The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763-1789 (96 page)

Read The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763-1789 Online

Authors: Robert Middlekauff

Tags: #History, #Military, #United States, #Colonial Period (1600-1775), #Americas (North; Central; South; West Indies)

While this plotting was getting under way, Sir William Howe demanded a Parliamentary inquiry into his conduct in America. Howe stated to Parliament "that imputations had been thrown on himself,

____________________

4 | For differing accounts of the episodes discussed in this paragraph and the next, see Herbert Butterfield, George III, |

and his brother, for not terminating the American war last campaign" and asked for an inquiry into "whether the fault lay in the commanders of his Majesty's fleets and armies, or in the ministries of state."

5

He then paraded witnesses before the Commons, including Lord Cornwallis and Major General Charles Grey, to substantiate his contention that fault lay with the ministry and not with himself or his brother.

Cornwallis, who said that he would confine himself to the facts and keep his opinions to himself, gave a version of the "facts" that rather subtly tarnished Howe's self-portrait as the aggressive commander in America. Grey turned out to be a much better witness, describing difficulties that would have thwarted any military chief this side of Julius Caesar. The American countryside was so rugged, Grey testified, as to make reconnoitering it almost impossible. Against an enemy determined to fight a defensive war, reconnaissance was essential, but in a country made for the defensive and inhabited by a distinctly unfriendly people, attack was difficult to prosecute.

Germain now proved his inner toughness. The implications of Grey's report were clear and easily drawn, but Germain was not about to concede that Howe required further support from home to win the war. Rather he trotted out Major General James Robertson, who proceeded to give a version of things that made Howe's failure inexplicable except in terms of his own incapacity and disinclination to fight. In Robertson's account the Americans appeared as overwhelmingly loyal to the king -- in his solemn statement two-thirds of them favored the king's government and the Declaration of independence, far from representing popular opinion, emanated from "a few artful folks" who not surprisingly rejoiced in it by themselves. As for the countryside, it abounded in food supplies and a people eager to give information about the traitorous forces under George Washington. Moreover these people would fight for their king; they wanted nothing so much as a good chance, and capable leaders, to help them escape "Congress's tyranny."

6

This testimony seemed damning, but the Howes struck back. Their blows were returned, and the inquiry dragged on until the end of June. And when it ended in Parliament, it was resumed in the press -- to no one's satisfaction.

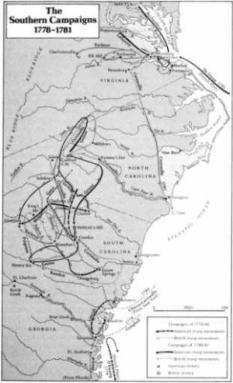

Meanwhile, the ministry and General Clinton, in America, agreed on a strike against Charleston, South Carolina.

What could not be settled

____________________

5 | John Almon, ed., |

6 | Ibid., |

in Parliament might be played out in America. The place for a new beginning lay in the southern colonies.

The expedition left New York's harbor with difficulty on December 26, 1779. Loading the transports had called on all the skill of the sailors manning the small boats ferrying the troops and supplies. Temperatures had been low for several weeks, ice clogged the harbor, and winds made handling the boats a treacherous business. The 33rd Regiment, which was Cornwallis's, set out one day only to be forced back to the wharf. 7

Clinton, always a poor sailor, who hated the sea even when it was untroubled, must have been relieved when the ships -- some ninety transports and fourteen warships -- departed the harbor in relatively good weather. During the night of December 28-29, whatever he was feeling was doubtless replaced by seasickness as a heavy storm heaved the ships about. Although over the next four weeks the winds occasionally abated and the seas flattened, a series of storms blew the fleet apart.

By January 6, 1780, Johann Hinrichs of the Jaeger Corps, who kept a careful diary of the voyage, was writing: "Always the same weather!" The "same" was "Storm, rain, hail, snow, and the waves breaking over the cabin, such was today's observation." During the worst of it, the ships,would furl their sails and drift during the night, with the wheel lashed down and the ship buttoned up as tightly as possible. In the mornings, when they could see, each ship would discover that it was alone, or in the company of only a few others. During the day that followed the ships would attempt to collect themselves if the weather permitted. Usually the weather permitted little, as masts crashed down under the pounding, sails were ripped to shreds, and hulls sprang leaks. Captain Hinrichs watched the sinking of the George, a transport with the infantry aboard "throwing their belongings and themselves head over heels into the boats." The soldiers fared better than the horses, most of which were injured and had to be destroyed. Stores of all sorts were also damaged, and much was lost as ships went down. 8

At the end of January the transports and their escorts began to drift into the mouth of the Savannah River, to Tybee Island, where the crews dried out and repaired their vessels. They were of course far south

____________________

7 Willcox, Portrait of a General, 301.

8 Johann Hinrichs, Journal, in Bernhard A. Uhlendorf, ed., The Siege of Charleston (Ann Arbor, Mich., 1938), 121, 127.

of their destination, which originally was the North Edisto Inlet about thirty miles from Charleston. Within ten days Clinton declared the army ready to proceed, and on February 11 the troops began putting ashore on Simmons Island (now Seabrook) on the Edisto Inlet. This move occasioned a different sort of heavy weather between Clinton and Vice Admiral Marriot Arbuthnot, the naval commander who had followed Sir George Collier and who was Clinton's equal in rank. Clinton had liked Commodore Collier, and the two had worked well together. Marriot Arbuthnot proved to be much more difficult to work with. He was sixty-eight and did not exude energy. He was not without experience, but he had not commanded either a major station such as the North American waters nor had he taken part in a large venture with the army. He was unpredictable, sometimes determined, sometimes indecisive. He was given to bursts of both confidence and fears, and the bursts proved impossible to anticipate, let alone explain. He did not relish the responsibilities of his new command -- nor should he have, for he lacked a strategic sense and the skills of a great sailor. He was, in short, just the sort of companion Clinton did not need. The two men disagreed on where the troops should go ashore, a disagreement that would be followed by others more serious. Clinton urged that the landing should be at the North Edisto Inlet, apparently because the voyage there would be a day or two shorter than to the Stono Inlet, the place Arbuthnot proposed. In the argument that followed, Clinton invoked the authority of one of Arbuthnot's skippers, Captain Elphinstone, who knew the waters around Charleston better than anyone else on the expedition. Arbuthnot gave way, but apparently with little grace. And in the exchange between the two the outlines of a feud were etched. All the troops and much of their baggage cleared the ship three days after the landing began. Over the next ten days the army slogged its way across the marshes on Johns and James islands. Clinton then sat them down in a rough camp and, aside from establishing a beachhead at Stono Ferry on the mainland, stopped his advance. There were reasons for delay: the army needed to establish supply depots and magazines, and Clinton believed that it needed reinforcements. He promptly sent for the detachments in Georgia and ordered that troops be sent from New York. ____________________

|

wagons over the soggy ground, proceeded slowly in building up the magazines. Clinton also had to wait on the navy to make its way into the upper harbor, where its heavy guns could be put ashore for the siege he had decided upon and where its small boats could be used to ferry troops across the Ashley River to the peninsula on which Charleston was located.

10

Charleston, the only city of any size in the southern states, ordinarily numbered 12,000 citizens, mostly of English stock but with sizable numbers of black slaves, French Protestants, and a sprinkling of Spaniards and Germans. It lay on a peninsula cut by the Ashley River on the west and the Cooper on the east. Visitors found it beautiful and, though hot in summer, cooler than the inland areas. Wealthy rice planters aspired to houses in the city, and many built them in order to escape the worst of the summer heat. Altogether there were some eight hundred, or perhaps a thousand, houses sitting along broad streets which intersected one another at right angles. Most of the houses were of wood and rather small -- at least by European standards. Along the two rivers, though, handsome and large brick houses had been built, and many owners had put in gardens behind them.

11

Since 1776, Charleston's defenses had decayed. From the seaward side, the side that had thwarted Parker and Clinton in 1776, Fort Moultrie on Sullivan's Island on the east and Fort Johnson on the west had fallen into disrepair. They were occupied, however, and seemed to stand in the way of an enemy coming through the outer (or lower) harbor. In reality, nature offered a more formidable obstacle in the shape of a heavy sand bar. The bar could be crossed at five places, but at all these points the water was so shallow as to prevent the passage of heavy ships. Frigates and smaller vessels could make it, but not without lightening themselves. A series of terraced works of palmetto logs protected the tip of the Neck, as the peninsula was called, and along the side of each river there were redoubts, trenches, and small fortifications. The redoubt at the tip held sixteen heavy guns, and the forts along the river had from three to nine guns each. There was a small flotilla of ships in the upper harbor under Commodore Whipple when the siege began, but they were scuttled at the mouth of the Cooper when Arbuthnot crossed the bar on March 20.

Their guns and crews were sent ashore

____________________

10 | William T. Bulgar, ed., "Sir Henry Clinton's 'Journal of the Siege of Charleston, 1780",' |

11 | There is a fine contemporary description of Charleston in the "Diary of Captain Ewald", Uhlendorf, ed., |