The Gestapo and German Society: Enforcing Racial Policy 1933-1945 (10 page)

Read The Gestapo and German Society: Enforcing Racial Policy 1933-1945 Online

Authors: Robert Gellately

Tags: #History, #Europe, #Germany, #Law, #Criminal Law, #Law Enforcement, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Politics & Government, #International & World Politics, #European, #Specific Topics, #Social Sciences, #Reference, #Sociology, #Race Relations, #Discrimination & Racism

to the recollections of many who once lived in Nazi Germany, the effectiveness of the Gestapo and the surveillance system rested on the large 'army' of spies and paid informers at the disposal of local officials.'

It is true that the citizen never felt far from the gaze of Nazis, whether in public, at work, or even at home. However, this sense of being watched could not have been due to the sheer physical presence of Gestapo officials. Membership in the Gestapo was in fact remarkably small.

By the end of 1944 there were approximately 32,000 in the force, of whom 3,000 were administrative officials, 15,500 or so executive officials, and 13,500 employed workmen, 9,000 of whom were draftees. Those in 'administration' had the same training as other civil servants, and dealt with issues such as personnel records, budget, and supplies, and legal problems such as those stemming from passport law. The 'executive officials', especially trained in the 'leader school' (Fiihrerschule) were assigned tasks according to the various desks (Referate) into which the Secret Police was subdivided. These officials 'executed the real tasks of the Gestapo as laid down by law', although 'a number of these officials also were engaged in pure office work'.'

The Gestapo also took over other organizations and some of their personnel, such as the customs frontier guard, and so on, but these had little to do with the day-to-day policing inside Germany, and can be left out of account here. Otto Ohlendorf, head of the SD, put the total membership in the Gestapo at 30,000, but included not only those stationed outside Germany proper, but also the assistants, workers, and office personnel; he estimated that most were in the administrative or support staff, with 'one specialist' or executive official 'to three or four persons' in the Gestapo.'

Just how it happened that people in Nazi Germany could have come to feel that spies were just about everywhere will be taken up later. At this point it is worth while to look at the organizational forms taken by the Gestapo and the police network at the local level.

1. ORGANIZATION OF THE LOCAL GESTAPO

Given the small number of officials in the Gestapo, their distribution had to be thin on the ground. A survey in March 1937 of personnel for the entire area within the Dusseldorf Gestapo region showed a total of 291 persons, of whom 49 were concerned with administrative matters and 242 involved in police work (in `Aul3endienst'). At that time 126 officials were stationed in Dusseldorf, a city with a population of approximately 500,000. Other cities within the overall jurisdiction of the Dusseldorf headquarters were assigned additional personnel: Essen had 43 officials to cover a population of about 650,000 while Wuppertal had 43 and Duisburg 28, for populations in excess of 400,000. Oberhausen had 14 officials, Munchen-Gladbach I I, while Kleve and Kaldenkirchen, with 8 each, were the smallest two of the eight cities in the jurisdiction to have their own Gestapo posts; the many other cities of the area did not have such posts. In comparison with the rest of the country, numbers for Dusseldorf were relatively large, partly because of the 165kilometre national border for which it was responsible.'

Still, given the demands made by the regime, this was a small force to police the roughly 4 million inhabitants of the jurisdiction-known for its support of opposition parties such as the SPD and KPD, and for being a haven of `political Catholicism', and with relatively large Polish and Jewish populations.

The range of political behaviour that came within the sphere of the Gestapo was large and constantly growing. The desk in the Dusseldorf Gestapo con

cerned with Polish and eastern workers as of 15 July 1943 had twelve separate subsections dealing with everything from 'refusal to work' and 'leaving the workplace without permission' to 'forbidden sexual relations'. The section on the 'Economy' was divided into eight subsections. While the regular police were in charge of enforcing economic regulations brought in for the duration of the war, the Gestapo was to be called in when, for example, the deed caused unrest in the population or when the perpetrator was a public figure.'

Outside the largest cities, such as Berlin, Hamburg, or Munich, the various desks (Referate) in any given local Gestapo might comprise only a single official, and in many places this person had to look after more than one desk.'

At Koblenz, for example, it was recalled that the one man who was to deal with the Jews also looked after Freemasonry.'

In Darmstadt the man in the Judenreferat was entirely on his own, and had difficulty even getting a secretary until after the regime began to step up its official anti-Semitism.'

Even in large cities such as Dusseldorf it was claimed that there was one man in charge of the Jewish section (an Oberinspektor), with `two or three assistants'.I`

2. THE EVERYDAY OPERATION OF THE GESTAPO

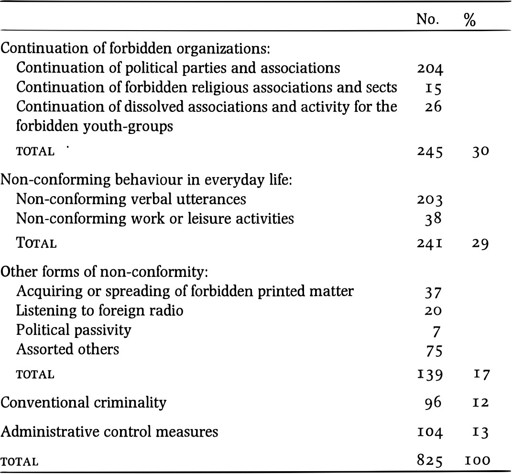

The work of the late Reinhard Mann makes possible some general statements about Gestapo activities. Mann studied a random sample of 825 cases drawn from the 70,000 surviving files of the Dusseldorf Gestapo. Apart from Wi rzburg, whose files are dealt with in detail below (beginning in Chapter 5), these kinds of documents have not survived for any other Gestapo post.12

A brief examination of Mann's random sample will give some idea of the routine operations of the Gestapo.

TABLE 1. Proceedings of the Dusseldorf Gestapo 1933-1945

Source: R. Mann, Protest and Kontrolle, 18o.

Table i, which is taken from Mann's study, shows the preoccupations of the Dusseldorf Gestapo over the course of the Nazi dictatorship. From his sample, 245 (30 per cent of all cases) pertained to tracking prohibited, mostly

left-wing, organizations. Of the 204 cases of people involved in illegal political parties or organizations, 61 pertained to those suspected of links with the KPD and 44 with the SPD; in 69 cases it was not possible to establish specific political affiliation. When it came to organized political parties, the main opponents were clearly the Marxists. The pursuit of religious-oriented or youth organizations took a much smaller share of the Gestapo

The efforts to track illegal organizations show an increase from 19 3 3 (when 14 of the 245 cases came to light); the highest number of such cases began in 1935, with 57 cases, up from 30 the year before. Then a more or less steady decline set in. In 1937 42 cases were opened, but next year the number fell to 18, with only 13 in the following year; after a brief flurry in 1940, the drop continued, with only 2 in 1941. There were 7 cases in 1942, 4 in 1943, and I in 1944.14

The declining number of cases after 1935 reflects the success of the Gestapo in eliminating organized opposition.

The Dusseldorf Gestapo pursued nearly as many persons suspected of 'nonconforming everyday behaviour'-29 per cent of all its cases-as it did in its efforts to deal with outlawed organizations. Much energy was expended in controlling the spoken word in Nazi Germany, as most instances of nonconformity brought to Gestapo attention (203 cases out of 241) pertained to airing opinions in public. (More will be said about this matter later.) The Gestapo was also involved in regulating work and leisure activities. Many of the 241 cases in this category had to depend heavily on the co-operation of people beyond the ranks of the Secret Police who brought information; there were too few Gestapo members to accomplish this kind of policing on their own.

The Gestapo was keen to enforce policies with regard to obtaining and/or spreading information disallowed by the regime. Fifty-seven cases (7 per cent of the total) concerned such matters. Other forms of non-conformity'political passivity' and a wide variety of deviations lumped together as 'other kinds' of non-conformity-took up nearly 1 o per cent of the Gestapo caseload. The last-named category, with 75 cases, is a catch-all which contains everything from the Hitler caricaturist, to the reluctant military recruit of 'mixed race', to the Catholic school rector denounced for insufficient Nazi zeal.

15 It is evident that the Gestapo was operating with a concept of opposition and security which went well beyond conventional definitions. There were 104 cases (13 per cent of the total) brought to the attention of the Gestapo upon suspicion that someone had broken 'administrative control measures'bending or breaking rules concerning residency requirements, for example.

Because crime was to some extent politicized, the Gestapo spent much effort (12 per cent of all its cases) in dealing with what in Table i is called

'conventional criminality'. They investigated accusations involving 'morals charges' and falsifications to the authorities. Indeed, local Gestapo officials were at times utterly ruthless and single-minded when it came to prosecuting homosexuals, especially if they were Jews.16

Of all the 'conventional' offences it investigated, however, the largest single category was 'economic' charges of various kinds. An examination of the Dusseldorf files themselves shows that before 1939 there were efforts to stop the smuggling of money over the border into Holland or Belgium, and when the war came there was great concern to enforce the special measures introduced to regulate the economy."

Mann's quantitative analysis of Gestapo activities is useful, in that it suggests in broad outline something about the Gestapo workload and routine operation. This work-which his untimely death in 19 8 r prevented him from completing-has limitations for the present study on the enforcement of racial policy, however, since Mann excludes certain categories of Gestapo case-files, namely those which pertain to `racially foreign' groups such as the Jews and foreign workers. These limitations are examined below in Chapter 5.

A preliminary comparison of Dusseldorf and Wurzburg reveals a remarkable similarity in the organization and modus operandi of the Gestapo. This finding is to be expected, given the efforts that were made to achieve central control. But the preoccupations of the local Gestapo varied according to the local circumstances. One obvious and persistent concern of the Dusseldorf Gestapo, which emerges with especial clarity in contrast to the Wurzburg post, is that the Gestapo in the Rhineland had to spend much effort in policing both the River Rhine and the border, with regard to the flow of people, goods, and money. The border is far away from Wurzburg, and thus is hardly mentioned in the files. Nor were the illegal Communist and Socialist movements anything like as important in the largely agricultural and rural Wurzburg area as they were in the Rhineland, and the Gestapo divided its resources accordingly. Wurzburg officials had more time to deal with the pettiest infringements when it came to the Jews. Similar charges were laid and followed up in Dusseldorf, but for the most part they seem not to have been taken up with quite the same zeal as in Wurzburg. Other local variations in the Gestapo routine undoubtedly existed-for example, in places which had neither Jews nor much of an illegal workers' movement. In Dusseldorf and Wurzburg Catholicism and policing the pulpit were also of great importance, and countless priests were hauled in for minor infractions.