The Good and Evil Serpent (135 page)

Read The Good and Evil Serpent Online

Authors: James H. Charlesworth

Appendix III: Anguine Iconography and Symbolism at Pompeii

August 24, 79

CE

, was a fateful day for the inhabitants of Pompeii and its environs. These Romans, as they headed toward their tasks while looking up to a blue sky and bright sun, would never again see a peaceful sky. Their frescoes, paintings, and gold jewelry remain. As we look at them, it becomes clear how much has changed, especially regarding anguine symbolism. Almost two thousand years later, we can pause and remember that horrific day, as we look at the outlines of their gray remains. Some Pompeians remind us how to die; for me especially poignant are the lovers who did not flee into the inferno, deciding to “go out” holding on to what was most dear.

About a decade earlier, in June 68

CE

, the Qumranites also faced a tragic day. These Jews who gingerly placed over seventy scrolls in jars and on rocks inside what we call Cave I would never see the scrolls again. Many of these Jews scampered up the limestone cliffs, heading west to find safety behind the walls of Jerusalem. Some may have paused, and looking backward would have seen Vespasian astride a horse prancing before a massive tower behind which a community went up in flames. What the Qumranites hid in Cave I have become some of our greatest treasures from antiquity. These Dead Sea Scrolls contain ideas and perspectives we humans have not yet understood and practiced. They mirror minds who found secrets about the spiritual that still elude many of us.

Only eleven years separate these monumental events in our past. Both Pompeii before 79 and Qumran before 68 had been devastated previously by earthquakes. Pompeii was hit in 62

CE

and Qumran in 31

BCE

.

1

As N. Purcell states about Pompeii: “[T]he sudden destruction crystallized a problematic moment: the damage of the earthquake of 62 was still being patchily repaired and the opulence and modishness of some private and public projects of the last phase … contrast with chaos and squalor.”

2

At Pompeii, and also at Qumran, there are vivid reminders of an earthquake that antedates the final destruction.

It is conceivable that one or more persons witnessed both horrors, the one in Judea in 68 and the other in Campania in 79. Perhaps one who had worked in the Qumran Library also slaved in the Herculanean Library known as “the Villa of Papyri.” Why are these reflections not simply outlandish fantasies?

The Hebrew graffiti being found on the western slopes of Vesuvius, especially at Pompeii and Herculaneum, are often left by Jewish slaves. The inscriptions are “recent”—they were made shortly before 79. The Hebrew is common and unskilled, probably written by uneducated Palestinian Jews. Their vulgarity contrasts with the elegant and refined Hebrew in most Qumran scrolls.

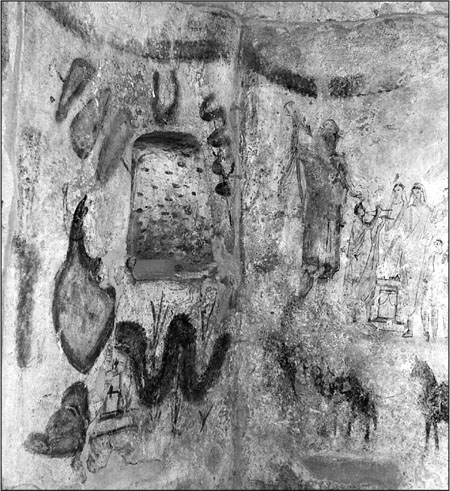

Figure 88

. The House of Criptoportico, Close-up. Pompeii. JHC

Jewish slaves were certainly brought to Italy when Jerusalem fell in 70

CE

. Hebrew scrolls are known to have been seen in Rome in the decades after 70 and they contain readings now being found in the Dead Sea Scrolls. Josephus tells us that he was allowed by Titus to take scrolls that were in the Temple (see his

Life).

3

One cannot refrain from wondering: “Were any of the Jewish slaves in Italy, especially at Pompeii, originally Qumranites?” Vespasian, who burned Qumran, enjoyed vacationing in the area highlighted by Cuma (and the Grotta della Si-billa),

4

Quarto, Puteoli, Baia, Capo Miseno, Neapolis [Naples], Herculaneum, and Pompeii. A temple to Vespasian was erected on the southern side of the famous forum in Pompeii. Did Vespasian in Campania ever recognize a face he had seen at Qumran or in Palestine? The answer is “probably no.” But one cannot be certain, and good historicity requires such imaginative reflections.

Is it foolish to compare Roman Pompeii and Jewish Palestine? Again the answer is clear: “certainly not.” Trade had long united the two areas, and the relation seems to have increased before 70

CE

, when Titus took Jerusalem. Trade between Campania and first-century

CE

Palestine has become palpably evident. The so-called “Pompeian-red” ware has been found in Samaria and elsewhere in ancient Palestine. Excavators working in Jerusalem recently discovered Pompeian rim forms. Their date is singularly important for us. Why? The answer lies in the recognition that the wares date from the time of Augustine to the end of the first century

CE

.

5

That covers the period in present focus.

Many who have written on Pompeii stress the extreme distance between rich and poor. The houses of the wealthy in Pompeii are often more opulent than posh apartments in Manhattan; they were decorated with frescoes and elegant bronzes that make the modern usually pale into mediocrity. The average houses are frequently far better than the tenant apartments that multiply in and around New York City. Thus, contrasts must be understood in terms of contexts. Pompeii was a place for the wealthy; I know of no dwelling there that should be categorized as a dwelling for the abjectly poor.

Figure 89

. House of the Hebrew. Pompeii. JHC

A closer look at the remains of pre-79 Pompeii reveals something astounding. Serpent images are seen on private “chapels” in homes, in public thoroughfares, and especially on gold rings, bracelets, earrings, and armlets.

Larari with Serpents

. In Pompeii and elsewhere in the Roman world, larari are featured in houses and homes. They are essentially little chapels and small shrines that remind me of a similar modern practice. Today, outside Pompeii in all directions I frequently see niches outside houses; these are for honoring the Virgin Mary. The human perpetuates the need for divine presence and protection.

The

larari

represent the domestic cult. They were destined to ensure the prosperity, health, and continuity of the household. Romans focused religion on household gods and ancestors.

In houses, the

larari

habitually feature elegant images of serpents.

6

Only a selection may be presented now.

7

In “the House of Criptoportico,” in the

lararium

of the peristyle, are depicted three ophidian images: a large Agathadaimon,

8

a serpent encircling an altar (or fountain) then rising above it, and a depiction of Hermes with the caduceus (I-16–2).

The “House of Menandro,” so called for the presence of a fresco of the poet Menandro, was restored recently by A. De Simone. The house has in the atrium, on the right, a

lararium

with an interesting representation of a snake, but it is not Agathadaimon. The monumental form of the

lararium

is an index of the wealth of the owners. This house belonged, in fact, to a

libertus

of the family of Poppea, the wife of Nero. There are undeniable signs of the inhabitant’s wealth. For example, the house has expensive mosaics crafted from tiny tesserae, and archaeologists found 130 pieces of an opulent silver service for sumptuous dining.

Figure 90

. House of the Pig; Shrine to Asclepius. Pompeii. JHC

On the wall in front of the entrance to the House of Menandro, on the left, we may admire a scene of Laocoon with his sons, the snake (

dragon

), and the sacrifice of the bull. Not only Greek mythology but Jewish traditions left impressions on those who frequented the house. Near the garden, images represent biblical scenes (e.g., the Judgment of Solomon) with exotic characters as dwarves and pygmies. Moreover, one can examine the “images of the ancestors” (

immagines maiorum

) in wood.

The “Two Plans House,” also called the “House of the Hebrew,” was built during the Neronian Period. Particularly interesting is a fresco, in front of which is an altar. Featured in the fresco are two Agathadaimons, an egg, and fire.

A snake with an egg also is seen in Region I, insula 11, entry 10. The depiction of a serpent with an egg and before an altar clarifies that the serpent symbolizes something desirable and positive, perhaps fruitfulness (Pos. 2), creation (Pos. 7), the cosmos (Pos. 8), chronos (Pos. 9), divinity (Pos. 11), and rejuvenation (Pos. 26).

In Region I, insula 16, entry 4 (179), is a

lararium

featuring two snakes. Also, in Region I, insula 16, entry 3, one can see, in stucco, an embossed snake.

In Region I, insula 11, entry 8, one may see another impressive fresco. Most interesting for us is a depiction of Hermes (Mercury) with the caduceus, and a priest with the

praetexta

robe. He brings in his hands the horn of abundance, a

lares

with horn, and wine in a bucket. Below him are shown two snakes. In the “House of the Pig” is a painting of a snake and a pig. There is also a shrine to Asclepius.

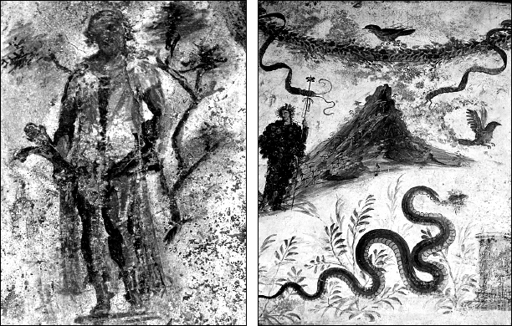

Figure 91

.

Left

. Priapus. Pompeii. JHC

Figure 92

.

Right

. Bacchus, Agathadaimon, and Vesuvius. Pompeii. JHC

In “the House of the Vettii,” in the central panel of the

triclinium

, is a painting of Hercules, as a lad, strangling two serpents.

9

In the “House of the Criptoportico,” already mentioned because of its

lararium

, is a painting of Hermes (Mercury) with the caduceus and the snake.

The “Brothel House” at Pompeii attracts a long line of visitors. Yet most of them do not see the picture of Priapus, inside the door, above and to the right.

10

He has two phalli, and he holds each in his hand. What could be the meaning of this symbol? Is it a male fantasy to double penetrate a prostitute? Is it a sign of double power and fertility?