The Golem (12 page)

Authors: Gustav Meyrink

Tags: #Literature, #20th Century, #European Literature, #v.5, #Amazon.com, #Retail

Crowded together in rows and with their fur caps pulled tight down over their ears, the children were staring up open-mouthed and listening spellbound to the verses of the Prague poet, Oskar Wiener, that my friend Zwakh was declaiming from inside the booth:

What have we here? A jumping jack!

As skinny as a rhyming hack;

All dressed in rags of red and blue –

Watch the tricks that he gets up to.

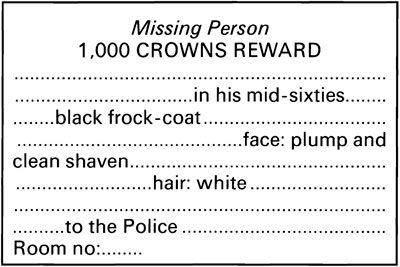

I turned down the dark, twisting street that led to the square. A packed, silent crowd was standing shoulder to shoulder in the darkness in front of a notice. One man had struck a match and I managed to read odd words here and there which registered dully in my consciousness:

Void of interest in my surroundings, void of all desire, I slowly went on into the darkness between the rows of unlit houses, a living corpse. A handful of tiny stars glittered in the narrow strip of sky above the gables.

At peace now, my thoughts went back to the Cathedral, and the calm that encompassed my soul became more blissful, more profound. All at once, from the square came the voice of the puppeteer, crystal clear on the wintry air, as if it were close to my ear:

Where is the heart of coral red?

It hung upon a silken thread,

Gleaming in the blood-red dawn.

Until deep into the night I paced restlessly up and down my room, tormenting my brain to find some way of helping ‘her’. Often I was on the point of going down to Shemaiah Hillel, to tell him everything that had been confided to me and to ask him for advice, but each time I rejected the idea.

I saw him towering so high above me in the spirit, that it seemed a desecration to bother him with practical matters. Then again, there were moments when I was racked with doubt as to whether I really had been through all those happenings which, although only a brief span of time separated them from the present, now seemed so strangely faded compared to the throbbing vitality of my experiences of the last few hours.

Was it not all a dream? How could I, a man who had suffered the outrageous misfortune of forgetting his past, accept as fact, even for a moment, something for which my memory was the only witness on which I could call? My glance fell on Hillel’s candle, which was still on the chair. Thank God! I had been in personal contact with him; that at least was one thing I could be sure of. Should I not abandon all this introspection and rush straight down to him, clasp his knees and pour out the excruciating anguish that was eating away at my heart?

I already had my hand on the latch, but then I let go of it. I could see what would happen: Hillel would gently pass his hand over my eyes and – no, no, not that! I had no right to ask for relief. ‘She’ had put her trust in me and in my help and if, at the moment, the danger she feared appeared small and insignificant to me, it certainly seemed enormous to

her

.

Tomorrow would be time enough to ask Hillel for advice. I forced myself to look at the matter coolly and objectively. Should I go and disturb him now, in the middle of the night? Impossible! It would be the act of a madman.

I was going to light the lamp, but then I let it be. The reflection of the moonlight from the roofs opposite shone into my room, making it brighter than I needed. I was afraid the night would pass even more slowly if I lit the lamp. There was a sense of hopelessness about lighting the lamp just to await the morning; a vague fear whispered that that would make the dawn recede until I should never see it.

I went over to the window. The rows of ornate gables were like a ghostly cemetery floating in the air, weatherworn tombstones with eroded dates erected above the dark vaults of decay, those ‘dwelling-places’ where the swarms of the living had gnawed out caverns and passageways.

For a long time I stood there, staring out into the night, until I gradually became aware of a feeling of surprise nibbling gently at my consciousness: why was I not trembling with fear when I could clearly hear the sound of cautious steps from the other side of the wall?

I listened. There was no doubt about it, someone was out there again. The brief groans from the boards betrayed each hesitant, creeping step. At once I was fully alert again. Every fibre in my body was so concentrated in my determination to hear that I literally grew smaller. All my sense of time was focused on the present.

A brief rustling that broke off short, as if startled at itself, then deadly silence, that agonising, watchful hush, fraught with its own betrayal, that stretched each minute to an excruciating eternity. I stood there, stock-still, my ear pressed against the wall, with the ominous certainty rising in my throat that someone else was standing on the other side, doing just the same.

I strained my ear – nothing.

The studio next door seemed utterly deserted.

Silently, on tiptoe, I stole over to the chair by my bed, picked up Hillel’s candle and lit it. Then I stood there, working out what I was going to do. The handle of the iron door in the corridor that led to Savioli’s studio was on the other side. I picked up the first suitable implement that came to hand, a wire hook that I found on the table among my engraving tools. That kind of lock was easy to open, all it needed was one touch on the spring.

And then what would happen?

I decided that it could only be Aaron Wassertrum next door, prying around, perhaps rummaging through cupboards and drawers to find more evidence, more weapons in his fight against Savioli. What good would my interrupting him at it do?

I did not waste much time in thought. Action, not reflection, was what was needed! Anything to put an end to this terrible wait for morning to come!

The next moment I was standing by the iron door. I pushed at it, then carefully inserted the hook into the lock, listening all the time. Yes! From inside the studio came the scraping sound of someone pulling out a drawer.

The next moment the bolt shot back.

Although it was dark and my candle only dazzled me, I had a view of the whole room. A man in a long black coat started up in panic from a desk, hesitated for a second, uncertain what to do, took one step forward, as if he were going to hurl himself at me, then snatched his hat from his head and swiftly covered his face with it. I was about to demand what he was doing here, but he forestalled me. “Pernath? Is it you?! For God’s sake, get rid of that light!” I seemed to recognise the voice; it certainly wasn’t Wassertrum’s.

Automatically I blew out the candle.

The room lay in semi-darkness, dimly lit, like my own, by the shimmering haze from the window, and I had to strain my eyes to the utmost before I could recognise in the emaciated face with the unhealthy red blotches that suddenly appeared above the coat, the features of the medical student, Charousek.

“The monk!” were the words that came to my lips, and all at once I comprehended the vision I had had yesterday evening in the Cathedral.

Charousek! That was the man I should turn to!

And I heard once again the words he had spoken while we were sheltering from the rain in the house entrance, “Aaron Wassertrum will soon find out that there are those who can pierce the vital artery with poisoned needles through solid walls. Soon, on the very day he thinks he has Dr. Savioli at his mercy!”

Had I an ally in Charousek? Did he know what had happened as well? The fact that I had found him here, and at such an odd hour, suggested as much, but I was loth to ask him straight out. He had rushed over to the window and was peering through the curtains down into the street. I guessed that he was afraid Wassertrum might have seen the light of my candle.

After a long silence he said, in an unsteady voice, “You probably think I’m a thief, Pernath, finding me here, at night, in someone else’s apartment, but I swear to you –”

I interrupted immediately to reassure him. To show that I did not distrust him at all but saw him, on the contrary, as an ally, I told him everything – with the few reservations I thought necessary – about the studio and that I was afraid that a lady who was a close friend of mine was in danger of falling victim, in some way or other, to blackmailing demands from the rapacious Wassertrum. From the polite way he heard me out, without putting any questions, I deduced that he already knew most of it, even if not the precise details.

“So it’s true”, he muttered to himself when I had finished. “I was right after all. The fellow intends to ruin Savioli, but hasn’t enough evidence yet. Why else would he spend all his time snooping round here? You see,” he explained, when he saw my puzzled expression, “yesterday I was walking – let’s say ‘by chance’ – along Hahnpassgasse when I happened to notice Wassertrum strolling up and down, with feigned nonchalance, outside the entrance to this house; the moment he thought no one was looking, he quickly slipped into the building. I immediately followed and pretended to be visiting you; that is, I knocked at your door, and as I did so I caught him trying a key on the iron door to the roof space. Of course, he stopped the moment he saw me and used the same pretence of knocking at your door. You don’t seem to have been in.

Cautious enquiries in the Ghetto revealed that someone – and from the descriptions it could only be Dr. Savioli – had a secret love-nest here. As Savioli is seriously ill, I could work out the rest for myself. See, I’ve taken these from the drawer, to thwart Wassertrum”, he said, pointing to a packet of letters on the desk. “They’re the only papers I could find, let’s hope I haven’t missed any. At least I’ve had a good look through all the chests and cupboards, as far as it’s possible in this darkness.”

As he was speaking, my eyes searched the room and were caught by the sight of a trapdoor in the floor. I vaguely remembered Zwakh telling me some time or other that there was a secret entrance to the study from below. It was square and had a ring as a handle.

“Where shall we keep the letters?” asked Charousek. “I should imagine you and I, Herr Pernath, are probably the only people Wassertrum thinks are harmless, me because … well … there are … particular reasons for that” (his features were twisted in an expression of violent hatred as he spat out those last words) “and you he considers …” Charousek choked back the word ‘mad’ with a hurried and obviously feigned fit of coughing, but I guessed what he had been going to say. I was not hurt by it. I felt so happy at the idea of being able to help ‘her’ that my sensitivity to such suggestions had completely vanished. We decided to hide the packet in my room and went back there through the iron door.

Charousek had left a long time ago but I still could not make up my mind to go to bed. A sense of unease was gnawing at me, making rest impossible. I felt there was still something I had to do, but what was it? What?

Make a plan of our next moves for Charousek? No, that alone wasn’t enough. He wouldn’t let the junk-dealer out of his sight for one second anyway, of that there was no doubt. I shuddered at the memory of the hatred emanating from his every word. What on earth could it be Wassertrum had done to him?

This strange sense of unease inside me was growing, driving me to distraction. There was something invisible calling me, something from the other side, and I could not understand it. I felt like a horse being broken in: it can feel the tug on the reins, but doesn’t know which movement it’s supposed to perform, cannot tell what is in its master’s mind.

Go down to Shemaiah Hillel?

Every fibre in my body resisted the idea.

The vision I had had in the Cathedral, when Charousek’s head had appeared on the monk’s body in answer to my mute appeal for help, was indication enough that I should not reject vague feelings out of hand. For some time now hidden powers had been germinating within me, of that I was certain; the sense was so overpowering that I did not even try to deny it. To

feel

letters, not just read them with my eyes in books, to set up an interpreter within me to translate the things instinct whispers without the aid of words: that must be the key, I realised, that must be the way to establish a clear language of communication with my own inner being.

‘They have eyes to see, and see not; they have ears to hear and hear not’; the passage from the Bible came to me like an explanation.

“Key … key … key …” As my mind was teasing me with these strange ideas, I suddenly noticed that my lips were mechanically repeating that one word. “Key … key …?” My eye fell on the wire hook which I had used to open the door to the loft, and immediately I was inflamed with the desire to see where the square trapdoor in the studio led. Without pause for thought, I went back into Savioli’s studio and pulled the ring on the trapdoor until I had managed to raise it.

At first, nothing but darkness.

Then I saw steep, narrow steps descending into the blackness. I set off down them, but they seemed never-ending. I groped my way past alcoves damp with mould and mildew, round twists, turns and sharp corners, across passageways leading off ahead, to the left or the right, past the remains of an old wooden door, taking this fork or that, at random; and always the steps, steps and more steps, leading up and down, up and down, and over it all the heavy, stifling smell of soil and fungoid growth.