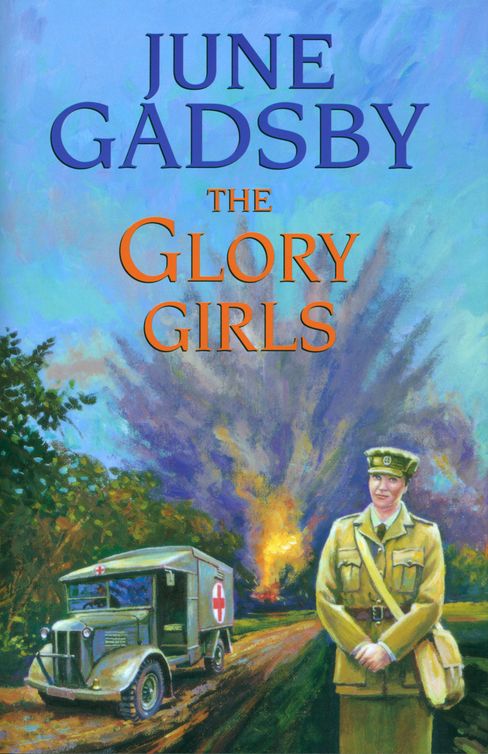

The Glory Girls

Authors: June Gadsby

June Gadsby

For the late Mary Lambert, a real heroine, and FANYs everywhere

With grateful thanks to the following for help with research: my husband, Brian Gadsby; Hugh Popham (The FANY in Peace & War); Pat Beauchamp (Fanny Goes to War); Sarah Helm (A Life in Secrets); Sir Winston Churchill (The Second World War) and the Casa Guilla, unique hotel of St Engracia, Lerida, Spain.

Any errors regarding the FANYs in this fictitious tale are uniquely my own.

T

HE

wind blowing across the land between the battlefield and the British Army Hospital camp carried with it echoes of bullets fired and exploding shells. The pretty white clouds on the horizon were not caused by weather changes, but were puffs of smoke arising above the battle sites. Frances Emily Croft imagined she could hear the cries of the soldiers falling to enemy bullets and bayonets. Or was it their tormented souls she could hear drifting over the mud-flats?

When she joined the First-Aid Nursing Yeomanry in 1913, searching for a worthy aim in life, she had not expected to end up like this. At first, it was so jolly with such good camaraderie and a vigorous and healthy life style. It left no room for regrets and fits of the miseries that so often attacked young women who wanted more out of life than simple domesticity. She loved the marching, the parades on horseback, the rigid routine of their lives in

training-camp.

And later, the feeling that one was doing something useful,

learning

to drive motorized ambulances, the exhilaration of taking an engine apart and knowing how to put it back together again in working order.

On the down side, perhaps, was the actual nursing element. It wasn’t too onerous learning how to roll bandages, clean and dress wounds – imaginary ones, of course. The trouble was she wasn’t good with people, so she had to learn how to be sympathetic too, rather than be impatient and irritable, which came far more naturally to her. No doubt, she had thought, she would muddle through, if she ever had to do it for real.

Reality came sooner than expected with the outbreak of war. Frances was among the first of the FANYs, as they were affectionately known, to be shipped out to the Flanders fields, where it was her unending task to

take supplies up to the trenches and transport sick and injured soldiers back to the hospital. The Belgian Tommies were very grateful for the service she and her fellow FANYs provided, but what they appreciated even more was the fact that these women, some of them mere girls, could communicate with them in their own language.

Now, the unit was in northern France. It had been a thrill to receive her posting here. The excitement was short-lived. When she saw the devastation of this much loved land she feared that it had been a wrong decision to commit herself so profoundly to the cause. Had she been a man – how happy her father would have been – it might have been the making of her. As it was, day after long day was wearing her down, and proving that she was not, after all, made of such stern stuff.

Frances gnawed on the end of a pencil stub and let out a long sigh. The wind suddenly changed, pummelling the canvas of the makeshift field hospital behind her. It whipped her hair out of its neat bun and bit into her tear-stained cheeks. There was a rattle of paper as the pages of her personal journal turned, going back like a time machine. She put out a hand to arrest their journey and the book fell open at a place she would rather not have revisited. However, the temptation to read again what she had written was too strong to resist. Strangely enough, it was like reading the account of a total stranger, in another life, another world.

How little I knew back then of life, she thought. How little I knew of me! I thought I was courageous and bold. Instead, I have found my

feminine

side. Why, I’m just a silly flibbertigibbet with a girl’s fragile heart, so easily broken. Whatever happened to brave, daring old Frances?

She scrubbed again at her smarting eyes and read the words before her, tracing them with a fingertip, not to miss a phrase or a nuance that would give a hint of the real Frances.

England, after so many years of living in France, is so cold, so drab, so boring. My prospects of marriage would appear to be nil – not that I’m the marrying kind; my prospects of an interesting life are even less. How lucky to find an organization such as the First-Aid Nursing Yeomanry. It is all thanks to the incredibly romantic dream of one man. A sergeant-major by the name of Edward Charles Baker, who served under Lord Kitchener. The idea, or it may have been a hallucination, came to him when he was wounded during the Sudan Campaign. At that time he thought that there was a missing link and that a troop of young women would do the job (How droll!). So here I am. One of Mr Baker’s ‘Missing Links’, and proud to be part of the

vision he had as long ago as 1907. I’m sure that every one of us is now more useful than we have ever been in ordinary life. One has to be a volunteer, of course, but what price that, set against the

excitement

of riding out into the fields of battle to bring aid and succour to the poor wounded soldiers? If there were any, that is.

The training is rigorous, carried out in camps around the country. We march, we train, we tone up our bodies, but most of all, we ready our minds for the fray. Whatever that means. However, it is more than a little exciting and the amicable rapport between the girls is incredible. We come from all walks of life, but mostly from the middle classes. There are, inevitably, one or two rather snooty

individuals

– they take some getting to know, but after a couple of weeks the ice is well and truly broken.

Being a good horsewoman is essential, of course. Not sure that I approve of the red tunic we are obliged to wear. It’s a little too gay for my quiet personality and too vivid for my rather drab

complexion

, but one cannot have everything.

Anyway, I have got this far and still have no inclination to

surrender

the flag. Goodness, what an adventure!

Frances turned the pages, her heart heavy with nostalgia for those early days, and for the hopes and ambitions she had carried with her.

By 1914, the diary entries became more erratic. One page stood out, alone and void of any description, but Frances experienced the same breathless squeezing of her heart as she had the day she had made the entry:

5 August, 1914: It seems that Britain is at war with Germany. Perhaps now we will see some real action. It will be FANYs to the fore from now on. I can’t wait.

31 October, 1914: Today we embarked for Belgium, heading for the battlefields with our trusty vehicles. My father’s beloved old Ford Model T has been drawn into the operation, converted into a small sitting ambulance or transport for generals, I suppose. He would be so proud to know that his car is to be used for saving lives. My poor father! I wonder what he would be doing now, had he not died so tragically of that silly heart attack? I’m sure they will never again have an Ambassador as loyal as he, not in the whole of France, or indeed in Europe. Mother, of course, thinks that I am totally absurd to continue with the FANYs in times of war. I cannot imagine why.

There is no way that I would want such a sedentary life as she enjoys. I have an overpowering need to ‘give’ and this silly little war will prove that I stand for something. Thank goodness they have done away with the red tunic. Khaki is so much more practical.

Frances started to close the journal, thinking to put it aside. It was late and she ought to get some rest before it was her turn to rush up to the trenches with a fresh supply of bandages, morphine, dry biscuits and tea. However, the wind seemed to have a say in things and mischievously turned the pages again, making them fall open this time to the less frequent entries during her time here in France.

The handwriting was erratic and unsteady, like that of an elderly person, and indeed, that was how she so often felt, so weary was she of the daily dose of danger and bloodshed. Days when there were just too many suppurating wounds to be drained and re-dressed, when morphine wasn’t enough to kill the pain, and she went to sleep with the screams of the patients in her ears.

The France I used to love so much is not the France that surrounds me now. I have swapped the idyllic countryside with its sleepy farms and flower-strewn meadows for trenches running with blood, disease and rotting flesh. I have to grit my teeth and hold on to the contents of my stomach. It would never do to show the other girls how weak I am, though Penelope Freeman fainted clean away at the sight of her first dead body, so I know I’m not alone.

Today I pulled up the sheets on three more of our dear boys in uniform, not one of them above the age of twenty. John, thank God, still holds on. It is our conversations, long into the night, that keep me going. We talk of golden dawns, birdsong and the love that one person has for another, imaginings of the future and our own dreams of a life without all this carnage.

I do not think of why I joined the FANYs. It is no longer worth a thought. Only in my weakest moments do I weep into my pillow and wish I were back in England – but it is only a fleeting wish and best buried among other impossible frivolities of my mind. My days are spent behind the wheel, taking out what first aid I can and

picking

up the injured, bringing them back here to the field hospital. We do what we can. It is never enough. But I have been able to spend time with my lovely sergeant. Long after the others are asleep and the guns and cannons are silent, I sit with him, holding his hand. It

seems right, somehow. I have never felt such love for any human being.

Something inside Frances’s heart twisted cruelly. She stuffed the

journal

into her knapsack, stood up and took a deep breath before returning to the dormitory where FANYs and registered nurses alike fell in and out of the low pallet beds, so exhausted that they did not worry about who had slept there before them. When the weather was wet and cold, as it often was, they were glad of the heat still lingering in the folds of the rough army blankets. Nobody cared any more about fleas or bedbugs. The greatest worry was trying not to contract dysentery or typhoid, which seemed to kill as many poor souls as did the German bullets.

Tonight, however, Frances was not ready for her bed. Sergeant John Temple was to be shipped out at first light in the morning. She had prayed for his recovery from his serious injuries, then she had prayed that he would not recover too quickly. Now, he was going to leave her and she did not know how she would cope without him, for they had enjoyed a very special relationship that she was sure she would never find with any other man.

‘Ah, dear sweet Fanny!’ John was the only person she had allowed to call her by that name. ‘You came!’

His face lit up at the sight of her as she walked between the beds of the surgical ward where he had hovered between life and death for so long.

‘How could I not come to see you?’ She smiled, feeling her lips quiver emotionally.

He reached out to her and they clasped hands as she sat down on his bunk beside him.

‘They say I’m going home tomorrow, Fanny,’ he told her, his kind and loving eyes searching her face. ‘I may not see you again.’

‘Please … John, don’t!’ Her throat was tight, the words strangled. ‘I can’t bear to think of being separated from you, but …’

He pulled her hands up to his face, kissing her fingers with light,

feathery

touches of his lips. She could see that he, too, was emotional, though she was sure that he would also be happy to get out of the war. Who would not be relieved to see an end to such horrors as these men had been forced to live through day after day, without pause?

‘Don’t forget me, Fanny, will you? And … and when this is all over….’

Frances nodded and felt tears sting her eyes. She did not cry often, but

today she had been unable to hold it back. She kissed his forehead tenderly, then briefly touched his lips.

‘We’ll find each other,’ she said in a croaking whisper. ‘I’ll wait for you, John, even if it takes for ever.’

‘Oh, Fanny, I do adore you!’ It was a heartfelt cry and then they were clinging together.

If they thought of a future together, neither of them spoke the words, yet there was a wealth of feeling in the silence they maintained.

By tomorrow he would be gone. Tomorrow she would be driving again to the trenches in her ambulance without a windscreen for cover, the wind and rain blinding her. There would be other soldiers needing her help. It would be hard, but the thought of going home, one day, to John, would be all she needed to keep her going.