The Genius and the Goddess (15 page)

Read The Genius and the Goddess Online

Authors: Jeffrey Meyers

Toward the end of 1943 Miller was offered $750 a week to write

a screenplay based on Ernie Pyle's frontline war dispatches during the

Italian campaign. His film

script was rewritten and made into the

successful

Story of GI Joe

(1945) with Burgess Meredith and Robert

Mitchum. Miller got no screen credit; but his first book,

Situation

Normal

(1944), about the problems that soldiers had when they returned

from combat and tried to adjust to civilian life, grew out of his research

for the Ernie Pyle film. This book was dedicated to his older brother,

Kermit, who was serving as a lieutenant in the American army.

Miller's editor,

Frank Taylor, at the highbrow publishers Reynal &

Hitchcock, was a tall, handsome, stylish man. He had serious left-wing

views and socialized with politically committed artists at his

home in Greenwich Village. Taylor became a close friend and, later

on, the producer of

The Misfits

. He also published

Focus

(1945), Miller's

only novel, with the fashionable postwar theme of alienation. The

central character is a gentile whose new glasses make him look Jewish.

His appearance provokes anti-Semitic hostility, and he at first tries to

maintain his non-Jewish status. Eventually he accepts his new identity

and fights against the prejudice he's encountered. The subject of

anti-Semitism was especially relevant between the liberation of the

Nazi extermination camps in 1945 and the founding of the state of

Israel in 1948. Readers were eager for serious fiction after the war

and

Focus

(according to Miller) sold a surprising 90,000 copies.

Miller disliked his mother-in-law's flat, unemphatic Ohio speech

and her Catholic belief that earthly life was a disaster. But she told

him the story that inspired

All My Sons

, his first triumphant success

in the theater. A local newspaper reported that during the war the

Wright Aeronautics Corporation of Ohio had bribed army inspectors

to approve defective airplane engines. The novelist and critic

Mary McCarthy pointed out that Miller used Henrik Ibsen's device

of the fatal secret, in which crime and guilt enter an ordinary domestic

scene and build up to a tragic climax. She observed that "

All My Sons

was a social indictment taken, almost directly, from Ibsen's

Pillars of

Society

[1877]. The coffin ships, rotten, unseaworthy vessels caulked

over to give the appearance of soundness, become defective airplanes

sold to the government by a corner-cutting manufacturer during the

Second World War." Other critics noted the influence of

Ibsen's

An

Enemy of the People

(1882), which Miller adapted for the American

stage in 1950. In this play, "an idealistic doctor discovers that the spring

waters from which his spa town draws its wealth are dangerously

contaminated. As Stockmann's fellow citizens realize the financial implications

of his research, he comes under increasing pressure to keep

silent."

In Miller's realistic tragedy – brilliantly directed for the stage by

Elia Kazan and starring Ed Begley and Arthur Kennedy – Joe Keller

sells cracked cylinder heads to the Army Air Force, which cause a

number of fatal plane crashes. He also allows his employee and neighbor

to take the blame and go to jail. When Keller's son, a pilot, dies in

the war, his younger son tells Keller that his brother had discovered

the fatal secret and committed suicide out of shame. Appalled by his

own greed, and faced with the ruin of his name, business and family,

Keller finally accepts his guilt and kills himself. After Miller won the

Drama Critics' Circle Award for the best new American play of the

season, and several reviewers suggested that the director and actors

were more responsible for its success than the author, he ironically

remarked, "Everyone's son but mine!" His sudden fame attracted attention

in Hollywood and in 1947 he was offered, but turned down,

$2,500 to write the screenplay for Alfred Hitchcock's

Rope

, made the

following year with James Stewart and Farley Granger.

In a frenzy of inspiration Miller wrote the first act of his best-known

play,

Death of a Salesman

, in less than twenty-four hours. The

play, again directed by Kazan, starred Lee J. Cobb and Mildred Dunnock

as Willy and Linda Loman, Arthur Kennedy and Cameron Mitchell

as their sons. Like

All My Sons

, it was a domestic tragedy that portrayed

the rivalry of two brothers, a loyal wife and a father who kills himself.

Willy's brother Ben, a ruthlessly successful figure who thrives in a

cutthroat world, makes a dream-like appearance. No one has noticed

that the exotic, authoritarian Ben was inspired by Kurtz in

Joseph

Conrad's

Heart of Darkness

(1899). Marlow, who's been sent upriver

and into the jungle to rescue the pitiless and fanatical Kurtz, says with

a mixture of awe and condemnation that Kurtz "had collected, bartered,

swindled, or stolen more ivory than all the other agents together."

Ben boasts to Willy, a weak failure: "When I was seventeen I walked

into the jungle, and when I was twenty-one I walked out. And by

God I was rich."

6

Ben, a modern-day Kurtz, is more interested in

accumulating fabulous wealth than exerting absolute power. He feels

a sense of pure triumph rather than horrified remorse about exploiting

the natives and tearing the riches out of the African earth.

Miller earned a fabulous $160,000 a year from the New York

production of

Salesman

and an equal amount from several touring

companies. Always careful with money, he now lashed out by buying

a house in Brooklyn Heights, a farm in Connecticut and a new car.

When Frank Taylor sent Miller's script to Dore Schary at MGM and

suggested he buy the film rights, Schary called it "the most depressing

fucking thing I ever read. Nobody would ever want to see this kind

of film." The play won the Pulitzer Prize, and became a film in 1951,

with Fredric March playing Willy, Kevin McCarthy his son Biff, and

Dunnock and Mitchell reprising their Broadway roles. It is widely

taught in schools and colleges, and by 2005 had sold more than eleven

million copies.

Miller was a

reserved, guarded and withdrawn man who rarely showed

his deepest feelings. He was a cool and distant father, had few close

friends and eventually broke with his most intimate companions: with

Elia Kazan for political reasons and with Norman

Rosten for siding

with Marilyn after their divorce. Miller also pulled Marilyn away from

her own friends. He persuaded her to sever relations with Milton and

Amy Greene, and tried to diminish the pernicious influence of Lee

and Paula Strasberg.

Miller's dedications shed some light on his limited friendships.

Many of his books had no dedications; and sixteen of his twenty-one

dedications were given to his family: to his brother, three wives, three

children and his third wife's parents (but not to his own father and

mother). Of the remaining five dedications,

Theater Essays

was dedicated

to his college playwriting teacher

Kenneth Rowe;

All My Sons

to Kazan; and

A View from the Bridge

to the writer and translator James

Stern "for his encouragement." Two other books were dedicated to

people who had recently died:

I Don't Need You Any More

to the

memory of his editor at Viking,

Pascal Covici, and

The Misfits

"to

Clark Gable, who did not know how to hate."

Several colleagues were irritated by Miller's characteristic pompous

and

self-righteous rectitude.

Harold Clurman, a founder of the Group

Theater and director of Miller's

Incident at Vichy

, observed that "Miller,

earnest and upright, is sustained by a sense of mission. . . . For all his

unbending seriousness and a certain coldness of manner, there is more

humor in him than is generally supposed. He is much less rigid now

than he is said to have been in his younger days, when he put people

off."

Robert Lewis directed Miller's adaptation of

An

Enemy of the

People

, which starred the married couple,

Florence Eldridge and

Fredric

March. Lewis recalled that on one occasion Miller, who took an active

part in the production of his plays and was usually self-controlled,

unexpectedly exploded:

Arthur sensed this wish of Florence's to be loved by the audience.

Blowing his top in the middle of a scene one day at a

run-through, Arthur yelled up to Mrs. March, "Why must you

be so fucking noble?" . . . Florence flew off the stage and into

her dressing room, followed by her equally anguished husband.

The Marches insisted neither of them would return to the

production until Arthur apologized in front of the company.

The playwright compromised by offering a private apology,

and the Marches finally accepted that.

7

Kazan shrewdly remarked that after the tremendous success, wealth

and fame of

Salesman

, Miller's "eyes acquired a new flash and his

carriage and movement a hint of something swashbuckling." Frank

Taylor's wife, Nan, added that "Mary, never an extrovert, began to

fade into his background, 'meek . . . beside him.'" Lacking insight into

Mary's character and their marriage, Miller confessed that "it never

occurred to me that she might have felt anxious at being swamped

by this rush of my fame." For years Mary had loyally believed in his

talent, and helped support him both intellectually and financially. But

now that his career had taken off and he had plenty of money, he

was less dependent on her. As he developed artistically and socially,

and saw sexual possibilities that never existed before, she rather desperately

clung to their old way of life.

Long before he met Marilyn, Miller's marriage was strained and

unhappy. A crucial incident in 1943, four years before his fame, revealed

Mary's puritanical nature. Extremely intolerant and censorious, she

took the thought for the deed when he merely fantasized about other

women. While discussing the Ernie Pyle project in Washington, Miller

was introduced to an attractive war widow, who excited him by

confiding that she'd compensated for her loss by sleeping with a

number of young sailors. When, Miller wrote, "I blithely told Mary

of my attraction to this woman, saying that had I not been married

I would have liked to sleep with her," his mild confession "was received

with such a power of disgust and revulsion . . . that her confidence

in me, as well as my mindless reliance on her, was badly damaged."

8

Mary's reaction to his affair with Marilyn was even more furious; and

his next two plays were suffused with his own shame and guilt.

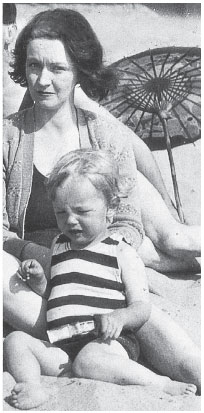

1. Norma Jeane and her

mother, Gladys Baker,

Los Angeles beach, 1928

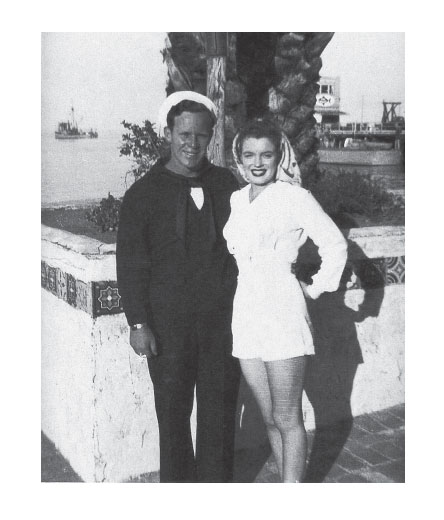

2. Norma Jeane and

her first husband,

Jim Dougherty, 1943

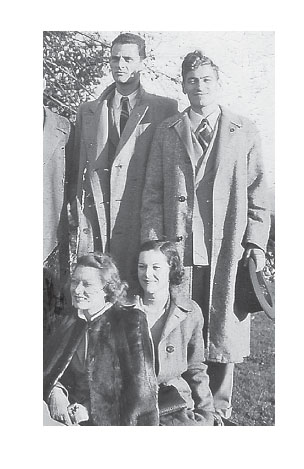

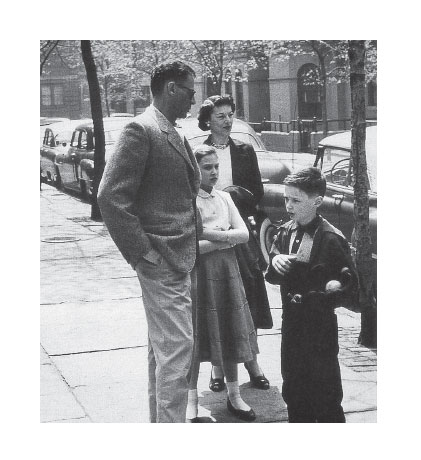

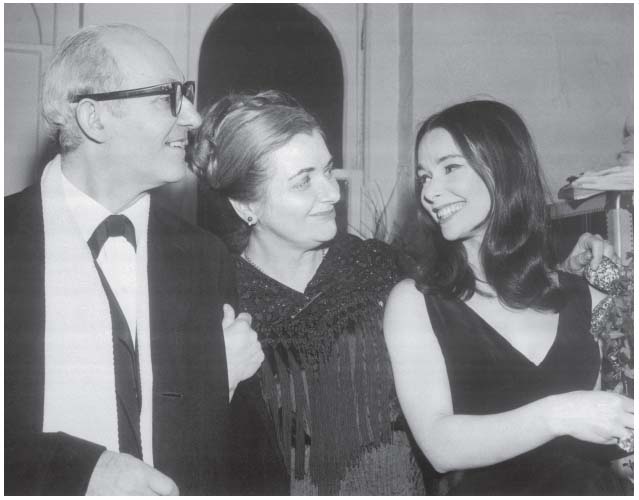

3. Arthur Miller, Norman Rosten,

Hedda Rosten and

Mary Slattery Miller, 1940

4. Miller with Mary

and his children,

Jane and Robert, 1953

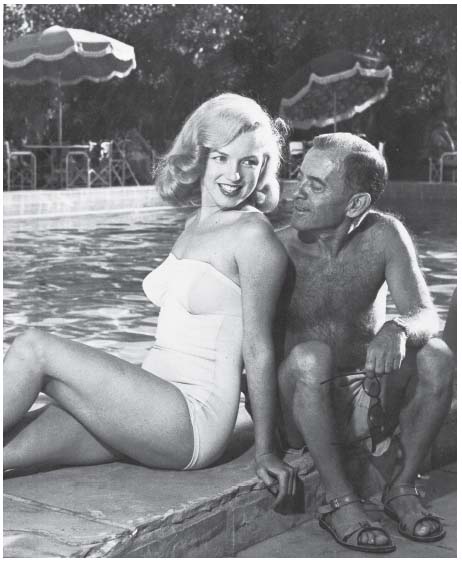

5. Marilyn and

Johnny Hyde,

late 1949

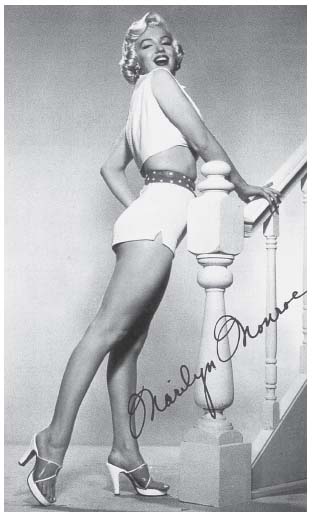

6. Marilyn

and Natasha

Lytess,

c

. 1952

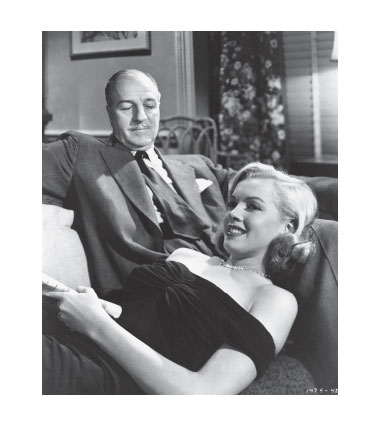

7. Marilyn and Louis Calhern

in

The Asphalt Jungle

, 1950

8. Marilyn with Anne Baxter, Bette Davis and George Sanders in

All About Eve

, 1950

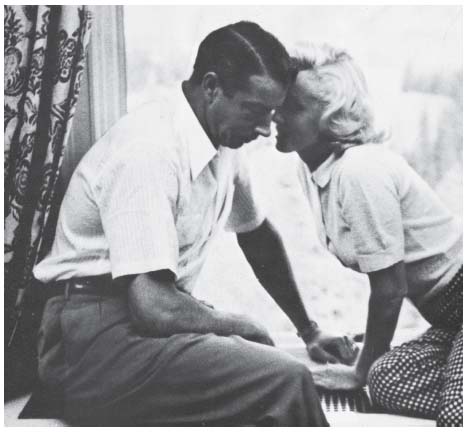

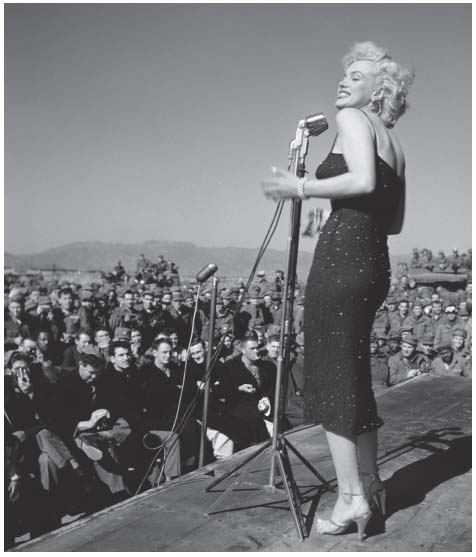

9. Marilyn and

Joe DiMaggio, 1953

10. Marilyn

entertaining

troops in Korea,

February 1954

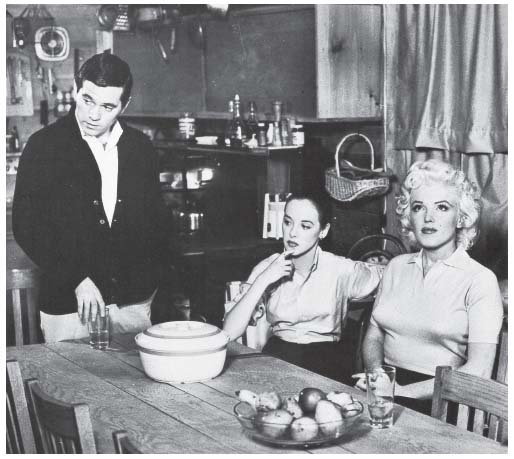

11. Marilyn with

Milton and Amy

Greene, 1955

12. Lee, Paula and Susan Strasberg, 1963

13. Marilyn in airport bathroom,

April 1955