The Glimmer Palace (39 page)

Read The Glimmer Palace Online

Authors: Beatrice Colin

Tags: #Fiction, #Literary, #Historical, #War & Military

“I met a man,” Hanne said as soon as Lilly sat down. “He is an art dealer. He said he’d been coming to the cinema for weeks on the off chance of seeing me. And I never even knew.”

Her eyes were large and black and she could not stop smiling. At the next table a man laughed long and loud. Although it was only nine in the morning, at the bar a drunk started to sing.

“He wants to marry me,” Hanne whispered for full effect. “When he has divorced his wife. And then we’re going to live in his house in the Grunewald with a huge garden.”

Lilly poured a cup of tea from the pot already cooling on the table.

“So he’s married already?”

“What? Oh, yes,” admitted Hanne. “He married young, forced into it by his parents. It was a mistake.”

“Does he have any children?”

Hanne exhaled loudly. “He has two young daughters. Of course, I said they could come and stay with us anytime . . . and who knows, I might, you know . . .”

Lilly picked up the milk jug. It was empty. She turned to look for the waiter. Hanne’s mouth began to twist.

“How can you be so disapproving? Isn’t this what you wanted? To get me off your hands?”

“I’ve never thought that, Hanne.”

Lilly took a sip of lukewarm black tea.

“What’s his name?” she asked.

Hanne paused as if weighing up whether to trust her.

“Edvard.”

Lilly looked at Hanne and they both started to laugh.

“It’s not funny,” said Hanne. “His mother was English. He has perfect manners.You won’t believe it.”

Hanne and Edvard invited her to an engagement party in September. The invitation arrived at the studio. It was addressed to Miss Lidi and partner. Ilya was editing the Arabian film, so Lilly went alone. Edvard welcomed her with both arms. He was a lugubrious man almost twenty years older than Hanne, with sad, baggy brown eyes, a head of thick white hair, a bushy mustache, and short, fat fingers.

“At least he has all ten of them,” Hanne whispered when she noticed Lilly’s eyes focus on his hands. “And he has more money than he knows what to do with.”

As Hanne led her by the hand to the drinks table, Lilly noticed that the room was full of artists and fellow dealers, writers and editors. She was Hanne’s only guest.

“You’re my only respectable friend,” Hanne whispered.

The wife had insisted that the ownership of the house in Grunewald be transferred to her, so the betrothed had moved into the former family home, a large rented apartment in the west of the city. It had, as Hanne boasted later that night, a telephone in the bedroom and a shower with a head the size of a dinner plate.While most households had lost their servants to the war effort and had never reinstalled them, Edvard still retained a housemaid, a cook, and a driver. However, the cook had taken one look at Hanne and resigned on the spot.

Cinema, Edvard was fond of saying, was his undoing. From the first film he ever watched—Harry Piel in

Under a Hot Sun

, in a tent somewhere in France in 1916—to the films of Chaplin, Harold Lloyd, and Werner Krauss, the big screen rapidly replaced painting as his primary passion. While he was once moved by a well-placed brushstroke or a particularly vibrant shade of vermilion, he soon came to regard two-dimensional representation as nothing more than room decoration for the wealthy. Instead, he willingly succumbed to tales of cunning criminals, hapless heroes, and tragedies overcome just in time to finish with bright, trashy happy endings, twice during the week and four times at the weekend.

The first time he saw Hanne Schmidt, standing with her electric torch and ticket punch, he did a double take. He knew he had seen her before but couldn’t place her. In fact, he had watched her “acting” three times over one hot day in July 1918, when his wife and children were in the country. In the murky humidity of a Saturday matinee, at first she thought he was asking her directions to the men’s conveniences. But then she realized he was not saying “Do I have to go outside?”but “Will you go out with me?” By this time she was nodding fervently, which he took to mean yes even though she probably would have said no if she had heard him correctly.

He was waiting for her at the main doors at the end of her shift. He took her to the Romanisches Café opposite the Memorial Church. It was open all night, every night, and this night, like any other, it was jam-packed.They were shown to a table, a table that was permanently reserved for him alone, then he ordered a bottle of kümmel and chose a cigar from a box. And as the chess players silently battled upstairs on the balcony and the painters argued loudly at the bar, she looked at him and believed, for that moment at least, that he was just what she was looking for after all. month after they met, Rathenau was assassinated. The foreign

minister and millionaire industrialist was gunned down as he drove to work in his open-topped car. The reason suggested was that he was part of a Jewish conspiracy.

There had already been three hundred seventy-six political assassinations since the war. Most of the victims were liberals; almost half were Jewish. More than three hundred fifty murders were carried out by right-wing groups; around twenty by the left. The average prison sentence for left-wingers, however, was fifteen years; the average for the right wing, four months.

And yet workers left their factories and took to the streets of every city in Germany to protest Rathenau’s murder. The labor unions declared a day of mourning. His body was laid in state in the Reichstag. Over a million mourners were recorded on the streets of Berlin, several million more in Hamburg and Frankfurt. It was an outrage, everyone agreed, a travesty, a crime of cowardice and misguided prejudice. Two of the assassins were tracked down; one was shot, the other shot himself. Thirteen years later, however, Himmler laid a wreath on their graves.

Although his mother claimed to have English roots, Edvard was a German of Jewish descent on his father’s side. Like Rathenau, he had fought in the war and been decorated. He was, however, heartened by the public’s collective outrage.

“You see,” he told Hanne. “It is a random act by schoolboy fanatics. Everyone knows that there is no such thing as a Jewish conspiracy. Germany is the Fatherland. I feel perfectly safe here.”

And, sitting in his drawing room, where decorative paintings and Venetian-glass mirrors still covered every wall—where the heavy oak furniture looked as if it had been there since the beginning of time and the clock ticked the smooth, peaceful hours away—it was impossible to imagine that in one short decade, all of it would be gone and that, only a few years after that, Edvard would be dead from a hole he himself had fired into the soft, cultured recesses of his very large brain. It was impossible to imagine. But it would happen.

Berlin was swarming with foreigners; Americans, French, Swiss, and Dutch businessmen all bought up flats by the block or occasionally by the whole street. They opened hotels, started literary magazines, and bought paintings. Some relocated from New York and Boston just to live cheaply and luxuriously on black-market caviar and crateloads of gin.

In October, Mussolini marched into Rome with thirty thousand Blackshirts and was handed power by King Victor Emmanuel III. In Munich, Adolf Hitler, the man who had taken over the leadership of the NSDAP and renamed it the Nazi Party, watched and was inspired. Gone were the endless committee meetings, and instead a single strong leader, Der Führer, now led the party. The party newspaper,

Völkischer Beobachter

, increased its production to twice a week and would eventually be published daily. Membership grew from six thousand to thirty-five thousand in under a year.

In late 1922, when a shipment of telegraph poles failed to arrive in France, French and Belgian troops invaded the Ruhr Valley and took over the steel factories, the coal mines, and the railways. To retaliate, the Weimar government ordered the workers to go on strike. Nothing was produced or ran in or out of the valley for months, and 150,000 people were forced out of their homes by the invading armies. The government started to print money to pay wages and cover living costs. Businesses were also allowed to print their own banknotes, and soon railways, factories, even pubs, were producing money. It was, however, soon worth less than it cost to print. One day a cup of coffee in a café might cost five thousand marks. An hour later it would have risen to eight thousand.You soon needed a suitcase of money to buy a sausage. At one point a dollar was worth over four billion marks.

In a matter of months, wealth that had taken centuries to accumulate became worthless. A former bank manager withdrew all his savings, used it to buy a U-Bahn ticket, and traveled round the city once before returning home to starve to death. A family of four who were used to dining at their mahogany table on beef stew and apple cake burned the table to keep warm and then drowned themselves in a lake. A local director borrowed money from a currency speculator and bought his own theater.The show sold out every night but he still ended up with debts that would take several lifetimes of hard labor to repay.

But the film industry managed to weather the inflation. New cinemas were opening daily, and for the starving, the homeless, and the cold they were still a place of escapism, of refuge, of warmth.

ne morning, a letter with a Russian stamp arrived in Ilya Yurasov’s mailbox. It had come via the consulate. He looked at it for several minutes before he opened it.

My dearest Ilya,

wrote Katya Nadezhda.

I am living in the Crimea but now I am alone. Since my last letter, my life has been intolerable in so many ways.We left with nothing but the clothes we were wearing. My darling daughter succumbed to typhus a few months ago. So much sadness. So much torment. But how I long to see you again, my dearest Ilya. I have your photograph in front of me as I write. You are all I have now. All sailings to the West have now been suspended but I have heard that it is still possible to escape through Poland. I know we will meet again soon. Wait for me.

Until then,

your beloved, Katya

The date, written in the top right-hand corner, was May 1920. It had taken more than two years to reach him.

Kinetic

I

na runs out from work two or three times a day to buy things, some-things, anythings: shoes that don’t fit, a couple of glass eyes, a pipe, or a pound or two of salt. Someone will want them someday, surely?

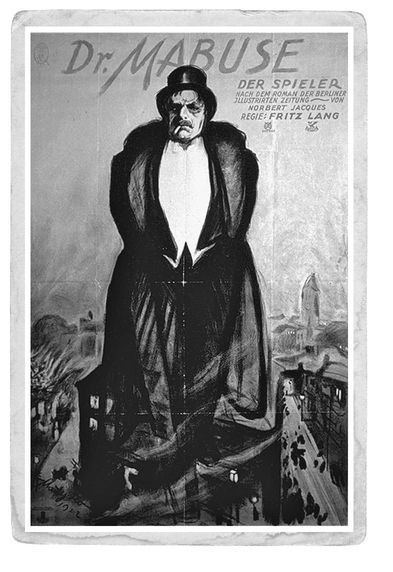

Tonight she has a date with a man she met in a queue.They meet at the cinema to see

Dr. Mabuse,

his choice, not hers. The curtains part and the show begins. Dr. Mabuse hypnotizes his victims. Dr. Mabuse is an evil tyrant, a megalomaniac, a cunning impersonator. Dr. Mabuse has gone mad in his basement workshop; his face is a white dot in a black background.Then, all of a sudden, that face rushes forward and fills the screen. Ina screams. She grabs the man’s hand. It is damp and clammy. She instantly lets it go again.

“Don’t you like me?” the man says later.

A deal is a deal. He paid for the tickets; she should let him kiss her. A tram is approaching. He lunges, his face is in her face, as big as Dr. Mabuse’s.The doors open, he grabs at her; he won’t let go. Ina jumps onboard as the tram starts to move off, and watches him recede, smaller and smaller, still holding her handbag with nothing inside but a lipstick, two glass eyes, and a bag of salt.

By the end of 1922, Lidi had made nine films. All of them were directed by Ilya Yurasov. She filmed on location at the brand-new amusement park and the Berlin Winter Palace. She had also filmed on sets dressed to look like nineteenth-century Paris with flats of Sacré-Coeur and Notre Dame, deep, dark forests with cardboard rocks and fake snow, and claustrophobic interiors where staircases led nowhere and the walls leaned in at strange angles.

She had played a bank teller, a coquette, a trapeze artist, and a serving girl; she had taken her own life twice, once by drowning herself in a river and once by taking poison, and killed her wayward lover three times. She had been both the object of desire and the objectifier, the betrayer and the betrayed, the lover and the beloved. It soon became obvious that there was something about Lidi’s manner that gave gravitas to even the flimsiest of plots.

“She is a pioneer,” Mr. Leyer was fond of saying.

Mr. Leyer would later argue that cinema was as important in the development of interhuman communication as the printing press. From the moment the lights lower and we begin to watch a drama unfold, we observe, in huge close-up, the faces, the reactions, the emotions of our chosen heroes and heroines. Of course, these people are only actors and they are directed to provoke a given response, but this passive observation could be regarded as something that would fundamentally change the way we perceive ourselves and the way we relate to others. As Horace M. Kallen pointed out in 1942, “Slight actions, such as the incidental play of the fingers, the opening or clenching of a hand . . . became the visible hieroglyphs of the unseen dynamics of human relations.”

In other words, a character’s interior life could be revealed in a way it had never been revealed before; the gibberish of human emotion could be translated, transcribed, embellished; the potential of any given situation could be tested, played out, concluded, without any real emotional cost. It was as if, Mr. Leyer would note, we had accidentally stumbled on the medium of our dreams.