The Golden Flight

Authors: Michael Tod

THE GOLDEN FLIGHT

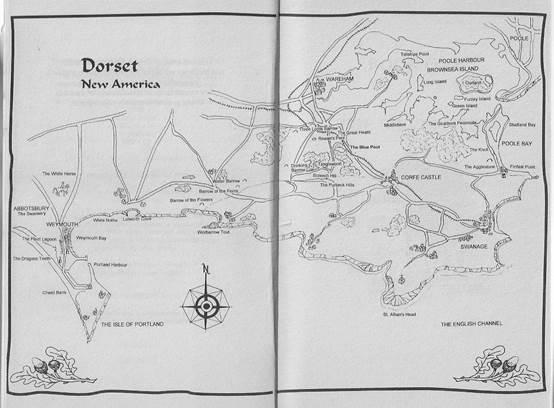

Book Three in The Dorset Squirrels Saga

by

Michael Tod

About the author:

Novelist, poet and philosopher Michael Tod was born in Dorset in 1937. He lived near Weymouth until his family moved to a hill farm in Wales when he was eleven. His childhood experiences on the Dorset coast and in the Welsh mountains gave him a deep love and a knowledge of wild creatures and wild places, which is reflected in his poetry and novels.

Married with three children and three grandchildren, he still lives, works and walks in his beloved Welsh hills but visits Dorset whenever he can.

PUBLISHED BY:

Cadno Books

The Dorset Squirrels Saga

Copyright © 2010 Michael Tod

This book,

The Golden Flight

, is available in print at

michaeltod.co.uk

as part of The

Dorset Squirrels Saga

in a single volume with

The Silver Tide

and

The Second Wave

.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise) without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, brands, media, and incidents are either the product of the author's imagination or are used fictitiously. The author acknowledges the trademarked status and trademark owners of various products referenced in this work of fiction, which have been used without permission. The publication/use of these trademarks is not authorized, associated with, or sponsored by the trademark owners.

CHAPTER ONE

March 1964 roared in upon Dorset.

The great sweep of the Chesil Bank in Dorset was taking the full force of the south-westerly gale as a deep depression drove in from the Atlantic. For over twenty miles pebbles snarled and ground as the heavy seas rushed in, each wave tumbling over the previous one in its haste. The churning action rounded the stones and moved them ever eastwards, sorting the pebbles by size as they trundled along. To the west the shingle was pea-sized, whereas at the aptly named Deadman’s Bay at the Portland end of the beach, it ranged in size from that of a potato to that of a giant swede.

By nightfall the waves were breaking over the crest of the Bank and rushing down the far side, tearing out the mats of sea campion that grew on the landward slope above the more sheltered waters of the Fleet Lagoon.

The usually smooth surface of the Fleet was choppy and debris-laden as gusts of wind carried plastic bottles, fishing-net corks, small pieces of driftwood and dead seaweed from the Chesil Bank and tossed them all into the Lagoon behind.

Where Mute swans had nested on the mainland side of the Fleet for over six hundred years, a flock now huddled on their nest sites, heads tucked under their wings to keep dust and flying reeds from their eyes.

There was no rain, but even at that distance, the air was misted with a fine salt spray which formed little pools on the swans’ feathers and trickled in tiny rivulets to the ground.

The most seaward pair of the Dragon’s Teeth, a double line of concrete tank-stops that had straddled the beach since the fear of invasion in 1939, were undermined by the waves and drawn down into the depths by the suction of the undertow. The deep rolling action of the waves disturbed the wrecks that lay off that treacherous coast, and pieces of jagged iron from landing craft and tramp steamers, together with waterlogged timbers from emigrant ships and Armada galleons were thrown up the beach and dragged down again, artefacts and treasures spilling across the seabed.

Further along the coast, the massive bulk of Portland stood firm against this storm as it had for ten thousand years and a thousand similar storms, protecting the deep waters of Weymouth Bay to the east.

Even so, the cliffs from White Nothe to Saint Alban’s Head were being pounded and eroded by the giant waves gnawing at their feet, bringing down cascades of chalky rock. Only at Lulworth Cove, where the narrow entrance excluded all but an occasional wave, was there calmer water. Here a few waves rolled in and exhausted themselves in the enclosed bay, the swoosh as each ran gently up the beach being drowned by the howling of the gale overhead.

The wind tore at the cliffs surrounding the cove, probing into every nook and cranny as though seeking out seabirds to toss through the air, but these birds, sensing an impending storm, had already flown inland.

Frustrated, the wind raced over the land, shaking and felling great oak trees and working loose the tiles and thatch on the cottages of the humans.

At the Tanglewood Knoll on the Great Heath, the wind found no new trees to topple. Another such storm some fifteen years before had felled all those that were not well rooted or were past their prime. The tangled trunks and branches on the ground below the standing pines gave the wood its name and protected it from the forays of gun-bearing humans.

In one of these pines, three elderly grey squirrels huddled together in a drey, feeling the wind rock the tree and expecting any minute that the drey itself would be blown out of the fork, and the twigs and mossy lining scattered over the wood. They feared that they too might be flung to the ground but each tried to hide his fears from the others.

Further to the east near the Blue Pool, now a wind-whipped mass of foam and bubbles, seven red squirrels had just had their drey torn to pieces around them. Shaken and breathless they were hurrying along the ground to seek shelter in a hollow tree, known to them as the Warren Ash. The wind fluffed up their tails and fur, and the stronger gusts bowled them over on the shifting, rustling mass of pine needles forming the forest floor.

Even further to the east, the wind picked up speed as it crossed the frothing waters of Poole Harbour to throw itself at the screen of trees that encircled the island of Brownsea – trees that surrounded and protected the meadows and the woodlands at the island’s centre. One violent gust caught a giant pine growing just behind the southern shore and snapped its trunk some six feet above the ground, the top bounding and rolling across the trackway behind, to lodge in the mass of romping rhododendron bushes.

This final act of vandalism seemed to satisfy the wind. As darkness fell, the force slackened and the stars, pricking through the blackness above the island, looked down on a ravaged landscape.

A moon later, in the mild spring sunshine Marguerite, a mature red squirrel, sat on top of The Wall. Not a wall – The Wall.

This brick-built structure was in the centre of Ourland, a beautiful island of woodland, meadows and heath set in the now placid waters of Poole Harbour. The Wall had once formed the back of a range of glass-houses which had provided grapes, peaches and other exotic fruit to the inhabitants of the Castle at the island’s eastern end. After many years of neglect, all that remained of the hot houses and the vegetable garden was The Wall.

It was about twice the height of a man and ran parallel to a track which had recently been cleared of undergrowth.

Marguerite had climbed the weathered brickwork, her claws finding holds in the crumbling mortar between the bricks. In these crevices moss grew, and from the top of The Wall, gossamer spiders’ webs reached out to nearby bushes.

She sat listening to the young squirrels playing at the other end of The Wall. From where she was she could not count them, but by the sound of their playful chatter there were ‘lots’. In fact she realised there were lots of young squirrels all over the island.

Now that the Scourge of Ourland, the pine marten, was dead, there were no predators to fear and the happy squirrels were following their Sun-inspired desires, mating and producing many healthy young dreylings. Something about all this had been making Marguerite feel slightly uneasy but she had not yet put a paw on the problem. She moved along the top of the wall to watch the game.

Having lived on the Mainland when she was a youngster, this island game was new to her. The rules seemed fairly simple. The young squirrels would scurry about on the ground while one climbed the wall and began a chant, at which all the others froze wherever they were. When the chant was complete, the squirrel on the wall selected a victim by calling their name and then tried to leap down on to him or her. No squirrel could move until a name had been called. If the leaping squirrel caught the named one, it would nip it with its teeth, but if it missed, the triumphant victim climbed the wall and took over as Leaper.

Marguerite watched for a while, listening to the chant with interest. It had the five, seven, five, sound pattern of a Kernel of Truth, yet the words did not make sense – perhaps she was mis-hearing them. Kernels should always make their meaning clear at once. There was even one which said –

A Kernel’s message

Should be wrapped in gossamer

Clever wraps obscure.

She moved closer, but her presence disturbed the youngsters, who held her in some awe. The game stopped, leaving the young squirrels sitting about uncomfortably. I’m sorry,’ Marguerite called down. ‘I didn’t want to spoil your fun. I was just trying to hear what you were saying. How does that chant go?’

The current ‘Leaper’ who she recognised as Dandelion’s youngest daughter, turned to her and replied,

‘I honour birch-bark,

The Island Screen. Flies stinging –

A piece of the sun.’

‘What does it mean?’ Marguerite asked, intrigued.

‘I don’t know,’ the youngster replied. ‘It’s what we always say – does it have to mean anything? It’s just a game.’