The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763-1789 (78 page)

Read The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763-1789 Online

Authors: Robert Middlekauff

Tags: #History, #Military, #United States, #Colonial Period (1600-1775), #Americas (North; Central; South; West Indies)

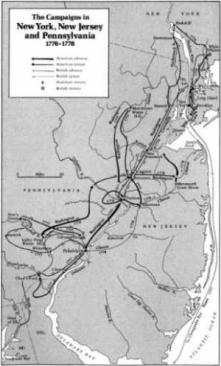

As engrossing as these problems were, Howe relieved Washington's mind of them at least temporarily on October 12, when he broke the early autumn quiet by putting 4000 men ashore on Throg's Neck. The neck, variously called Frog's Neck or Frog's Point, was sometimes a peninsula and sometimes an island, depending upon tide action and fresh-water drainage, and extended into Long Island Sound almost due east of the American lines. The Royal Navy carried the soldiers through Hell Gate in the fog; their landing was unopposed. But getting off Throg's Neck was no easy matter because American detachments guarded the exits -- several fords and a small causeway over a creek.

27

Although Howe seemed bottled up, he had outflanked the American army on Harlem Heights. Four days later Washington decided to move north to White Plains, a day-long march, and on October 18 he began pulling his forces off the Heights. Because of the shortage of horses and wagons this movement occupied four days, with the troops themselves pulling the artillery. Howe accommodatingly left the Americans unmolested, though on the day they began their move he embarked his force once more and landed farther up the Sound on Pell's Point. A small American brigade under Colonel John Glover gave the Hessian

____________________

26 | Freeman, |

27 | Ward, I, 254-56. |

advance party a short fight, but Howe's men soon took the Point without difficulty.

The British did not make their way to White Plains for another ten days, where on October 28 they assaulted and captured Chatterton's Hill on the extreme right of the American lines. Three days later Washington pulled his army back to North Castle and a new line of entrenchments. Howe followed as far as the old lines, but during the night of November 4 he withdrew -- Washington erroneously called the move a "retreat" -- and ten days later Howe was in position around Fort Washington on the east side of the Hudson below Kingsbridge.

28

During these ten days Washington speculated on Howe's intentions and prepared to pull a part of his army out of North Castle for service in New Jersey. There did not seem to be much doubt that Howe would attempt to capture Fort Washington, but that would not satisfy him. In studying Howe's behavior, Washington projected one of his own values into Howe's mind -- a concern for reputation. Washington was always affected by what others thought of him. That he believed that the enemy was moved by a similar concern was clear in a rhetorical question he asked about Howe: "He must attempt something on Account of his Reputation, for what has he done yet, with his great Army?" Howe's immediate objective seemed obvious: to invest Fort Washington, but, if he succeeded, what next? Perhaps he would move to the southern colonies, and perhaps he would drive through New Jersey for Philadelphia, where the Congress held forth. For the moment, Fort Washington seemed to be the obvious objective. "Could the Americans hold it?" was a question soon translated into another: Was holding it necessary or worthwhile after British warships forced their way through the obstructions in the Hudson between Fort Washington and Fort Lee on the west bank? The American guns in these forts had fired on the warships making their way up the Hudson but with little effect beyond minor damage to rigging and sails.

29

As soon as the British proved that the two forts could not stop their ships, Washington began to think of evacuating Fort Washington. It seemed prudent not to risk the 3000 troops there, especially since Howe's force outnumbered them three or four to one. But Washington was not on the scene, and the commander of the area, Nathanael Greene, and his subordinate, Colonel Robert Magaw, who led the garrison inside the fort, believed they could hold out.

Washington expressed his doubts

____________________

28 | GW Writings |

29 | GW Writings |

to Greene in a letter written on November 8, 1776, but hung back from giving a direct order. He did not wish "to hazard the men and Stores at Mount Washington, but as you are on the Spot, leave it to you to give such Orders as to evacuating Mount Washington as you Judge best and so far revoking the Order given Colonel Magaw to defend it to the last."

30

Being on the scene or "on the Spot" described a most desirable condition in Washington's mind. He was not a commander who trusted abstractions, nor did he ever wish to make decisions at a distance. He wanted to see things for himself and did so: at Cambridge, he reconnoitered the lines and inspected camps; on Long Island he did not order a withdrawal until he could supervise it himself; he raced to Kip's Bay to see the disaster with his own eyes; and he got as near the battle of Harlem Heights as he prudently could. He had the imagination to be a map general but not the inclination. He could hold a representation of troop dispositions and a battlefield in his head, but he preferred to be on the spot. One of the skills he acquired as a young man was the art of surveying, an art that required its practitioners to pace the ground. He was a planter and a land speculator, with a feel for the earth, for terrain. Though he could reason from a distance, he wanted the evidence his senses provided before bringing his judgment to bear.

Washington did not arrive on the scene until just before the British moved on Fort Washington, and when he got there he found Nathanael Greene, an attractive, confident personality and an able and articulate man who said the place could be defended. Of course Greene had not fought a major battle -- he won his spurs as a tactician after this disaster -but he was obviously bright and he was self-assured, and presumably he had earned the right to predict from being on the ground.

31

Greene had the right to make a prediction, but there was no good reason to trust him. Washington, however, did trust him -- in defiance of his own instincts, whose promptings were confirmed by a visual inspection on November 14. At the decisive moment, a strong, steady personality allowed itself to be swayed by the enthusiasm of a more youthful, exuberant, and optimistic one.

On November 16, Howe destroyed Greene's illusions and confirmed Washington's fears.

The British moved into position the day before

____________________

30 | Ibid., |

31 | On Greene's responsibility for the loss of the fort, see Richard K. Showman et al., eds., |

around the American lines. These lines, about five miles on a side, were much too far from the fort itself, which consisted of breastworks on the Heights of Washington, 230 feet above the Hudson. Howe demanded the surrender of the fort, and Magaw refused in a grand response which soon sounded absurd: "Give me leave to assure his Excellency that activated by the most glorious cause that mankind ever fought in, I am determined to defend this post to the last extremity."

32

The next day General Percy struck Lt. Colonel Lambert Cadwalader's Pennsylvanians from the south, General Edward Mathews, Cornwallis in reserve, pressed against Colonel Baxter's militia from the east, and General Wilhelm von Knyphausen drove against Lt. Colonel Moses Rawlings's Maryland and Virginia regiments. Knyphausen's Hessians took heavy losses from the Marylanders and the Virginians, but in three hours the lines on all three sides had collapsed. Compressed into the fort, disorganized, and near panic, the Americans could not have held out long. They did not offer more resistance, and Magaw surrendered them that afternoon. British dead were numerous -- almost 300 -- but the total American casualties were far heavier -- 54 killed, 100 wounded, and 2858 captured. Valuable stores, artillery, and ammunition were also taken.

33

Four days later, on the morning of November 20, Cornwallis took 4000 regulars across the Hudson, landing at Closter, New Jersey, about six miles above Fort Lee. His objective was the American army in New Jersey, which was divided between Hackensack and Fort Lee. Washington had taken 2000 men across the Hudson at Peekskill on November 9 and 10, leaving General Heath at Peekskill with around 3200 troops guarding the approaches to southern New England; Charles Lee and 5500 men remained at North Castle. To complete the sweep of the Hudson River forts, Cornwallis marched quickly to the south and almost trapped the garrison at Fort Lee. Failing to squeeze Greene and Washington between the Hackensack and Hudson rivers, he delayed pursuit for another week.

34

Washington and a disorganized and dispirited force of 3000 marched and straggled from Hackensack on November 21. They made it to Newark the next day and rested for the following five days. Late that week Cornwallis set his troops in motion; his advance party reached the town

____________________

32 | Quoted in Theodore Thayer, |

33 | Ward, I, 267-74. For casualties, Peckham, |

34 | Ward, I, 276-77; |

on November 28 just as Washington's rear guard cleared out. The Americans reached New Brunswick on November 29, and a day later bade farewell to 2000 militiamen from New Jersey and Maryland whose enlistments expired. These men had stood all they cared to; they were going home. Cornwallis was in full pursuit now and moving as fast as he could over muddy roads, his pace slowed somewhat by rain and cold weather. He almost caught Washington a second time, at New Brunswick, December 1, but was stopped there by Howe's order. Washington's men had chopped down the timbers supporting the bridge over the Raritan in any case. Still, Cornwallis was criticized at the time, and ever since, for not pushing on, though his men were exhausted and he had his orders.

35

Washington's command reached Trenton on the Delaware River on December 3; Howe, who had joined Cornwallis at New Brunswick, resumed the pursuit three days later and almost caught the Americans at Princeton on the 7th. The next day at midmorning the British moved out. Men they got to Trenton, they found the river full of water and empty of boats. Washington had crossed, taking them all with him and ordering all that could be found up and down the river destroyed or floated to the west bank.

36