up an old girlfriend in the presence of a new wife.

I pick through the rest of my duck, which has a pear glazing atop it. More fruit stories pour forth from the farmers. The first apple tree was brought to the Northwest by the Hudson’s Bay Company. The tree, planted at Fort Vancouver on the Columbia in 1825, still bears fruit.

“Betcha didn’t know that apples and roses come from the same family? You can even graft a rose onto an apple tree.”

The table goes silent. We pick at our teeth and food for a few minutes. A farmer sitting at the far end of the table speaks up for the first time tonight. “The Golden Delicious came from cow shit,” he says.

“No shit.”

“Cow shit,” says the fellow. “What happened was, a cow ate an apple and shit the seeds out. One of those seeds, carrying the strains of other apples, grew into the the first Golden Delicious.”

Granny Smith apples are the product of the garbage of a New Zealand woman who dumped rotting fruit in a creekbed. They grew up into trees which produced a tart, freckled green apple. She gave them away to her friends, who referred to the treat as “Granny Smith’s apples.”

It’s getting near bedtime for big Lowell. He’s expecting to make good money this year, after the disaster of last year, and is just scratching to get at the dawn. The only thing worse than the loss from overabundance was a long-ago freeze. Early November, twenty years ago, an arctic breeze scampered down through Canada along the Okanogan Valley into Washington, freezing up all the fruit trees while they still had sap in their veins. The sugar flow went hard, and expanded, causing the trees to literally explode.

“You could hear them pop, one after another—pop, pop, pop,” says Lowell. “Never seen anything like it. Lost most of the orchard.”

Following the Yakima River downstream toward the Columbia, I enter the wine country and a culture far removed from that of the apple growers. A person who harvests

vinifera

grapes for premium wine is not a farmer but an alchemist. Among the trellised vineyards, I hear music today, the sound of crush. At the Hogue family farms, across the railroad tracks along the river, the hops are recently in, the asparagus has been pickled, and now it’s time to make some wine. Great bunches of Cabernet Sauvignon

grapes are dumped into a vat, where they are crushed and the juice drained. From there, the juice goes to stainless steel storage and then to oak barrels and, in two years’ time, to the market—about three hundred cases of the most eagerly sought-after red wine in the Northwest. What sets the Hogue family vino off from the other wines of the world—aside from the taste, a high-acid Cabernet so crisp some people drink it with seafood—has to do with the volcanoes to the east, the snow atop them, and the far northern latitudes of this valley that was dismissed by Winthrop and other nineteenth-century prophets as useless.

Here, a few fruit farmers looking for crop diversification, aided by a handful of young hotshots from California, have gilded the Yakima Valley.

There are no stone cottages or elegant chateaus or pseudorustic tasting cellars in this part of the valley. For that matter, there is no history. This is a place of concrete apple juice warehouses and dry hills carved up by dirt-bike trails. On the same day that winemaker Rob Griffin is overseeing the crush of red grapes out in back, he has bottled a small rattlesnake which he found slithering around the front. Griffin slaps a Hogue Cellars label on the jar of the rattler’s new home. “It’ll be a good year for snakes,” he says.

In less than twenty years, the Pacific Northwest has become the greatest premium-wine-producing area in North America outside California. The wine growers here are not the peasants of Tuscany or the Ph.D. farmers of the Napa Valley. They are people like Wayne Hogue, a onetime sharecropper, then a hop farmer, now a genius. After working years for other people, he went out on his own with forty acres of hops in 1949. Over the decades he added spearmint, selling the mint oil to Wrigley’s, and Concord grapes, which he sold to Welch’s, and potatoes, which he sold to burger chains. Around the family dinner table at Christmas, the Hogues used to drink jug wine made by Mateus and toasted the new year with Andre’s Cold Duck champagne.

By the mid-1960s, a few small growers in the valley were starting to experiment with

Vitis vinifera

, the grapes that produce the world’s great wines. As a hedge against the highs and lows of crop prices, the Hogues planted ten acres of premium wine grapes in 1972, thinking maybe they could sell a few to the Californians during a down year for hops. The climate was right, with more than seventeen hours of daylight in June, a critical grape development period. The Yakima Valley has two more hours a day of sunlight than the Napa Valley during peak growing season. Looking at the globe, the growers noted that the Yakima Valley was located between the 46th and 48th Parallels, the same northerly latitude

as Burgundy and Bordeaux. With irrigation water, and the sun predictable, growing conditions can be tightly controlled, the grapes receiving the same amount of water as the French areas would receive naturally. Grapes ripened to full color in the long hot days, and gained enough acid for flavor in the cold nights.

The shot heard around the wine-producing world was fired in 1966 by André Tchelistcheff, considered the dean of California winemaking. He tasted a Washington Gewurztraminer and pronounced it the best in America. From then on, young graduates of the oenology school at the University of California at Davis began to look north.

“I came here with a genuine sense of mission,” says Griffin. “Everybody said, ‘Don’t go up there, Rob. It’s too cold in the winter for grapes to stay alive.’ I showed up in 1977, and there wasn’t much to look at. But all the ingredients for world-class winemaking were here—the soil, the climate, the water.” He started work at Preston Wine Cellars, down the valley near Pasco, seeking to develop a crisp, dry white. He came up with a Chardonnay and a Sauvignon Blanc that won so many admirers that when young Griffin showed up at the Dom Perignon cellars in Reims for a visit, he was welcomed at the champagne shrine as a celebrity from the wine-growing frontier.

“They’d actually heard of me, Rob Griffin from the Yakima Valley,” he says.

The Hogues hired Griffin in 1984, when the family decided to get serious about winemaking. The brothers, Gary and Mike, and their father, Wayne, sold their first vintages in the early 1980s from a roadside card table. Then a Chenin Blanc from that period won a gold medal at an international contest, and the Hogues were on their way. At first, they were uncertain about what to call their wine and how to market it. They were farmers, after all, not lawyers on a lark or urban exiles looking for a hobby and a tax haven. As Gary Hogue says, “I grew up with shit on my shoes.” The role model at the time was Chateau Ste. Michelle, a pioneer Washington winery known mainly for its Riesling, sold in all fifty states and throughout Europe and Japan. Recently, it was named the best vintner in America. But the Hogues were uncomfortable with French-sounding pretense for a Washington wine.

“There aren’t any chateaus here,” says Gary Hogue. “I doubt if there’s a building older than a hundred years in this valley. We didn’t want to be something we weren’t, some Euro-winery or whatnot. We figured what we had here was crisp and clean and fresh, like the country here. Finally, we just put our names on it—Hogue Cellars, Yakima Valley wine. Wine

is such an ego thing; it’s the only crop where you can follow it all the way through the chain and stand in front of people and say, ‘How do you feel about this?’ ”

At the same time, up the river from Hogue, a former New York attorney named David Staton was starting to turn out Chardonnays and Rieslings that were beating all California whites in national wine-tasting contests. The Riesling of Washington has enough acidity to balance the grape’s natural sweetness, an original taste. In Oregon, the Pinot Noirs from the Willamette Valley were causing Frenchmen to scramble to their maps of North America. Staton, with winemaker Rob Stuart, another Cal Davis graduate, pioneered a vineyard trellising method that allowed more air to circulate around the grapes and gave them maximum sun exposure. As a hedge against winter freezing, he came up with a drip irrigation system that forced the roots to go deep for water rather than spread out along the surface. In the alluvial Yakima Valley, he found that roots could go thirty feet down and still be in rich soil. At one time, he thought the best hope for American winemaking was in California. No more. The temperature variations of the Yakima Valley—a fifty-degree drop from noon to midnight is not uncommon in the spring and fall—were perfect for full-flavored grapes. By comparison, he says, California wines are flat and overripe.

The future is in red grapes. The biggest problem the Hogues had with their Merlot and Cabernet Sauvignon last year was keeping it in stock. Recently, the hop farmer’s 1985 Cabernet Sauvignon Reserve was chosen the Best of the Show from among two thousand entries at the largest international wine competition in the country. A few years earlier, when the brothers tried to peddle their wine at the finer restaurants in Seattle, they were told to go away and take their stinking fruit and berry wine with ’em.

Griffin talks like a true evangelist. “Everybody thought the Mount St. Helens eruption was going to kill the Yakima Valley wine industry. We got three inches of ash on the ground here. The sky went completely dark. But the best grapes are planted in the worst soil. They’ll tell you that in France. Volcanic soil drains better than anything. It’s not fertile. It’s sterile. It’s silica, what they use to make glass. But all you need is a good medium.”

As the color of an October day gives way to the soft tones of night, Gary Hogue cracks a year-old Chardonnay. We sit outside and watch the light shrink on the Rattlesnake Hills, and listen to the last sounds of harvest. We are surrounded by the best products of the earth at this

latitude, under the benign influence of these volcanoes and the life-giving water from the Naches and the Yakima. Theodore Winthrop looked around and saw a fallow basin; I think of the Yakima Valley as a young bride at the altar, about to begin a full life. Hogue, dressed in plaid shirt and workboots, keeps asking me what I think of his Chardonnay. The bottle is nearly empty now, and I’m not sure how to describe it. I review all those wine terms: should I say it has a delicate aroma, with a complex but subtle bouquet, outstanding clarity, well-shaped body with just the right touch of vinosity, or should I talk up the acidity and residual sugar? We drain the bottle, and I turn to Hogue.

“It tastes like the Northwest.”

Chapter 12

G

OD’S

C

OUNTRY

C

ANCER

A

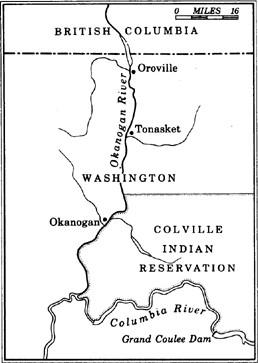

hard wind from the north delivers the first blast of winter to the Okanogan Valley this morning, a few days into November. Along the road that follows the river, migrants hitchhike for rides south. The apples have all been picked; those that remain belong to the deer and the frost. I follow the Okanogan River north from its confluence with the Columbia, searching for people who were here in the fall of 1963, when much of the world looked to the apple farmers and ranchers of this remote country to render judgment on a time of hysteria. Many of the people I want to see are dead. Others have moved away. To live in this valley, bordered by the dry edge of the North Cascades on one side and the forested expanse of the Colville Indian Reservation on the other, where the summers burn hot all day and the winters bring isolation,

requires an emotional commitment that few people can remain faithful to for life.

When I start to knock on doors and introduce myself, people smile and tell their dogs to stop barking. But when I say I’d like to talk about what happened to the Goldmark family—John and Sally and the kids—the response is the same: We’d rather not discuss that. At one home in Malott, a riverside village of perhaps two dozen people, the old woman I wish to speak with slams the door in my face.