The Galloping Ghost (32 page)

Read The Galloping Ghost Online

Authors: Carl P. LaVO

Despite it all, Scouting had rebounded and was to double its enrollment from preâWorld War II levels to more than two million in just a few years.

In 1956 the Fluckeys relocated to Annapolis, where Gene headed the electrical engineering department at the academy. The couple left Barbara behind to attend the University of California at Berkeley.

As Gene settled in to his new responsibilities, Rear Adm. William R. Smedberg, III, became superintendent of the academy. He was aware that the Naval Academy Athletic Association owned 101 acres west of the campus on which it hoped one day to build a football stadium. The association, founded in 1892, had collected $1.5 million over the years to put toward it. In the mid 1950s college football was growing in popularity and the Navy team was poised to challenge for national championships. Smedberg calculated that the time was right to build the stadium and that another $2.2 million was needed for a facility that would seat thirty thousand spectators. He thought the money could be raised with a dedicated fundraising effort and approached Navy Secretary Thomas S. Gates for his support. Gates, however, thought it was impossible to raise the money privately and that no money could be expected from Congress. When the admiral persisted, the secretary finally gave in. “Well, Smeddy, okay, I'll give you a trial, but do you have any idea how much $2.2 million is in ten-dollar and fifteen-dollar and twenty-dollar and twenty-five-dollar amounts?”

What Gates didn't know was that Smedberg had a secret weapon. “Fortunately, I had this most magnificent head of department, Gene Fluckey, who was a great submarine wartime hero, one of the greatest, I think, we ever had, Congressional Medal of Honor winner in submarines, who was the head of my fund drive.”

Fluckey approached the task with meteoric fervor. “He had a brilliant idea a minute,” said the admiral. “I was constantly being pushed and prodded to do things I wouldn't really ever have done myself.” Things like putting a Cadillac and a Ford Thunderbird sports car in the middle of the

academy to be raffled off. And a brand-new speed boat. A sail boat. And a Piper aircraft. All Fluckey ideas. Volunteers stood long hours, day after day, selling tickets beside each of the raffle items set up all over the campus. Only one prize would be awarded. Net proceeds: $75,000. That was just the beginning.

Fluckey's full-court-press put Smedberg on the griddle occasionally. “One day I got a call from Don Felt, who was the vice chief of Naval Operations, and he said, âSmedberg, what the hell are you trying to do?' I said, âWhat do you mean, Don?' He said, âThis whole Pentagon is filled with midshipmen selling raffle tickets for your god-damned stadium. Get them out of here. Don't you know it's against the law?' ”

Which it was in D.C. but not in Maryland.

Commander Fluckey forged ahead, soliciting contributions from corporations, movie studios, and advertising agencies. Billboards, car bumper placards, radio spots, TV commercials, and newspaper stories sprouted everywhere. Columbia recording artist Mitch Miller and the Naval Academy Choir cut a special wax recording of “Anchors Aweigh” backed by the “Marine Corps Hymn.” One million discs were distributed to 3,700 deejays across the United States and a thousand local naval districts. A contribution of one dollar earned a patron a record, all proceeds going to the stadium fund. Fluckey also lined up testimonials, all the time soliciting new ideas. He enlisted the help of Endorsements, a public relations firm in New York, and studied such articles as “Ten Rules for Believable Testimonials” from

Advertising Requirements

magazine. The captain arranged for Admiral Smedberg to appear on a national TV broadcast of “Person-to-Person” hosted by Edward R. Murrow, on which the admiral made a pitch for the stadium. Checks for a hundred dollars, two hundred dollars, five hundred dollars soon began rolling in. Fluckey also persuaded a Hollywood studio to film a movie skit with Burt Lancaster, Clark Gable, and Smedberg for use at halftime during football games, encouraging more contributions. The campaign percolated with energy and ideas. One was for memorial chairs in the new stadium for a hundred dollars a pop. Captain Fluckey was assertive, looking for donations in every possible place. When he was in Washington with the secretary of the navy to convince flag officers to contribute a hundred dollars each, he turned to the secretary and said, “Mr. Secretary, I don't have your check.” Gene got the check.

Fluckey coined the term “Concrete with Heart” in a four-paragraph appeal to Navy sailors and Marines everywhere to get behind the push. “The Navy-Marine Corps Memorial Stadium,” he wrote, “is much more than just a football field. It is the only single memorial to the Navy and Marine

Corps. The facade will be adorned with memorial plaques. State flags will fly from its highest points. Its balconies facing the field will be emblazoned with famous battles, such as Belleau Woods, Midway, Tarawa, Coral Sea, Iwo Jima, Inchon, etc. It will be an inspiration to every American who passes though its portals.”

The appeal evoked an outpouring of contributions. Said one Marine sergeant in San Diego, “I'm the biggest dang Marine in the U.S., so here's my whole big pay check for the biggest memorial we've needed for so long.” Another donor sent in what he could, with this note: “Dear Admiral. I'm 11 years old. I earned this dollar shoveling snow. I hope someday to play in our stadium.”

Fluckey campaigned relentlessly, taking his quest international with ads in foreign periodicals. He made a personal pitch to Navy commanders at sea. He conceived a competition among them to raise the most money. Gates to the stadium were to be named after winning fleets. The rush was onâsometimes to the extreme.

Adm. Wallace C. Beakley, commander of the Seventh Fleet, got into a fierce rivalry with Adm. Charles R. “Cat” Brown's Sixth Fleet. Beakley was determined to win, even sending his men into the stores and “joy houses” in Singapore and Hong Kong to get contributions. The Rev. George N. Gilligan, a Catholic priest who ran a mission for visiting sailors in Hong Kong, was appalled and complained, terming the effort “polite blackmail” of Hong Kong merchants and wanted it stopped.

Though Adm. Arleigh Burke, the chief of naval operations, and other flag officers thought Smedberg was going too far out on the limb this time, they stood on the sidelines. “They let me get away with it, because none of them really thought I was going to make it,” said the superintendent. “But they all wanted the stadium.”

The Seventh Fleet eked out a victory, but both Fleets earned their gates.

In all, Fluckey cashed out 300 memorial plaques, numerous gates, walls, and arches and more than 8,000 memorial chairs. The submarine fleet donated $10,000. Veterans of Fluckey's old boat, the

Barb

, pledged $1,000.

In the end, “the drive,” as Fluckey and Admiral Smedberg termed it, easily eclipsed the goal. The fund went over the top in July 1958. Captain Fluckey was ecstatic, announcing to the news media that the Navy had not used the services of professional fundraisers. “Ninety-eight cents out of every dollar is going into construction,” he declared.

Four other fundraising drives in 1957â58 for the USS

Enterprise,

the

Constellation,

the

Arizona Memorial

, and the Air Force Academy Stadium failed.

Navy Secretary Gates was amazed the academy's effort succeeded. “Smeddy, I didn't think you could do it. I don't know yet how you did it,” he said to the superintendent. Replied Smedberg, “It was all due to Gene Fluckey. It wasn't due to me, it was due to this dynamic Fluckey.”

Construction of the Navy-Marine Corps Memorial Stadium began in the summer of 1957 and the stadium was dedicated on 26 September 1959. That day, the Midshipmen pounded William & Mary on the gridiron, 29-2. Though the team finished the season 5-4-1, Joe Bellino emerged as a star running back under first-year coach Wayne Hardin. The next year the team posted a 9-1 regular season record, with Bellino winning the coveted Heisman Trophy as the best halfback in college football. The team appeared in the Orange Bowl, losing narrowly to Missouri, 21-14.

For Gene Fluckey, the dedication of the stadium seemed somewhat prophetic. In a letter to Admiral Nimitz in 1947 updating him on the Merit Badge quest, Fluckey made reference to the Navy's growing inability to draw recruits. “Would you inform Admiral Denfeld [Nimitz's replacement as chief of Naval Operations] that the personnel situation is scraping the bottom of the barrel to such an extent that he had better convert the naval Air Arm into a sky-writing outfit for recruiting purposes. Can't you visualize the blue skies over a football stadium plastered with âJoin the Navy'?”

Twelve years later Gene Fluckey made that a possibility in Annapolis.

NORFOLKâA small task force of three Navy ships slipped away from Norfolk piers Tuesday on a mission which will have far reaching implications in United States relations with newly emerging countries in Africa. The mission of the force, under the direction of Rear Adm. Eugene B. Fluckey, the youthful commander of Amphibious Group 4, is to quietly extend the hand of friendship of the Navy and the United States to the peoples of the African continent. . . . Fluckey, who has been called on to direct the operation, is a much decorated hero of World War II.

The Virginian-Pilot,

20 April 1961

It was called Solant Amity II (short for South Atlantic Friendship) and for Gene Fluckey the voyage to Africa would mark the beginning of a decade of remarkable events for him as a flag officer in the Navy. The mission was to give the newly elevated rear admiral a chance to flex his leadership skills in an area of the world fast becoming a front line in the Cold War.

Gail Bove, Gene Fluckey's granddaughter, as a teenager in the 1970s.

Courtesy Fluckey family

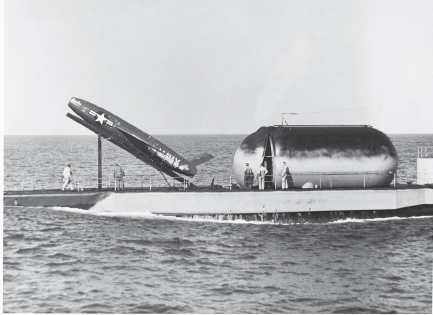

A prototype

Regulus

missile is poised for launch from the deck of a submarine in the mid-1950s. Commander Fluckey pioneered the use of missiles fired from the

Barb

in his last war patrol and conceived the idea of ballistic missile submarines as a deterrent to nuclear war. He was involved in the test program for the

Regulus,

which was the forerunner of

Polaris

and

Triton

missile systems.

Courtesy Fluckey family

Capt. Eugene Fluckey after achieving what others in the Navy thought was impossibleâraising more than $2.2 million to construct the Navy-Marine Corps Memorial Stadium at the Naval Academy in 1959.

Courtesy Fluckey family