The Genius in All of Us: New Insights Into Genetics, Talent, and IQ (6 page)

Read The Genius in All of Us: New Insights Into Genetics, Talent, and IQ Online

Authors: David Shenk

Tags: #Psychology, #Cognitive Psychology & Cognition, #Cognitive Psychology

In 1916, Stanford’s Lewis Terman produced a practical equivalent of

g

with his Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scales

(

adapted from an earlier version by French psychologist Alfred Binet

) and declared it to be the ideal tool to determine a person’s native intelligence. While some immediately saw through Terman’s claim,

2

most greeted IQ with enthusiasm. The U.S. Army quickly adopted a version for recruiting, and schools followed. Everything about IQ’s crispness and neat classifications fit perfectly with the American hunger for enhanced social, academic, and business efficiencies.

Unfortunately, that same meritocracy movement carried an underbelly of profound racism in which alleged proof of biological superiority of white Protestants was used to keep blacks, Jews, Catholics, and other groups out of the higher ranks of business, academia, and government. In the early 1920s,

the National Intelligence Test (a precursor to the SAT) was designed by Edward Lee Thorndike

, an ardent eugenicist determined to convince college administrators how wasteful and socially counterproductive it would be to provide higher education to the masses. “The world will get better treatment,” Thorndike declared, “by trusting its fortunes to its 95 or 99-percentile intelligences.” Interestingly, just a few years later, the SAT’s creator,

Princeton psychologist Carl Brigham, disavowed his own creation, writing that all intelligence tests were based on “one of the most glorious fallacies in the history of science, namely that the tests measured native intelligence purely and simply without regard to training or schooling

.”

Aside from overt ethnic discrimination, the real and lasting tragedy of IQ and other intelligence tests was the message they sent to every individual—including the students who scored well. That message was:

your intelligence is something you were given, not something you’ve earned

. Terman’s IQ test easily tapped into our primal fear that most of us are born with some sort of internal restraining bolt allowing us to think only so deeply or quickly. This is extraordinary, considering that,

at its core, IQ was merely a population-sorting tool

.

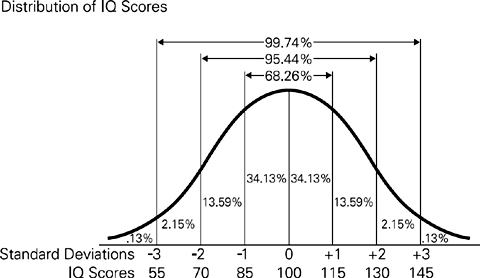

Courtesy of Hadel Studio

IQ scores

do not actually report how well you have objectively mastered test material. They merely indicate how well you have mastered it compared to everyone else. Given that it simply ranked individuals in a population, it is particularly sad to look back and see that

Lewis Terman and colleagues actually recommended that individuals identified as “feebleminded” by his test be removed from society and that anyone scoring less than 100 be automatically disqualified from any prestigious position

. To automatically dismiss the worth of anyone scoring below 100 was to mistake relative value for absolute value. It was like saying that, out of any one hundred oranges, fifty are never going to taste very good.

IQ did succeed admirably in one regard: it standardized academic comparisons and thus became a very useful way of comparing academic achievement across schools, states, even nations. Any school principal, governor, etc., would certainly want to know whether his students were underperforming or outperforming the national average. Further, these tests measured achievement broadly enough to predict generally how test takers would fare in the future, compared to others.

But measuring achievement was enormously different from pinpointing individual capacity. Predicting how most kids will do is entirely different from declaring what any particular kid

can

do. “Stability,” Exeter University’s Michael Howe points out,

“does not imply unchangeability

.” And indeed, individual IQ scores are quite alterable if a person gets the right push.

“IQ scores,” explains Cornell University’s Stephen Ceci, “can change quite dramatically as a result of changes in family environment (Clarke, 1976; Svendsen, 1982), work environment (Kohn, 1981), historical environment (Flynn, 1987), styles of parenting (Baumrind, 1967; Dornbusch, 1987), and, most especially, shifts in level of schooling

.”

In 1932, psychologists Mandel Sherman and Cora B. Key discovered that IQ scores correlated inversely with a community’s degree of isolation: the higher the cultural isolation, the lower the scores. In the remote hollow of Colvin, Virginia, for example, where most adults were illiterate and access to newspapers, radio, and schools was severely limited, six-year-olds scored close to the national average in IQ. But as the Colvin kids got older, their IQ scores drifted lower and lower—falling further and further behind the national average due to inadequate schooling and acculturation. (The very same phenomenon was discovered among the so-called canal boat children in Britain and in other isolated cultural pockets).

Their unavoidable conclusion was that “children develop only as the environment demands development

.”

Children develop only as the environment demands development

. In 1981, New Zealand–based psychologist James Flynn discovered just how profoundly true that statement is.

Comparing raw IQ scores over nearly a century, Flynn saw that they kept going up

: every few years, the new batch of IQ test takers seemed to be smarter than the old batch. Twelve-year-olds in the 1980s performed better than twelve-year-olds in the 1970s, who performed better than twelve-year-olds in the 1960s, and so on. This trend wasn’t limited to a certain region or culture, and the differences were not trivial. On average,

IQ test takers improved over their predecessors by three points every ten years

—a staggering difference of eighteen points over two generations.

The differences were so extreme, they were hard to wrap one’s head around.

Using a late-twentieth-century average score of 100, the comparative score for the year 1900 was calculated to be about 60—leading to the truly absurd conclusion, acknowledged Flynn, “that a majority of our ancestors were mentally retarded

.” The so-called Flynn effect raised eyebrows throughout the world of cognitive research. Obviously, the human race had not evolved into a markedly smarter species in less than one hundred years. Something else was going on.

For Flynn, the pivotal clue came in his discovery that the increases were not uniform across all areas but were concentrated in certain subtests. Contemporary kids did not do any better than their ancestors when it came to general knowledge or mathematics. But in the area of abstract reasoning, reported Flynn, there were “huge and embarrassing” improvements. The further back in time he looked, the less test takers seemed comfortable with hypotheticals and intuitive problem solving. Why? Because a century ago, in a less complicated world, there was very little familiarity with what we now consider basic abstract concepts.

“[The intelligence of] our ancestors in 1900 was anchored in everyday reality,” explains Flynn

. “We differ from them in that we can use abstractions and logic and the hypothetical … Since 1950, we have become more ingenious in going beyond previously learned rules to solve problems on the spot.”

Examples of abstract notions that simply didn’t exist in the minds of our nineteenth-century ancestors include the theory of natural selection (formulated in 1864), and the concepts of control group (1875) and random sample (1877)

. A century ago, the scientific method itself was foreign to most Americans. The general public had simply not yet been conditioned to think abstractly.

The catalyst for the dramatic IQ improvements, in other words, was not some mysterious genetic mutation or magical nutritional supplement but what Flynn described as “the [cultural] transition from pre-scientific to post-scientific operational thinking.” Over the course of the twentieth century, basic principles of science slowly filtered into public consciousness, transforming the world we live in. That transition, says Flynn, “represents nothing less than a liberation of the human mind.”

The scientific world-view, with its vocabulary, taxonomies, and detachment of logic and the hypothetical from concrete referents, has begun to permeate the minds of post-industrial people. This has paved the way for mass education on the university level and the emergence of an intellectual cadre without whom our present civilization would be inconceivable.

Perhaps the most striking of Flynn’s observations is this

: 98 percent of IQ test takers today score better than the average test taker in 1900. The implications of this realization are extraordinary. It means that in just one century, improvements in our social discourse and our schools have dramatically raised the measurable intelligence of almost

everyone

.

So much for the idea of fixed intelligence. We know now that, even though most people’s relative intellectual ranking tends to remain the same as they grow older:

It’s not biology that establishes an individual’s rank to begin with (social, academic, and economic factors are well-documented contributors).

No individual is truly stuck in her original ranking.

Every human being (even a whole society) can grow smarter if the environment demands it.

None of this has dissuaded proponents of innate intelligence, who continue to insist that IQ’s stability proves a natural, biological order of minds: the gifted few naturally ascend to greatness while those stuck at the other end of the spectrum serve as an unwanted drag on modern society.

“Our ability to improve the academic accomplishment of students

in the lower half of the distribution of intelligence is severely limited,” Charles Murray wrote in a 2007 op-ed in the

Wall Street Journal

. “It is a matter of ceilings … We can hope to raise [the grade of a boy with an IQ slightly below 100]. But teaching him more vocabulary words or drilling him on the parts of speech will not open up new vistas for him. It is not within his power to follow an exposition written beyond a limited level of complexity … [He is] not smart enough.”

“Even the best schools under the best conditions cannot repeal the limits

on achievement set by limits on intelligence,” Murray says bluntly.

But an avalanche of ongoing scholarship paints a radically different, more fluid, and more hopeful portrait of intelligence.

In the mid-1980s, Kansas psychologists Betty Hart and Todd Risley realized that something was very wrong with Head Start, America’s program for children of the working poor. It manages to keep some low-income kids out of poverty and ultimately away from crime. But for a program that intervenes at a very young age and is reasonably well run and generously funded—$7 billion annually—it doesn’t do much to raise kids’ academic success. Studies show only

“small to moderate

” positive impacts on three- and four-year-old children in the areas of literacy and vocabulary, and no impact at all on math skills.

The problem, Hart and Risley realized, wasn’t so much with the mechanics of the program; it was the

timing

. Head Start wasn’t getting hold of kids early enough. Somehow, poor kids were getting stuck in an intellectual rut long before they got to the program—before they turned three and four years old. Hart and Risley set out to learn why and how. They wanted to know what was tripping up kids’ development at such an early age. Were they stuck with inferior genes, lousy environments, or something else?