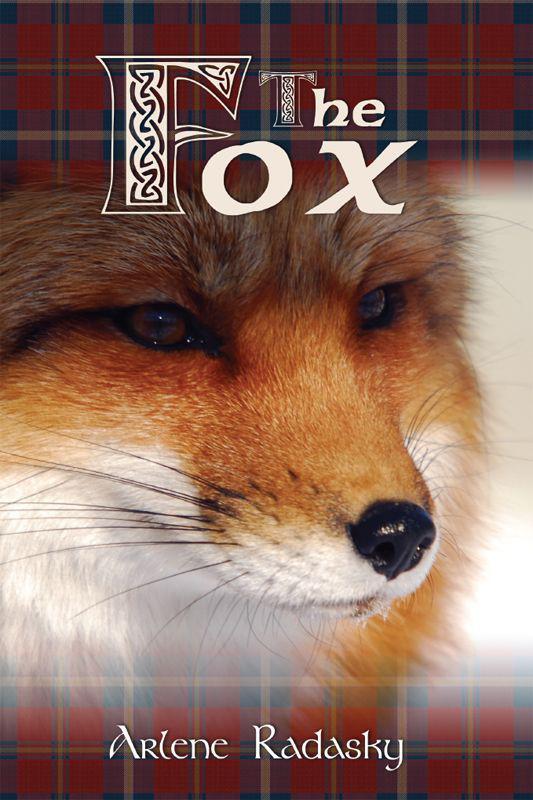

The Fox

Authors: Arlene Radasky

Copyright © 2008 Arlene Radasky

All rights reserved.

ISBN: 1-4392-1175-2

ISBN-13: 9781439211755

eBook ISBN: 978-1-4392-1175-5

Visit

www.booksurge.com

to order additional copies.

Contents

This book would not have been written without all the support and love from my family; my husband Bill; my biggest fan, my mother Lori; Rhonda and my other writer buddies who helped me stay on track.

Thank you.

82 AD N

OVEMBER

I will die when I choose to die.

And as I die, my thoughts will be of Lovern, the Fox, a man who taught me to live, to talk to the gods, and to love. We failed to change the future, and now I beg the goddess Morrigna to allow my daughter a safe journey. I have only time for one more passage dream to tell our story.

Then, I shall die.

72 AD O

CTOBER

Peat smoke darkened the room and firelight struggled to glint off the weapons behind Uncle Beathan, our clan chieftain. I kept my eyes on the weapons so I did not have to look at him. A bronze shield, two spears and two swords – one short, and one long – were balanced against the wall. The sword hilts showed our smith’s interpretations of animals, trees and the spirals of life. If I squinted just right, the bear, Uncle Beathan’s name sign, shrugged its shoulders as if alive. When he was in a better mood than today, he let me touch them. I wished I had worked with my cousin to create this art.

We stood in front of my uncle’s table like thieves as he ate goat cheese and bread, crumbs falling into his beard. My hands were sweating. I held them behind me. I jumped when he spoke. “Jahna, you will marry Harailt.”

He had sent Braden to summon my mother and Harailt, as well as me. Harailt’s father, Cerdic, was there, too. No good ever came from being summoned. Beathan would usually send the girl who did his cooking, Drista, to ask us to join him for family discussions. Drista, a farmer’s daughter honored to be chosen by Beathan to serve at his table, was almost at the marrying age and would leave Beathan’s home soon. He would pick another and another to come to him, until he married.

When our chieftain sent his warrior, Braden, we knew he wanted to discuss important clan matters.

I did not want to be in his lodge that afternoon. Uncle Beathan’s dogs chewed on old pork bones under his table. The smell made my stomach churn.

Mother did not look upset when she glanced down at me. I wondered how we could be mother and daughter. As a small girl, I held up our polished bronze and compared our faces. She told me I was vain. I told her she was beautiful. I felt like a young goat next to her. Mother’s hair was long and straight, the colors of autumn, amber laced with gold and red. Her brother Beathan’s hair was similar. Hers smelled of herbs when she washed it. She wore it loose. Mine was black as a raven’s-wing and never where I wanted it. I wore mine tied back. Her eyes were blue as clear snow water, mine the color of mistletoe leaves with oak splinters. She reached Beathan’s chin, and my head came to his lower chest. Smiles were rare on her solemn face, and I seemed not to know how to be serious. She blended into our family, the village, the clan. I was like none of them. She told me I was like my father, a trader from the south. I wished I had known my father.

Beathan sliced another large piece of cheese and stuffed it into his mouth. My stomach groaned. Chewing, he continued. “However, Cerdic. You do have a rich farm. You will be able to provide your son with sheep and pigs to start his own family. And he will inherit your land one day, goddess willing.” He drank long from his cup of mead.

Cerdic was a small man with arms strong enough to lift one of his sheep out of a ravine and shoulders broad enough to carry lambs. Harailt, like his mother, grew tall, thin and quiet. His shorter father looked up to him but Harailt heeded his father’s wishes.

Blankets and pieces of clothing were strewn all over my uncle’s home. Bridles and parts of his chariot lay on the table in the midst of repair. His hunting dogs laid asleep on his bed, or at his feet, gnawing on the remnants of last night’s dinner. In the gloom of the room, we had to be careful not to trip over whatever was on the floor. My aunt used to straighten after him, but she died two planting seasons ago.

“And Jahna.”

I looked straight at him. Shards of light reflected in his sky blue eyes. I shivered.

“You have seen sixteen harvests,” he said.

I knew I was past the age of marrying. Most girls younger than me were married and had several children hanging onto their skirts. I had foolishly thought Uncle and Mother would let me choose my mate.

“It is time for you to start having babies of your own. You will marry. I will hand-fast you to Harailt at Samhainn, to be blessed by the gods. Now go! I am still hungry. Girl! Mead!” He belched. Drista dashed in, balancing an overflowing mug and more cheese.

Stunned, I hung on to my mother’s arm. As we left his lodge, Uncle Beathan’s words rang in my ears.

“But Mother,” I said. “I have watched Braden for a long time. It was him I hoped to marry. I was waiting for him to ask Uncle for our hand-fasting. Now, I have to marry that—that—farmer.”

“Shush, girl,” my mother said.

I did not care if Harailt heard me. I had known him all my life; we played as children, but I had never thought of marrying him.

I did not know if the tears in my eyes were caused by the sun or disappointment.

I overheard Cerdic as Harailt and his father walked away.

“It is too bad you could not have married Sileas. Her hands are callused from hard work. Her father taught her well. Jahna does not know how to work the land. She has lived with her mother, weaving, and her hands are soft. She will not like to work outside in the fields.”

Yes, I thought, I weave cloth. My hands did not have the grime of the fields on them, but they were still strong hands. Would Harailt only want to marry someone with dirty hands?

“We must do what Beathan decrees,” my mother said. “He is the ceann-cinnidh.”

I glanced over and saw Harailt’s shoulders slump.