The Giza Power Plant (23 page)

Chapter Nine

THE MIGHTY CRYSTAL

K

nowing that we can design an object to respond sympathetically

with the Earth's vibration, how do we utilize that energy? How can we turn it into usable electricity? We must, first of all, understand what a transducer is. Earlier on we discussed the piezoelectric effect vibration has on quartz crystal (refer to Figure in chapter eight). Alternately compressing and releasing the quartz produces electricity. Microphones and other modern electronic devices work on this principle. Speak into a microphone and the sound of your voice (mechanical vibration) is converted into electrical impulses. The reverse happens with a speaker, where electrical impulses are converted into mechanical vibrations. As I mentioned, it also has been speculated that quartz-bearing rock creates the phenomenon known as ball lightning. It can do so because the quartz crystal serves as a transducerâit transforms one form of energy into another. When we understand the source of the energy and have the means to tap into it, all we need to do to convert the unlimited mechanical stresses therein into usable electricity is to utilize quartz crystals! As you might guess, the Great Pyramid contains quartz crystals, its own transducers.

Let me make no apology for the theory I am proposing. The Great Pyramid was a geomechanical power plant that responded sympathetically with the Earth's vibrations and converted that energy into electricity. They used the electricity to power their civilization, which included machine tools with which they shaped hard, igneous rock.

OK, you may say. Prove it! Just how does this power plant work? Well, let us start with the power crystals, or transducers. It so happens that the transducers for this power plant are an integral part of its construction and were designed to resonate in harmony with the pyramid itself and also with

the Earth. The King's Chamber, in which a procession of visitors have noted unusual energetic effects and in which Tom Danley detected infrasonic vibrations (which I postulated were coming from the Earth) is, in itself, a mighty transducer.

In any machine there are devices that function to make the machine work. This machine was no different. Although the inner chambers and passages of the Great Pyramid seem to be devoid of what we would consider to be mechanical or electrical devices, there are devices still housed there that are similar in nature to mechanical devices created today. These devices also could be considered to be electrical devices in that they have the ability to convert or transduce mechanical energy into electrical energy. We might think of other examples, as the evidence becomes more apparent. The devices, which have resided inside the Great Pyramid since it was built, have not been recognized for what they truly were. Nevertheless, they were an integral part of this machine's function.

The granite out of which the King's Chamber is constructed is an igneous rock containing silicon-quartz crystals. This particular granite, which was brought from the Aswan quarries, contains fifty-five percent or more quartz crystal. Dee Jay Nelson and David H. Coville saw special significance in the builders' choice of granite for constructing the King's Chamber. They wrote:

This means that lining the King's Chamber, for instance, are literally hundreds of tons of microscopic quartz particles. The particles are hexagonal, by-pyramidal or rhombohedral in shape. Rhomboid crystals are six-sided prisms with quadrangle sides that present a parallelogram on any of the six facets. This guarantees that embedded within the granite rock is a high percentage of quartz fragments whose surfaces, by the law of natural averages, are parallel on the upper and lower sides. Additionally, any slight plasticity of the granite aggregate would allow a ''piezotension'' upon these parallel surfaces and cause an electromotive flow. The great mass of stone above the pyramid chambers presses downward by gravitational force upon the granite walls thereby converting them into perpetual electric generators.

The inner chambers of the Great Pyramid have been generating

electrical energy since their construction 46 centuries ago. A man within the King's Chamber would thus come within a weak but definite induction

field.

1

While Nelson and Coville have made an interesting observation and speculation regarding the granite inside the pyramid, I am not sure that they are correct in stating that the pressure of thousands of tons of masonry would create an electromotive flow in the granite. The pressure on the quartz would need to be alternatively pressed and released in order for electricity to flow. The pressure they are describing would be static and, while it would undoubtedly squeeze the quartz to some degree, the electron flow would cease after the pressure came to rest. Quartz crystal does not create energy; it just converts one kind of energy into another. Needless to say, this point in itself leads to some interesting observations regarding the characteristics of the granite complex.

Above the King's Chamber are five rows of granite beams, making a total of forty-three beams weighing up to seventy tons each. The layers are separated by spaces large enough for the average person to crawl into. The red granite beams were cut square and parallel on three sides but were left seemingly untouched on the top surface, which is rough and uneven. Some of the beams even had holes gouged into their tops.

In cutting these giant monoliths, the builders evidently found it necessary to treat the beams destined for the uppermost chamber with the same respect as those intended for the ceiling directly above the King's Chamber. Each beam was cut flat and square on three sides, with the topside rough and seemingly untouched. Petrie wrote: "The roofing beams are not of 'polished granite,' as they have been described; on the contrary, they have rough-dressed surfaces, very fair and true so far as they go, but without any pretense to

polish."

2

From his observations of the granite inside the King's Chamber, Petrie continued with those of the upper chambers: "All the chambers over the King's Chamber are floored with horizontal beams of granite, rough dressed on the under sides which form the ceilings, but wholly unwrought

above."

3

These facts are interesting, considering that the beams directly above the King's Chamber would be the only ones visible to those entering the pyramid. Even so, the attention these granite ceiling beams

received was nonetheless inferior to the attention commanded by the granite out of which the walls were constructed.

It is remarkable that the builders would exert the same amount of effort in finishing the thirty-four beams that would not be seen once the pyramid was built as they did the nine beams forming the ceiling of the King's Chamber, which would be seen. Even if these beams were imperative to the strength of the complex, deviations in accuracy would surely be allowed, making the cutting of the blocks less time consuming. Unless, of course, the builders were either using these upper beams for a specific purpose, or were using standardized machining methods that produced parts with little variation.

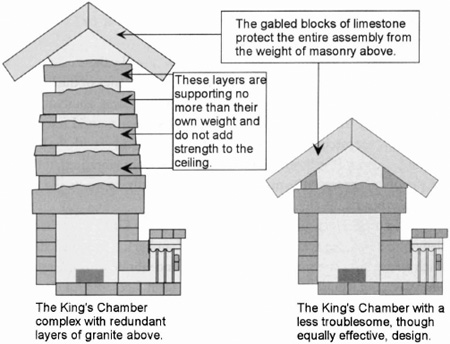

Traditional theory, proposed by Howard-Vyse and supported by Egyptologists, has it that the granite beams served to relieve pressure on the King's Chamber and allowed this chamber to be built with a flat ceiling. I disagree. The pyramid builders knew about and were already utilizing a design feature that was structurally sound on a lower level inside the pyramid. If we look at the cantilevered arched ceiling of the Queen's Chamber, we can see that it has more masonry piled on top of it than does the King's Chamber. The question could be asked, therefore, that if the builders had wanted to put a flat ceiling in this chamber, wouldn't they have needed to add only one layer of beams? For the distance between the walls, a single layer of beams in the Queen's Chamber, like the forty-three granite beams above the King's Chamber, would be supporting no more than their own weight (see Figure 36).

This leads me to ask, "Why does the King's Chamber need five layers of these beams?" From an architectural and engineering point of view, it is unnecessary to have so many monolithic blocks of granite in this structure. It is especially wasteful when we consider the amount of incredibly difficult work that must have been invested in quarrying, cutting, and transporting the stone from the Aswan quarries five hundred miles awayâand then raising the beams to the 175-foot level of the pyramid. There is surely another reason for such an enormous effort and investment of time.

And look at the characteristics of these beams. Why cut them square and flat on three sides and leave them rough on the top? If no one is going to look at them, why not make them rough on all sides? Better still, why not make all sides flat? It would certainly make them easier to assemble. It is

clear, then, that the forty-three giant beams above the King's Chamber were not included in the structure to relieve this chamber from excessive pressure from above, but were included to fulfill a more advanced purpose. When we look at these beams with an engineer's eye, we can discern a simple, yet refined technology in this granite complex at the heart of the Great Pyramid, a technology that operated this power plant.

F

IGURE

36.

Redundant Granite in King's Chamber Ceiling

The giant granite beams above the King's Chamber could be considered to be forty-three individual bridges. Like the Tacoma Narrows Bridge, each one is capable of vibrating if a suitable type and amount of energy is introduced. If we were to concentrate on forcing just one of the beams to oscillateâwith each of the other beams tuned to that frequency or its harmonicâthe other beams would be forced to vibrate at the same frequency or a harmonic. If the energy contained within the forcing frequency was great enough, this transfer of energy from one beam to the next could affect the entire series of beams. A situation could exist, therefore, in which one individual

beam, in the ceiling directly above the King's Chamber, could indirectly influence another beam in the uppermost chamber by forcing it to vibrate at the same frequency as the original forcing frequency or one of its harmonic frequencies. The amount of energy absorbed by these beams from the source would depend on the natural resonant frequency of the beam.

If this scenario is true, we have to consider the beams' ability to dissipate the energy they were subjected to, as well as their natural resonating frequency. If the forcing frequency (sound input) coincided with the beams' natural frequency (the beams were not restrained from vibrating), then the transfer of energy would be maximized. Consequently, so would the vibration of the beams.

We know that the giant granite beams above the King's Chamber have a length of seventeen feet (the width of the chamber), the entire length of which we assume can react to induced motion and vibrate without restraint. Some damping would occur if the beams' adjacent faces were so close that they rub together. However, if the beams vibrate in unison, it is possible that such damping would not happen. To perfect the ability of the forty-three granite beams to resonate with the forcing frequency, the natural frequency of each beam would have to be of the same frequency as the forcing frequency, or be in harmony with it.

It would be possible for us to tune a length of granite, such as those found in the Great Pyramid, by altering its physical dimensions. We could attain a precise frequency by either altering the length of the beamâas a guitarist alters the length of a guitar stringâor by removing material from the beam's mass, as in the tuning of bells. (A bell is tuned to a fundamental hum and its harmonics by removing metal from critical areas.) If we would strike the beam, as one would strike a tuning fork, while it is being held in a position similar to that of the beams above the King's Chamber, we could induce oscillation of the beam. Then we could sample the frequency of the beam's vibration and remove more material until the correct frequency was reached.

Rather than suffering from a lack of attention, therefore, the rough top surfaces of those granite beams in the King's Chamber have been given more careful and deliberate attention and work than the beams' sides or bottoms. Before the ancient craftspeople placed them inside the Great Pyramid, each beam may have been "tested" or "tuned" by being suspended on each end in

the same position that it would have once it was placed inside the pyramid (see Figure 37). The workers would then shape and gouge the topside of each beam in order to tune it before it was permanently positioned inside the pyramid. After cutting three sides square and true to each other, the remaining side could have been cut and shaped until it reached a specific resonating frequency. The removal of material on the upper side of the beam would take into consideration the elasticity of the beam, as a variation of elasticity might result in more material being removed at one point along the beam's length than at another. The fact that the beams above the King's Chamber are all shapes and sizes would support this speculation. In some of the granite beams, I would not be surprised if we found holes gouged out of the granite as the tuners worked on trouble spots. What we find in the King's Chamber, then, are thousands of tons of granite that were precisely tuned to resonate in harmony with the fundamental frequency of the Earth and the pyramid!