The Galloping Ghost (17 page)

Read The Galloping Ghost Online

Authors: Carl P. LaVO

The submarine roars along at flank speed in the Pacific as lookouts keep a steady watch for targets and danger.

Courtesy Don Miller

USS

Barb

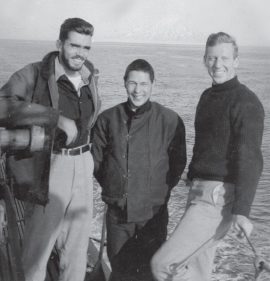

Executive Officer Bob McNitt (

left

) and Skipper Gene Fluckey flank Kitojima “Kito” Sanji, a Japanese prisoner of war rescued from a sinking enemy ship. Sanji later provided crucial intelligence to the success of the submarine's eighth war patrol north of Japan.

Courtesy Bob McNitt

Barb

crewmen line up for rescue duty on storm-tossed South China Sea in 1944.

Courtesy Fluckey family

Lt. Cdr. Eugene Fluckey (

center, front

) and

Barb

crewmen celebrate rescue of Australian and British prisoners on arrival in Saipan. William E. Donnelly, the

Barb

's chief pharmacist's mate, has his arms wrapped around the shoulders of two of the Aussies rescued adrift for six days on the South China Sea.

Courtesy Fluckey family

Sea bird that kept foiling attack on enemy target during

Barb

's ninth war patrol sits atop periscope.

Courtesy Fluckey family

Vice Adm. Charles A. Lockwood Jr. presents Navy Cross to a proud Cdr. Eugene B. Fluckey aboard the

Barb

on 6 December 1944.

U.S. Navy photo

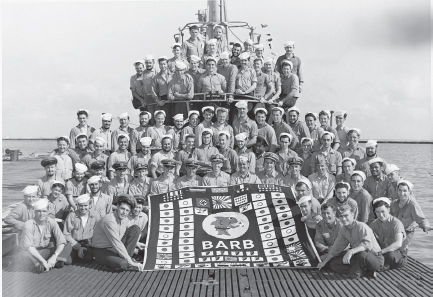

The entire crew of the

Barb

poses with the sub's battle flag after completion of the boat's twelfth war patrol at Midway. Commander Fluckey is in the middle at top of the flag. The submarine sank more enemy tonnage than any other submarine under a single skipper in the Pacific war.

Courtesy Fluckey family

Added McNitt, “I think he may have saved the ship.”

Fluckey, meanwhile, was hopeful for a quick turnaround so the

Barb

could head back into action. That would have to wait for a refit at Pearl Harbor four days later. There Admiral Lockwood wanted to talk to Fluckey. So did the president of the United States.

The phone jangled insistently in Gene Fluckey's room at the Royal Hawaiian. It was 0900. The captain, his officers, and the

Barb

's enlisted men had been ensconced at the four-story luxury hotel on Waikiki Beach for only the second day in two weeks of much deserved R&R, courtesy of the Navy. Now someone was on the line sounding awfully curt.

“Get down in front of the hotel in ten minutes,” demanded the unidentified male caller. “President Roosevelt wants to meet you.”

Fluckey wasn't falling for the prank. “You've been drinking!” he interjected.

“Captain, this is Admiral Lockwood. Be there!”

It was no joke. The president was on his way to meet the skipper. The

Barb

's record of five ships and two trawlers sunk in the Okhotsk Sea had generated quite a buzz. More fantastic were details revealed in the

Barb

's war patrol report being circulated among sub captains: whirlpools hundreds of yards wide that the ship dived through . . . volcanoes spewing ash and fire . . . icebergs and white seals drifting by . . . running battles amid ice floes . . . dense fog that appeared and disappeared in an instant . . . incredible mirages of enemy ships far over the horizon . . . Japanese pilots practicing dogfight maneuvers overhead . . . dramatic attacks . . . a near ramming . . . aerial bombardments . . . a prisoner taken . . .

It seemed the stuff of fiction. Yet every detail was vouched for by crew members. “Gene had a skill in writing patrol reports that gave a vivid picture of what had happened without exaggeration. He didn't need to exaggerate, as the events were always bigger than life,” said McNitt, the

Barb

's executive officer. Lockwood was so enthralled after reading the report that he sent the narrative to Admiral Nimitz, who passed it along to Franklin D. Roosevelt for overnight reading. The president had arrived in Honolulu for a strategy meeting with Nimitz and Army Gen. Douglas MacArthur. After reading the

Barb

report, Roosevelt insisted on meeting the skipper

the next morning. So precisely at 0910 Fluckey joined Lockwood in front of the Royal Hawaiian as the president's limousine rolled to a stop. Lockwood went to the right back door and opened it, helping the polio-afflicted president put his legs out so he could face the skipper, who greeted the commander in chief warmly. Roosevelt introduced Fluckey to Admiral Nimitz, sitting in the middle, and General MacArthur on the far side. Nimitz shook Fluckey's hand while MacArthur gave him a wave. Looking into the face of the Army's Pacific commander, Fluckey flashed back to Washington in 1932, when he watched as a much younger MacArthur ordered “fix bayonets!” and drove World War I veterans out of the District of Columbia and across a bridge into Virginia. The protesters, 15,000 strong, had bivouacked in the so-called Bonus City to demand bonuses Congress had promised eight years earlier but never paid.

Roosevelt and Fluckey chatted briefly. The president was intrigued that the

Barb

had spent only a single day submerged during its fifty-two-day patrol. Fluckey explained his strategy. Waiting in ambush for something to float by in daylight while submerged with three feet of periscope exposed was too limiting. By his estimate, only thirteen square miles of ocean could be scanned. A surface search, on the other hand, allowed the boat to raise the periscope to fifty feet, enabling a view of 206 square miles. “You see more ships and sink more ships,” said the captain with a grin.

“Battle reports like yours let me sleep, confident that peace is inevitable,” the president replied. Turning to Admiral Nimitz, he added, “Chester, I want you to personally see that I am sent a copy of

Barb

's patrol reports whenever Captain Fluckey returns from patrol.” The five men then exchanged salutes before Roosevelt, MacArthur, and Nimitz drove off.

Roosevelt had been so impressed by Fluckey's enthusiasm and the results of his first war patrol that the next day he asked Lockwood if he'd have the skipper rev up the

Barb

's engines and cruise past a landing at Pearl Harbor. The president would be waiting to film the boat from his wheel-chair; he loved making home movies and wanted to take back a memento of the

Barb

.

How do you turn down the president?

At Lockwood's direction, Fluckey assembled his crew and cast off. The

Barb

puttered by the landing as Roosevelt filmed the scene. He wasn't happy. The sub was going too slow. Its battle flag and pennants hung limply. Could Fluckey do it again, but this time faster?

The admiral ordered the skipper to take the

Barb

back out and come back in, this time with a head of steam. This angered the captain since there was a great risk of crashing into a ship moored at the landing. Any damage

to the

Barb

certainly would put a crimp on the upcoming war patrol. Lockwood didn't want to hear it. “Don't worry about it. I'll be responsible.”

Fluckey, furious, took the conn as the sub backed out into the channel for another run. As Roosevelt gave the signal by dropping his hand, the skipper bellowed, “All ahead full!” The

Barb

surged forward, its flags and pennants fluttering wildly to the president's satisfaction. But Lockwood feared the sub was coming in too fast. The admiral cringed. Just when it seemed a crash was inevitable, Fluckey shouted, “All back emergency! Left full rudder!” A whirl of foam erupted as the boat reversed thrust and shuddered violently to a stop, the bow ten yards short of the ship ahead. Roosevelt clapped approval as crewmen secured mooring lines from the

Barb

. Captain Fluckey crossed the bow to greet the president, pushing by Lockwood, who fumed, “Don't you ever do that to me again.” Fluckey snipped back, “Admiral, then don't ask me to endanger my ship again.”

Later, at Lockwood's office, the two shrugged off the incident. The admiral lavished praise on young Fluckey, noting that only five boat captainsâSlade Cutter, Walter Griffith, Richard O'Kane, Charles Kirkpatrick, and Thomas Klakringâhad equaled his record of five ships sunk on a single patrol. He asked if the skipper wanted to lead the

Barb

back to the Okhotsk. Fluckey demurred, preferring an assignment south of Japan on enemy convoy lanes. “Okay,” replied the admiral. “Get ready for wolf packing in the South China Sea. It's hot as a firecracker.”