The Goddess Abides: A Novel (22 page)

There had been no time until now, not really any time: Arnold’s death; Edwin, his love and death; Jared and his love and hers, only in its beginning now that its path lay clearly before her. There had been no time. Now there was time, infinite time, until the very end of her life. She need not hurry herself. Now she knew that she, too, must search, quietly and firmly, for her own completion, for were she not complete, she could not take her place in Jared’s completion.

The organist was beginning to play the introductory music to marriage, tender music, the mood reverent and subdued. About her the people waited, their faces half smiling as they remembered, each his own remembering. The church was old-fashioned, very simple, almost a country church. Here June had been christened and by the very minister, then young, who was to perform the ceremony. He came in now, wearing his robes. In front of him walked two small boys, choristers, who carried lighted torches. When they reached the altar the small boys lit the candles on either side, and then took their places. The tender music drew to a close. A door to the side of the chancel opened and Jared came in with his best man, someone she did not know, a fellow scientist, he had told her, a brilliant boy of a man, he had said, working in space science. “He lives and breathes on a new level of existence,” Jared had said. “He makes the rest of us look earthbound and old hat.”

She remembered these words, but her eyes were on Jared. He looked abstracted, far away, almost unconcerned. How well she knew that look, how often her mother had complained of her father.

“Raymond! Do you hear a word I’m saying?”

Sometimes, half laughing, her mother said to those about her, “I don’t believe he even heard our marriage ceremony!”

Ah, June must learn to understand this divine abstraction, this cosmic absence! Once, she herself had inquired of a young wife whose young husband had traveled into space.

“Did he come back the same?”

“Not the same,” the young wife had said sadly. “Never quite the same.”

Ah, but June must be proud, not sad! And then, as though at the thought of June, the wedding march broke joyfully across the air. The audience rose and turned to watch the pretty procession, a little girl in a short pink frock walked down the aisle, scattering rose petals, behind her a tiny boy carrying a white satin ring cushion, and then, one after the other, three bridesmaids—young, all so young, all pretty in pink frocks. And at last June in bride’s white, the gleam of satin, the froth of lace, she walking beside her father, her white-gloved hand in his elbow, a tall graying man, still handsome, a famous man in the world, a great man in his way. But none would be greater than Jared. This was her lifework.

Then almost immediately it was over, the ceremony stripped to its essentials.

“I don’t want any nonsense,” Jared had said firmly.

There was no nonsense. The brief vows were said, be came down the aisle, head held high, and June clung to his arm, smiling bravely. A dart of compassion struck her heart. This young wife! It would not be easy to be Jared’s wife. She must think, too, of June, for June unhappy would be a burden Jared must not bear. And yet, she told herself, she must never interfere.

She laughed inside herself. Only a goddess could fulfill all that she was demanding of herself. This, then, was her first task, to make of herself a goddess, the first task and the most difficult. She must set herself apart if she was to fulfill the monumental task, which in itself must be perfection.

Someone, a young man, an usher, came to escort her down the aisle, and she walked to the door and out of the church to her waiting car. An hour’s solitary drive, and she was not lonely, an hour’s solitary drive and she was at the house again, and only when she entered the door did she remember there was a reception somewhere, at June’s home somewhere, a wedding cake to be cut, all of which she had forgotten, as abstracted in her own way as Jared in his, but she had her own dreams. Not to be fulfilled in this house, nor in any other in which she had ever lived! The knowledge came with the suddenness of conviction. She must build herself a house of her own, in the place which she had chosen so blindly, a place by the sea. The plans were where she had put them in a drawer in her desk. She had put them there months ago, not knowing whether she would ever finish them. Now she knew.

She took off her hat and tossed it to a chair. She went to the library, to her desk, and opened the drawer. The plans were there, as she had left them. She sat down and studied them. She could see the house as though it were already standing solitary on the cliff, overlooking the sea. The idea in itself was reality. As Edwin had said, the very idea of immortality made reality. Now the idea of the house, of herself, of Jared, were realities.

She heard a cough at the door. She looked up and saw Weston waiting.

“If you please, madame,” he said, “is there anyone here for dinner?”

“Only I—myself,” she said.

Pearl S. Buck (1892–1973) was a bestselling and Nobel Prize-winning author of fiction and nonfiction, celebrated by critics and readers alike for her groundbreaking depictions of rural life in China. Her renowned novel

The Good Earth

(1931) received the Pulitzer Prize and the William Dean Howells Medal. For her body of work, Buck was awarded the 1938 Nobel Prize in Literature—the first American woman to have won this honor.

Born in 1892 in Hillsboro, West Virginia, Buck spent much of the first forty years of her life in China. The daughter of Presbyterian missionaries based in Zhenjiang, she grew up speaking both English and the local Chinese dialect, and was sometimes referred to by her Chinese name, Sai Zhenzhju. Though she moved to the United States to attend Randolph-Macon Woman’s College, she returned to China afterwards to care for her ill mother. In 1917 she married her first husband, John Lossing Buck. The couple moved to a small town in Anhui Province, later relocating to Nanking, where they lived for thirteen years.

Buck began writing in the 1920s, and published her first novel,

East Wind: West Wind

in 1930. The next year she published her second book,

The Good Earth

, a multimillion-copy bestseller later made into a feature film. The book was the first of the Good Earth trilogy, followed by

Sons

(1933) and

A House Divided

(1935). These landmark works have been credited with arousing Western sympathies for China—and antagonism toward Japan—on the eve of World War II.

Buck published several other novels in the following years, including many that dealt with the Chinese Cultural Revolution and other aspects of the rapidly changing country. As an American who had been raised in China, and who had been affected by both the Boxer Rebellion and the 1927 Nanking Incident, she was welcomed as a sympathetic and knowledgeable voice of a culture that was much misunderstood in the West at the time. Her works did not treat China alone, however; she also set her stories in Korea (

Living Reed

), Burma (

The Promise

), and Japan (

The Big Wave

). Buck’s fiction explored the many differences between East and West, tradition and modernity, and frequently centered on the hardships of impoverished people during times of social upheaval.

In 1934 Buck left China for the United States in order to escape political instability and also to be near her daughter, Carol, who had been institutionalized in New Jersey with a rare and severe type of mental retardation. Buck divorced in 1935, and then married her publisher at the John Day Company, Richard Walsh. Their relationship is thought to have helped foster Buck’s volume of work, which was prodigious by any standard.

Buck also supported various humanitarian causes throughout her life. These included women’s and civil rights, as well as the treatment of the disabled. In 1950, she published a memoir,

The Child Who Never Grew

, about her life with Carol; this candid account helped break the social taboo on discussing learning disabilities. In response to the practices that rendered mixed-raced children unadoptable—in particular, orphans who had already been victimized by war—she founded Welcome House in 1949, the first international, interracial adoption agency in the United States. Pearl S. Buck International, the overseeing nonprofit organization, addresses children’s issues in Asia.

Buck died of lung cancer in Vermont in 1973. Though

The Good Earth

was a massive success in America, the Chinese government objected to Buck’s stark portrayal of the country’s rural poverty and, in 1972, banned Buck from returning to the country. Despite this, she is still greatly considered to have been “a friend of the Chinese people,” in the words of China’s first premier, Zhou Enlai. Her former house in Zhenjiang is now a museum in honor of her legacy.

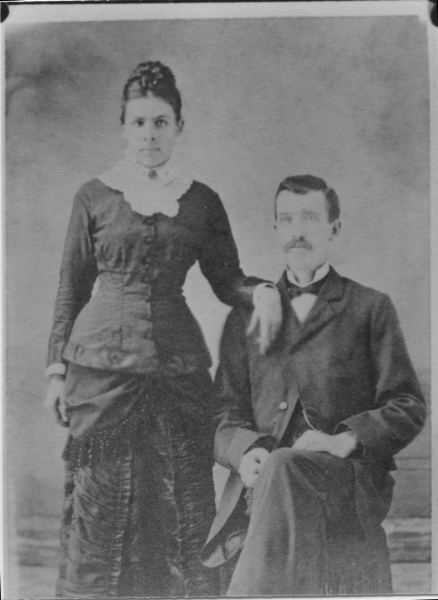

Buck’s parents, Caroline Stulting and Absalom Sydenstricker, were Southern Presbyterian missionaries.

Buck was born Pearl Comfort Sydenstricker in Hillsboro, West Virginia, on June 26, 1892. This was the family’s home when she was born, though her parents returned to China with the infant Pearl three months after her birth.

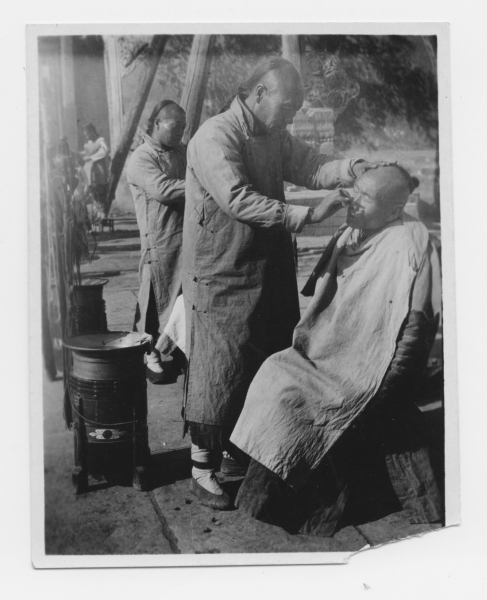

Buck lived in Zhenjiang, China, until 1911. This photograph was found in her archives with the following caption typed on the reverse: “One of the favorite locations for the street barber of China is a temple court or the open space just outside the gate. Here the swinging shop strung on a shoulder pole may be set up, and business briskly carried on. A shave costs five cents, and if you wish to have your queue combed and braided you will be out at least a dime. The implements, needless to say, are primitive. No safety razor has yet become popular in China. Old horseshoes and scrap iron form one of China’s significant importations, and these are melted up and made over into scissors and razors, and similar articles. Neither is sanitation a feature of a shave in China. But then, cleanliness is not a feature of anything in the ex-Celestial Empire.”

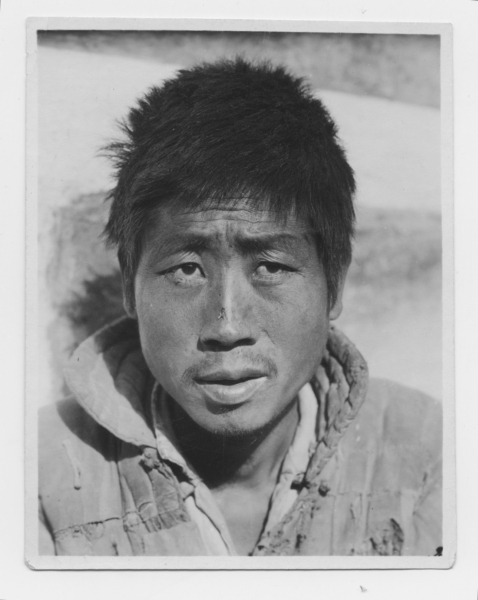

Buck’s writing was notable for its sensitivity to the rural farming class, which she came to know during her childhood in China. The following caption was found typed on the reverse of this photograph in Buck’s archive: “Chinese beggars are all ages of both sexes. They run after your rickshaw, clog your progress in front of every public place such as a temple or deserted palace or fair, and pester you for coppers with a beggar song—‘Do good, be merciful.’ It is the Chinese rather than the foreigners who support this vast horde of indigent people. The beggars have a guild and make it very unpleasant for the merchants. If a stipulated tax is not paid them by the merchant they infest his place and make business impossible. The only work beggars ever perform is marching in funeral and wedding processions. It is said that every family expects 1 or 2 of its children to contribute to support of family by begging.”