The Foreshadowing (15 page)

One day, I tried to talk to Father about becoming a nurse again.

He seemed to listen, but he wouldn’t agree. Then I made the mistake of reminding him that Edgar had said I should have the chance to be a nurse, and that I ought to be given the chance again.

It was a mistake to mention Edgar’s name.

At the end of May it was my birthday.

I am eighteen.

In a few days time it will be Thomas’ birthday. On the first of July he will be nineteen. I wonder where he will be. When he was in Manchester he wrote all the time, but he’s silent now. Of course, it’s harder for him to write than it was for Edgar. Edgar was an officer and had more privileges. Tom is a private, and all we have had from him are two or three postcards that the army issues. They have a list of banal phrases on them, and Tom just crosses out the ones that don’t apply.

Both times he has crossed out all the phrases on the card except the first.

I am quite well.

And he has signed it. That is all we know.

52

I had had no more premonitions since the moment I touched Edgar’s Christmas card, but last night the raven came back to me in a dream.

I heard the beat of its wings, drumming louder and louder. It came right up close to me.

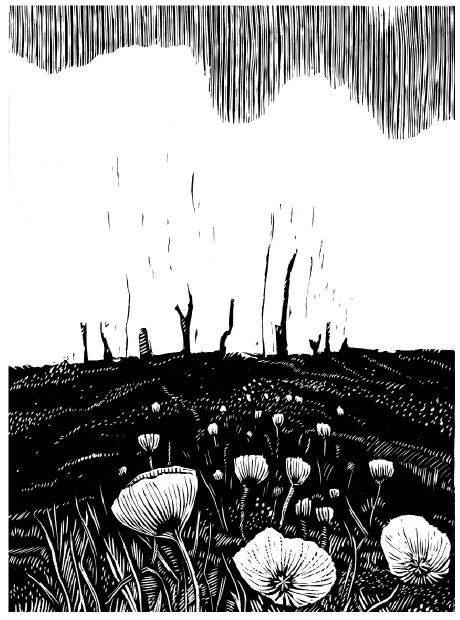

Its wing drifted across in front of my face, so close that I could see the barbs of each feather. The wing swung like a huge black curtain across the stage of a theater, and lifted to reveal a thousand ravens swinging around the treetops of a blighted wood.

The ravens parted, and I saw a gun.

The gun fired, with a violent bang that shook me awake in an instant.

Just before I was pushed out of the dream, I glimpsed one more thing.

The bullet’s target.

Thomas.

It hit him. He’s going to die.

51

At last my time has come.

I know it from the foreshadowing of Thomas’ death.

I don’t know how, but as I lay awake shivering after the dream, I know it hasn’t happened, and that maybe it won’t for some time. It is definitely something that has yet to be.

I don’t know why this is happening to me, or how it does. It feels as if someone is playing games with me, with my life, my destiny. Or with that of my family.

Finally I have the chance to do something with what I have seen.

I know it’s no use to talk to my parents about it. They thought I was living with fantasies before. If I tell them I know Tom is going to die, they’ll probably think I’ve gone mad.

I have to live with this curse now, the curse that is to know the future but never to be believed.

When the sight came to me before—for Clare, for that soldier, for Edgar’s friend, for those patients, for Edgar himself—it did no good.

What was the use? Edgar was dead, but I had no warning; I only knew a few moments before we found out from the telegram.

But this time . . .

This time is different. I’ve been given time to do something with what I have seen. And even if I am wrong, it makes no difference to what I’ve decided.

There’s a big offensive due to start soon; the papers have been full of it. The British and French armies have been gearing up for something massive for months, or so we’re led to believe. If that’s true, then many men will die, but Tom isn’t going to be one of them, because I’m going to stop it.

I’ve planned it all.

Although Father has kept me from the hospital, on several occasions I’ve bumped into nurses I know. We’ve chatted, and they’ve told me about the comings and goings. Lots of young girls have been volunteering to go to France as Red Cross nurses. The hospitals there are desperate for them.

I know where they sail from, and to, and where they go next. The boats leave almost all the time from Folkestone. Dover’s too dangerous, so they sail from Folkestone, a bit farther down the coast. From there, the nurses head to Boulogne, or to Rouen.

And tomorrow, there’s going to be one more nurse joining them.

I don’t know where Tom’s battalion is, but they’re somewhere in Flanders, and once I’m there, it shouldn’t be too hard to find out where.

Then I’m going to bring him home, and stop his death ever having the chance to happen.

If it’s true that I lost my family, and that they lost their faith in me, then this is my chance to mend it all. I want to heal the rift between us, make everything all right again. If I save Tom, then maybe they’ll understand me at last, and I will get them back.

I will save Tom.

It’s my only hope. I must do it.

I must.

PART TWO

50

I’ve been in France for nearly a week, and this is the first chance I’ve had to stop and think.

A week, but it feels like a year, so much has happened.

When I was on the ship, I thought vaguely that I would keep a diary of my journey in France, but I see what a ridiculous idea that was. There wouldn’t have been time, and one week’s experience of the real nature of the war is enough to make me want to forget everything I’ve seen, not make a permanent record of it.

It’s Saturday morning, and I’m sitting in the canteen. All around me are the noises of the rest station, and the sound of trains. I can scarcely believe I’m here, in France. Soon I’ll be moved to work in No. 13 Stationary Hospital, based in huts up on the cliffs, but I’m being given two weeks’ experience in the rest station first. They say it will give me a taste of what I’m likely to encounter. I couldn’t tell them, of course, that I don’t intend to stay that long. As soon as I can find out where Tom is, I’ll be moving on.

The rest station is part of the railway station, converted from rooms along the platform into a suite for ambulance work. We have a surgery and dispensary, a storeroom, and a staff room. We cook outside on large portable boilers.

The reason the rest station is here is because the wounded men roll right into our hands, in trains that have come down from close to the front line. We’re the first port of call. We give the men something to eat and drink, clean them up and maybe dress their wounds. Then on they go, to hospital in Rouen, or a convalescent camp in Havre. If they’re lucky, they might be heading for a ship home.

There’s another thing that can happen. They can die in the rest station, and be taken away to be buried.

It’s an incredible place, full of people throughout the day and night, full of noise and activity. All around, people are speaking English, which surprised me at first, but there are very few Frenchmen here. This place seems to belong to the British Army now, and the few remaining Frenchmen are either very old, or young boys. The rest are away. Fighting. Those who are here work as orderlies and porters, like the old man who runs the platform. He’s in charge of his own little army, composed mostly of boys, and they work continuously, and efficiently. The station is now a station and hospital combined, and runs very smoothly, from what I’ve seen. There’s even a tiny track on the platform itself along which runs a small wooden truck, to move supplies and medicine from one end of the platform to the other. All day long the Frenchman shouts at his boys, who scurry about on the truck, taking rides and fooling about when they think no one’s looking.

I left Brighton last Monday. That was the twenty-sixth, but first I had to prepare my escape.

49

Escape it was. I knew there was no way to tell my parents what I was going to do. All I could do was post a letter before I left Brighton. It will scandalize them, and their acquaintances, when they discover their daughter has vanished, but I can’t help that, either. This is a difficult world now.

On the Sunday before I left, I had to undertake the first part of my plan. A small mission without which none of what I have achieved so far would have been possible.

It was early evening. It was warm, though not bright, but Mother didn’t bat an eye when I said I was going out for a short walk.

“Take a coat,” she called from the kitchen. “It looks like it might rain later.”

That was all she said, but how was she to know of the nervous beat of my blood?

“I’ve got one,” I said.

I walked out of the house and turned down to the seafront, but soon doubled back by turning up Montpelier Road. There, I was lost in the throng of people taking the evening air. I made my way to the hospital.

I carried my coat over my arm; hidden underneath it I had a canvas bag, neatly folded.

Though my heart was racing, I knew that my best chance of success would be to act as relaxed as possible, to project an air of confidence. So as I walked through the doors I simply nodded at the lady on the reception desk. I knew her by sight, and she knew who I was.