The Funeral Makers (9 page)

Read The Funeral Makers Online

Authors: Cathie Pelletier

“And the Lord God caused a deep sleep to fall upon Adam, and he slept: and he took one of his ribs, and closed up the flesh instead thereof; And the rib which the Lord God had taken from man, made he a woman, and brought her unto the man.”

âGenesis 2:21â22, King James

All night she lay in bed and listened to the crickets, listened to each car that passed on the dark road outside, longing to hear one turn into the yard, to hear Ed slam the door, and then his footsteps downstairs. But each car went on its way, lost in red taillights around the turn. Looking out at the moon, Sicily noticed streaks on the window and scolded herself for not having them spotless while the Ivys were in town. The next day, she promised herself, she would wash them until they shone. The moon floated higher over Mattagash like a slow-moving balloon broken from its string. The river was quieter than usual, being low for September. A good rain would make it sing again. Frogs were awake in the marsh across the field and Sicily listened to their conversations.

“I suppose they got family problems, too. Just like us,” she thought. The house was so silent that she was almost certain she could hear her heart pumping sadly in her chest. She looked at the clock on the nightstand. Ed had never before stayed out until two thirty. Had something happened to him? He could have gone off the road somewhere between Mattagash and Watertown and no one would find him until morning. There were places where there were no guardrails to protect anyone from dangerous banks that dropped down to the river. The state should really do something about it. Two young boys from Watertown had driven off the bank by Labbe's potato house and into the river. No one found them until the next day when their frantic families went looking for them.

They had taken their girlfriends home from the drive-in movie. So the sheriff started at the girls' homes in St. Ignace and drove slowly back toward Watertown. That's when the policeman riding with the sheriff spotted a flash of red in the bushes along the river. It was at that terrible turn in the road that had no guard rails and a fifty-foot drop. The red he saw was the car. The two boys were inside. One had died instantly, the driver hours later. He'd been pinned behind the wheel and couldn't move. Sicily thought of his mother, living with the knowledge of her son being only a few miles away and trapped, waiting for someone to find him, or waiting for death, whichever came first. They said that boy's mother woke up at exactly the same time the coroner said he died and she woke her husband and said, “I dreamed of raspberries. Bright red raspberries by the river. We need to go pick them.” And then she turned over and went back to sleep. Two teenage boys taking their dates home. Dead. The state should've put up guardrails after that. It was three o'clock and Sicily's eyes were beginning to feel the lack of sleep. She rubbed them, thinking, “I've got to stay awake.” She crawled out of bed and reached for the extra blanket that lay at the foot. The autumn chill moved to her arms and she felt goose bumps spring up.

“Someone's thinking of me,” she said. Wrapped in the blanket, she pulled her little wicker chair up to the windowsill and looked out again at the night and the narrow road that curved past the Lawler house. At four o'clock she was still waiting, still listening to the night sounds, still hoping one car would shift gears and make the turn into her driveway. But none did.

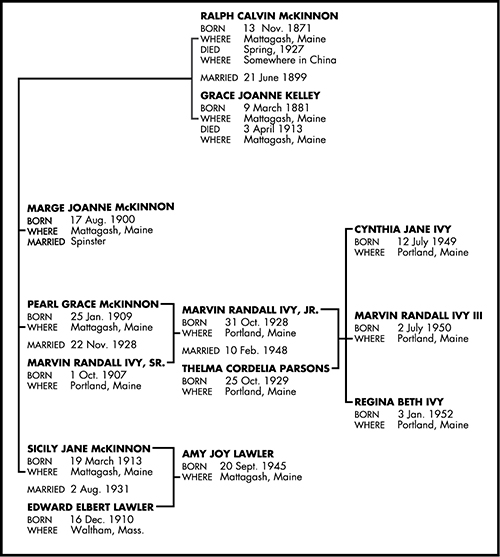

When the Reverend Ralph C. McKinnon took two suits of clothing and a box of Bibles and went off to save the lost souls of China, she had just turned nine years old. She used to think of China as the place where her mother was waiting for her. Once a little girl at school, trying to wrest a doll from Sicily's hands, had lost. So she pointed a small finger at Sicily and shouted, “You killed your mama.” Later, she had asked Marge what that meant and Marge, only in her twenties but with the burden of a family, had run into her bedroom and wept for hours. It was after supper that same evening when Marge told Sicily that their mother never recovered from giving her birth and had gone to God when Sicily was only three weeks old. But the Reverend had talked so of China all those years before he finally packed up and went, that China loomed in her child's mind as a magical place, a place God had moved to in masses, in the forms of sacrificing missionaries. “God is working in China these days,” the Reverend would tell his flock. “God is alive in the rice paddies of China. Our Savior is moving among the heathens of China's vast lands.” It was obvious to Sicily as a child that God was indeed in China. And that meant her mother was in China, too, since everyone, even the Reverend Ralph, had said that she was with God.

After Reverend Ralph gave his three girls a stiff, uncomfortable hug and climbed into the carriage, he never turned once to look back. Marge had taken her old Brownie camera out and snapped a picture of the carriage as it pulled out of the drive and onto the main road. They stood on the front porch and watched him go, the horse's hoofbeats getting fainter, the Reverend's black hat becoming smaller and smaller until it was the size of a period at the end of a bumpy sentence. Only Sicily waved, waved the entire time, her small arm aching, so sure she was that he'd turn in the carriage and wave one last good-bye. But the small period finally disappeared around the turn and the last picture his daughters took of Reverend Ralph was of his back.

For three years Sicily had watched down the road, expecting him at any moment. She refused to believe the few letters he sent home saying his life was in China and that he would never see his homeland again. There was no love in his letters. Each began with “Dear Daughters” and ended with “Hoping God Keeps You Safe in His Bosom.” Sicily often wondered if he'd forgotten their names. Each Sunday Marge gathered them together in the parlor and they wrote him letters. Sicily mentioned each of their names as often as she could, to help him remember. But his letters never referred to his daughters individually. And every day she would find herself staring down the bleak road, expecting to see the Reverend round the bend driving six white horses, her mother sitting like Lazarus beside him, finally rescued from faraway China and brought home to the living and into her daughters' empty arms.

At three thirty Sicily considered phoning the sheriff. All that stopped her was the thought of the gossip that would spread across Mattagash if Ed's car was discovered behind the Watertown Hotel or some other motel, and if he himself was found, not dead in the river, but in some woman's arms, very much alive. Sicily didn't allow herself to think about the other women, although she was certain they existed. Ed had not touched her in years, which relieved her. But she was sure he would take his actions far enough away from Mattagash that she and Amy Joy would be safe from the tongues. Ed would look out for his family. He was a decent man in that respect. She was certain of it. At four fifteen, she was no longer certain of anything. Downstairs in the kitchen she made coffee and tried to work on a crossword puzzle from the

Bangor

Daily

Times

. She gave up on the second clue and read the front page instead. But the black words ran into each other. The obituary page held no entertainment for her. She was too frightened to look at the names, afraid one might be Edward Lawler, as if the world, or God, were playing a nasty joke on her, having taken Ed away without telling her. “The wife is always the last to know,” she remembered Lucy Matlock saying about a woman in Mattagash whose husband had been sneaking into the new schoolteacher's house after dark.

At five o'clock, she stretched out on the sofa in the living room, her sweater spread over her arms, and lay there waiting. Her physical body was giving out, her eyes hurt, a small and sharp pain had begun at the base of her neck. She fought off sleep as long as she could, but finally the eyelids dropped like shades and images old and new bumped together and took their places in her subconscious. There was a bright red car shining from the bushes along the river and she walked forever, then ran as hard as she could to get to it, but it kept moving from her. When she finally grasped the door handle in her hand and opened the door, expecting to see the crushed bodies of two young boys, she found instead the Reverend Ralph behind the wheel and Ed in the passenger seat, both alive, both laughing.

“We're driving to China,” Ed told her, and her hand let go as the car drove out onto the water, as weightless as Jesus, and floated down the river until it was out of sight.

She was left behind shouting, “Come back! Come back!”

When Ed turned the doorknob softly and put one foot inside the house, Sicily heard it in her sleep and dreamed it was the Reverend Ralph come home with her mother. She sat up on the sofa, the warm autumn sun already established throughout the house. She sat up and said, “Mama?”

“I figured that marriage wouldn't last when the little man and woman on the top of their wedding cake got into a fight.”

âMarge McKinnon, About Newlyweds, 1955

From his perch atop the steep, tree-lined ridge that followed the river, Marvin Randall “Randy” Ivy III lay flat on his stomach and peered down on his sister Cynthia, who was comfortably sprawled on a blanket beside the camper. In her hands was her doll Ginger, whose hair had just been brushed vigorously one hundred times and who was being changed from pajamas to swimsuit to evening gown by a dissatisfied Cynthia. She was a fussy mother, already having inherited the role from Thelma, who in turn had come from a long line of nitpickers. Randy sucked in his breath and, silent as a snake, slid along on his belly until he was directly behind his unsuspecting sister. Still concealed by the bushes along the shore, he lay in wait.

“If you don't learn to hang up your clothes, young lady, you won't get any new ones.” Cynthia was warning the indifferent Ginger, whose stiff legs, movable at the crotch, were being made to walk across the blanket to an imaginary bedroom.

“Now you just stay there in your room, without any supper, until you've learned a lesson.” Cynthia shook a younger version of Thelma's bony finger at the doll, who stared, unblinking, into the blue sky that covered Mattagash. Cynthia jumped to her feet and went off into the camper to search for the miniature makeup kit that Ginger would need when the punishment had ended.

Seeing the path cleared for an attack, Randy stuck an arm above his head and with one finger straight out fired several shots.

“Bang! Bang! Bang!” he shouted and swooped down on the vulnerable Ginger. Scooping her up by her well-brushed hair, he swung her around above his head as though she were a lasso. The startled Cynthia stepped down from the camper with Ginger's makeup kit just in time to see the body of her favorite doll flung far out into the Mattagash River. Her cries of agony paralleled those of her mother just two days before when Thelma thought her babies were on fire. Cynthia jumped up and down several times, braids flapping from the sides of her head like wings, and her tears seemed endless. Thelma rushed from the camper and Junior, who had been napping in the tent, crawled out rubbing his eyes.

“What in hell was that?” he asked Thelma.

“Sissy!” Thelma shook her oldest child. “Tell Mama what it is! Did you see something?”

Cynthia, who was unable in her agony to speak, simply nodded, mouth wide open, face twisted with grief. She pointed to the river.

“You saw something in the river?” asked her father, who suddenly noticed Randy for the first time at the end of the camper, where he stood kicking ground with his new PF Flyers.

“What did she see, Randy?” he asked.

“I dunno. A sea monster, I suppose.” The PF Flyers went back to work.

“A sea monster? Are you crazy? Listen, baby,” Junior said, trying to take the girl into his arms. “It must've been a log. There's no such thing as a sea monster.”

But Cynthia, who had just been witness to murder, fought him off, kicking the ground until her frustrated parents gave up and waited for her to come around enough to tell her story.

“She gets that from your mother,” Thelma whispered. “Gets into such a tizzy that she's all nerves and can't talk.”

When the pain of loss subsided enough to make speech possible, Cynthia wiped the discharge from her red nose on the sleeve of her sweater. “Randy drowned Ginger,” she said, and went back to sobbing.

“Oh my God!” shouted Junior. “Who's Ginger?!”

“It's her favorite baby doll,” said Thelma. Despite all the television commercials about the Mercury-like ability of the PF Flyers, Junior caught Randy fifty yards from the camper. He dragged him back to camp and stood him up to face his sister. By this time, Cynthia had been fueled by Thelma's coddling and was wailing like a wronged southern belle.

“My baby, my baby,” she wept on her mother's breast.

Marvin Randall “Randy” Ivy III, unable to be sent to his bed until the camper was prepared for bedtime, was sent to the Packard where he was to stay, forever if necessary, until he apologized to his sister and promised to buy her another doll out of his own allowance. This coffer had already been crippled by the promise to purchase a set of toy tableware for Regina Beth, Randy having nailed all twenty-four pieces of the latter to the telephone pole by the bridge. His hammer set had been locked in the trunk of the Packard to further the punishment, and now Randy himself was confined to the isolated cell of the Packard's backseat.

“I don't know what's in that child to make him do what he does,” Thelma said, trying to mop the perpetual flow of Cynthia's nose. “There's no dispositions like that on my side of the family.”

“Will you quit trying to blame someone else because you should have beaten his little ass years ago and didn't? You always pampered that kid, Thelma.” Junior had not yet vented his anger about the Packard incident, and if Thelma pushed him any more, by God, he would.

“You always told me

not

to spank him because he was a boy, and boys shouldn't be spanked. He was your little man, you said. Gonna follow his daddy's footsteps straight into the Ivy Funeral Home.”

Junior's eyes narrowed slightly and Thelma noticed the change. When his eyes narrowed, it was time to retreat.

“Is the doll gone for good?” she asked her husband, who looked down the fast-moving Mattagash River and said, “I suppose.”

This sparked Cynthia again, and only with the solemn promise that they would drive to Watertown the next day and procure a replacement for Ginger could Thelma soothe the little girl.

Junior went back to his nap and dreams of large-breasted choir girls on the calendar in the MALE EMPLOYEES ONLY restroom of the Ivy Funeral Home. Half into sleep, the blast of the Packard's horn assaulted him like the mating call of a frenzied moose. He bounded from the tent, stepping forgetfully on his still sore ankle, just in time to see his prized Packard, with a vengeful Randy at the helm, coast slowly down the incline and into the Mattagash River. The front fender, slamming into a large rock ten feet offshore, stopped the Packard as water swirled up above the tires.

Randy, who had already decided that they could have the rest of his measly allowance to buy the family a new Packard, let up on the horn. As silence crept in over the front seat, he settled down, his father's son, and waited for the enemy on shore to make the next move.