The Good and Evil Serpent (78 page)

Read The Good and Evil Serpent Online

Authors: James H. Charlesworth

Fourth,

the narrator does not depict the serpent—and the serpent alone—as fully responsible for all the evils in the world

. The serpent does not force the woman to appreciate the forbidden fruit, take it, and eat it. The author does not primarily intend to explain the origin of sin and evil.

224

Yet, long before 70

CE

, Jews interpreted Genesis 3 as an explication of the origin of sin. The ancient people of the Book saw no problem with the two accounts of how evil and sin appeared on this earth: the serpent and woman in Eden (Gen 3) and the fall of the angels (Gen 6; cf. esp.

1 En)

. Probably many Israelites and Jews imagined that the two accounts could be conflated. Most likely some early Jews imagined that the “serpent” was originally a fallen angel.

Fifth,

the narrator clearly states that the serpent was one of God’s creatures

. As snakes often do in homes near the equator, on hiking outings, or in forests, the serpent appears suddenly and mysteriously. There is no introduction. In a moment, the serpent is present in the narrative. Once present, he acts or speaks. The narrative thus embodies the symbol of the serpent as being swift and elusive (cf. Pos. 3). The serpent does not come with the announcing roar of a lion. It does not arrive with the trumpeting of an elephant, or the pounding hoofs of a horse. It comes silently and unexpectedly. The serpent’s ability to symbolize swiftness and elusiveness is reflected in the Eden Story. One thinks about the metal serpents, which are abundant now from ancient Palestine. They have numerous curves, and usually the head is shown upright.

Genesis 3:1 thus introduces the serpent abruptly; there is no transition from what precedes. The “serpent” had not been mentioned before; it is suddenly present in the narrative. It is one of God’s creations, but the reader is not prepared for the appearance of the serpent and the resulting story. While there are echoes in Genesis 3 of previous verses, there is no foreshadowing of the serpent by the Priestly Writer in Genesis 1:1–2:4a, or by the Yahwist in 2:4b-3:1.

Sixth,

the Nachash was not depicted as ugly or as a horrible-looking animal

. The Nachash in fact appears without any description. We may assume he has legs because of God’s curse on him, but we are not told how the Nachash looks. He must have a mouth and a larynx since he talks with the woman. We are not told if he has eyes, as one might assume from the study of ancient Near Eastern serpent iconography (but there are also images of snakes without eyes). We do not know if the Nachash has a nose or scales. We do not know how tall the Nachash is or what he looks like. Perhaps this is intentional, since what is important are the serpent’s wisdom or cunning and ability to talk with the woman. Most likely, not only did the Yahwist know that a full description would detract from the reader’s ability to grasp his important point, but “serpents” were very familiar in life, image, and myth to his audience.

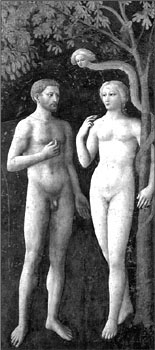

Figure 79

. Adam and Eve, According to Masolino in the Cappella Brancacci. JHC

Seventh,

we may assume the serpent is probably a male, but he has no sexual approach to the woman

. There is no evidence that the serpent entices the woman, and the assumption that the serpent uses some erotic powers to entrap her comes out of the misguided imagination of the modern person. There is no evidence that the serpent is first and foremost a phallic symbol (Neg. 16 or Pos. 1).

A study of how gifted artists depict Adam,

225

the woman, and the serpent is revealing. Unlike exegetes, artists must decide if the serpent is male or female, in the tree or beside it, beautiful and appealing or ugly and disgusting.

226

To demonstrate the paradigmatic difference between artists and exegetes—one would hope that this ceases to be the rule—only a few select illustrations must suffice. The most riveting might be Masolino’s painting in the Capella Brancacci in Florence. Note how feminine and appealing the serpent is depicted in the painting.

227

The serpent is inviting, clean, and intelligent looking. She and the woman are closely related to the tree and appear as virtual twins.

The depiction of the serpent as feminine and similar to the woman is exceptional, but not unique. In 1508, Raphael, when he was about twenty-five, painted on the walls of Pope Julius II’s study in the Vatican a serpent that is angelic and cherubic. It is close to “the woman,” and one is given a sense of tranquility as the friendly serpent winds its way up the tree. Adam’s right hand and the woman’s left hand are depicted moving up toward the serpent. Raphael seems to have influenced Michelangelo, who also presented the serpent with an appealing, even feminine, face.

Michelangelo thus depicted “the serpent” in Eden as a woman. The Nachash is similar to “the woman” except that her torso, as in Masolino’s masterpiece, is a serpent, and it likewise winds around the tree. In Michelangelo’s art, as in Raphael’s masterpiece, both Adam and the woman are reaching up toward the serpent.

228

Finally, in the Strasbourg Cathedral and in St. Catherine’s Chapel, which was completed in 1349, there is a depiction of Adam and “Eve” (at that point in the narrative she is “a woman” and not yet Eve) with a serpent. The creature also has a feminine face. The crucifixion above them, based on the Fourth Gospel, is a depiction of Numbers 21.

These artists rightly perceived the attractiveness of the serpent. None of them, however, knew enough about ancient serpent iconography to depict the serpent upright, with hands and feet, and conversing animatedly with the woman. They did, nevertheless, bring out in their portraits of the Nachash the attractive features of the human in God’s creation.

These later artistic renderings of the Genesis story must not influence our reading of Genesis 3. In the Hebrew text, the

nachash

is a masculine noun. The verbs associated with him are masculine. Though the wise creature is often depicted as a female, that should not be the guiding principle in studying the Nachash in Genesis 3. The creature seems to be male, both grammatically and conceptually in the Hebrew Bible. Moreover, images of serpents in ancient Palestine about the time of the Yahwist depict the serpent as a male (or at least devoid of feminine features).

Eighth, it should now be obvious that

the author of Genesis 3 does not depict the serpent as beastly

. The serpent does not have the features of an ugly beast. The imagined shape of Satan, especially in medieval Christianity, must not be imposed on the image of the serpent in Genesis 3. The woman speaks with the creature; that should indicate that she is not afraid of the animal nor finds it repulsive.

Ninth,

can one really be certain that

, before the serpent spoke with “Eve” (she is not named until 3:20),

all was peaceful in Eden?

It seems too imaginative and romantic to surmise that in Eden the male and female walked with God, together, in the cool of the evening. How much harmony was there, at the beginning, in creation? Did not the Creator’s prohibition of Adam to eat from the fruit of the tree in the middle of the garden cause some tension? If Adam was human, was he not tempted by the Creator’s prohibition? Since the human was bereft of knowledge and the forbidden fruit was not on a tree on the edges—but in the center—of Eden, did God not make it virtually impossible for the human to obey the commandment? Was Adam not like Paul who found that prohibitions became temptations (Rom 7–8)?

How peaceful and idyllic was Eden? What kind of an Eden can be bereft of knowledge? In apocalypticism, we might imagine that the Jewish author sought at the End-time a return to the First-time. This repeated cliché derives from Gunkel’s claim that the

Endzeit wird Urzeit

, “the Endtime shall be (a return to) the Firstime.” However, there are major differences: there is no commandment, and there is no foreboding future of disobedience with another disastrous distance between the human and others, nature, and the Creator. Moreover, if the first Eden depicts a human without any knowledge or experience of good and evil, the final Eden imagined by Jewish apocalyptic writers results from the human’s experience of good and especially evil. There cannot be a return to a dialogue with a Nachash since God’s curse on him was irreversible, as the Jewish sages knew and stressed.

Tenth,

no one should imagine that the serpent alone is responsible for the entrance of sin into creation

, the appearance of death, and the cause of punishment and ultimately of banishment. The one who compiled the story in Genesis 3 shared the blame with all—the woman, the man, and the serpent. That is why all three were punished by God. The narrator would have been surprised that he allowed for some blame to reside even with God, not only in the statement that the serpent was created by God, but also in God’s prohibition to eat from the fruit of one tree. Thus, the Yahwist avoids an error that sometimes appears in apocalypticism: the infinite separation of the created from the Creator. God was also included in the drama; after all, if God had not provided a prohibition, there would have been no possibility of disobedience.

Thus, by focusing on the symbol of the serpent in Genesis 3, we become sensitive to contradictions in Christian theology and the age-old misinterpretations of the story of Eden. God is the creator of all, even the Nachash—a beast of the field who becomes the serpent. If the definition of truth is what God states, then God spoke the truth in Eden. If, however, truth is defined by relationships, then what happened is not what God predicted: the humans do not drop dead immediately; they obtain knowledge of (and experience) good and evil. Perhaps the Yahwist attempted to bring God into the world of humans and to make God one with whom humans could have a covenant relationship. The Yahwist put human qualities on God. He portrayed God as apparently lying and not knowing what would happen when the woman, or anyone, ate from the forbidden fruit. According to the Eden Story, God also seems to have lost touch with the human, calling out to Adam: “Where [are] you?” (Gen 3:9).

It is not correct to claim that God did not make demands on the first humans (the protoplasts). The Yahwist pointed out that the Creator always comes to us as one who makes demands. According to the narrative, the Creator seems also responsible for the so-called Fall. The story binds the Creator to his creatures. The story is complex, somewhat inconsistent, but its main point comes home: sin (and evil) is disobeying God. According to the Yahwist’s composition, God is not distant and categorically above human aspirations, like telling the truth and being consistent. Yet, in mysterious ways, God and the serpent represent another dimension of reality.

The Yahwist shows an inordinate amount of interest in and fascination with the serpent. The Nachash once spoke clearly and wisely, and he presumably walked. Now the snake has no eyelids to protect it from the sun or dirt. It no longer can speak or hear (it has no ears [the one who gave us Ps 58:5(4) seems to err and assume a snake can hear]). It now must crawl on its belly and be fearful of any relation with the human, who may crush it. According to the

Midrash on the Psalms (Midrash Tehillim)

, which probably reached its present shape in the ninth century

CE

, there is a deep meaning in Psalms 58:5–6. Note this exegesis attributed to David, who composed the Psalms, according to ancient traditions: “David said further to them: Know ye not what the Holy One, blessed be He, did to the serpent [ ]? He destroyed his feet [

]? He destroyed his feet [ ] and his teeth so that the serpent now eats dust.”

] and his teeth so that the serpent now eats dust.”

229

According to this same text, if the snake still had feet: “It could overtake a horse in full stride and kill him.”