The Flatey Enigma (24 page)

Authors: Viktor Arnar Ingolfsson

I

t was almost five in the morning when Grímur and Kjartan clambered down the debarkation bridge on the side of the coast guard ship. Thormódur Krákur had come on board with Grímur after midnight and told the policemen his story. First orally, twice, and then he was asked to describe the events in writing and to sign his statement in the presence of witnesses. The policemen were very suspicious. They couldn’t imagine how anyone could commit such an atrocity on the mere basis of a dream. Finally, Thormódur Krákur was allowed to go home for the night. Inspector Lúkas went with him to confiscate the slaughtering knife. The matter was then to be investigated in greater detail in the morning, when the well and broken lid would be examined. Thórólfur reluctantly agreed to release Kjartan from custody since he was lying awake in his cabin. Jóhanna, on the other hand, was to remain in custody. The case of the Danish professor still loomed over her.

The district officer and the magistrate’s envoy both walked off the pier in silence. The morning sun had risen in the east and was beginning to draw long shadows. An icy nocturnal breeze played on their cheeks, and ice crystals glistened on the pier. Temperatures had dropped to freezing point in the heart of the night.

Some seagulls that had spent the night on the edge of the jetty silently scattered into the sky, disturbed by the men’s approach. An ewe with two lambs lay by the corner of the fish factory and obstinately stood up when they almost stepped on them. Kjartan gazed at the lambs running up the slope toward Ystakot. There were two huts at the end of the shore, and he thought he could make out someone peeping at him from behind one of them. He halted and tapped Grímur’s arm without saying anything. The little head popped out again and now realized it had been spotted and decided to recoil. The small human figure swiftly headed up the slope toward Ystakot.

“Isn’t that little Nonni?” Grímur said. “What’s he doing up so early?”

“Or late,” said Kjartan.

Grímur glanced back at the boats anchored at the pier. “His father’s boat isn’t back yet. Could they still be out at sea and the boy alone at home?”

“Maybe it’s not all as it seems,” Kjartan said softly.

They walked up the slope after the boy. When they reached the croft, they saw the boy in the doorway but then vanishing inside.

Grímur called through the door: “Nonni, come out and talk to us, my friend. We want to help you if there’s something wrong.”

There was no answer, so Grímur stooped to step into the dark cottage. Kjartan followed. They first came into a small, smelly, dirty kitchen. Beyond that there was a small bedroom with four beds, two on either side. Daylight filtered through a small window at the top of the gable, and a half-full potty lay on the floor. Kjartan felt nauseous, turned around, and rushed outside to deeply inhale the clear morning air several times.

“Nonni, my friend,” Grímur called inside. “We only want to ask you about your dad and your grandpa. Have they been away for long?”

Some noise was heard from within, and soon the district officer reappeared with the boy by his side.

“The boy was all alone in there,” Grímur said to Kjartan.

The boy stood beside them, downcast.

“Are your dad and grandpa at sea?” Grímur asked.

“Yeah, but they’ve been gone such a long time,” the boy answered. “They left really early this morning.”

“You mean yesterday morning. Did you get any sleep last night?”

“No, I was waiting for them all day.”

“Where did they go?”

“Out to Ketilsey to pull in the seal net and check on the eiderdown. They weren’t going to be gone this long.”

“Maybe the engine broke down. I’ll go out looking for them. I’m sure they’re in no danger. The weather’s so good. Why didn’t you go with them?”

“I wasn’t allowed to. Dad was punishing me for taking a crap on the island last time, and then I sneaked out of church during the mass on Sunday and he saw me.”

Kjartan had an idea and gently asked him, “Do you have a camera, Nonni?”

The boy looked at him in surprise but didn’t answer.

Kjartan repeated his question: “Don’t you have a camera, my friend?”

Nonni was about to say something, but the words got stuck in his throat.

“I think you have a camera and maybe also some nice binoculars,” said Kjartan.

“How do you know?” said the boy.

“Can I see them?” Kjartan asked.

The boy looked at them with trepidation but then walked away from the croft. Grímur and Kjartan followed him. Nonni walked past the potato patch toward a shed built into the earth of the slope. He entered it through a low doorway and swiftly returned, holding a small bag.

“The foreigner left this bag in the boat when Granddad took him to Stykkishólmur,” he said. “I found it myself and kept it.”

Kjartan took the bag and examined it. Inside it he found a camera, pair of binoculars, a toiletries bag, and underwear that had grown musty from damp storage.

“The camera’s broken,” said the boy. “I’ve tried everything you’re supposed to do, but there’s no picture in the box.”

“Tell us about when your grandpa took the foreigner out,” said Kjartan.

The boy looked up and said, “Dad went to the mainland with the mail boat to get Mom. Me and Grandpa went down when the boat was coming back to grab the ropes. We were then going to go out in the strait to fish some small cod for dinner.”

He grew silent and stared at his treasures. He was trembling from the cold and fatigue.

“What happened then?” Grímur asked.

“We were still on the pier when everyone else had left, and we were going to go out on our boat,

Raven

. Then the foreigner came running over and calling. He was far too late because the mail boat had left ages ago. Then he ordered Grandpa to take him to Stykkishólmur, but it was really difficult to understand him.”

“Did your grandpa agree to sail with him?” Grímur asked.

“Yeah, the man showed us the loads of money he was going to give us when they got to Stykkishólmur.”

“So they went then?”

“Yeah, but the foreigner didn’t want me to come along.”

“Was your grandpa away for long?”

“Yeah, he didn’t come back until the next day. The motor was completely out of fuel, so he came in using the sail when the southern winds started blowing. Grandpa then went to sleep, but I found the bag in the boat and hid it. I would’ve given it back to the foreigner, but he never came back to ask for it.”

“Didn’t your dad know about this?”

“No. He was so angry when he got back from the mainland because Mom wouldn’t come back with him from her roadworks job. He complained about everything and got really mad when he saw the boat was out of fuel. Grandpa couldn’t remember anything about his trip with the foreigner, and I didn’t dare to tell Dad about it. Grandpa has started to forget so many things. I think the foreigner also forgot to pay him the way he’d promised because Grandpa didn’t have any money on him when he got home. I peeped into his pockets when he was asleep.”

“But what about that man from Reykjavik, the reporter? Did he know you were keeping the bag?” Kjartan asked.

Nonni averted his gaze. “Yeah, when I sneaked out of mass, I went home to have a little look through the binoculars. Normally I hardly ever dare to use it because no one’s allowed to see me. I was sure that District Officer Grímur would take it away from me if anyone saw me.”

The boy looked shamefacedly at the district officer.

“Did the reporter see you?” Kjartan asked.

“Yeah, I thought that everyone was still in the church, but then he was suddenly there standing beside me.”

“What did he say to you?”

“He asked me if I owned the binoculars. Then he looked into the bag and saw the little books. Then he asked me if Dad had taken the foreigner to Stykkishólmur. I told him that Grandpa had, but he’d run out of fuel. Then he asked me if he could keep the little books if he promised not to tell anyone about the binoculars and the camera. I said yes, if he wouldn’t tell anyone. He promised and said that then I wasn’t to tell anyone either.”

The boy started whimpering. “And now the reporter is dead and I’m breaking my promise.”

“Do you remember the dead man you saw in Ketilsey?” Kjartan asked.

“Yeah,” the boy answered.

“Had you seen him before?”

“No, I don’t think so. You couldn’t see his face.”

Grímur had listened to the whole story in silence and now spoke: “Right, my friend. Let’s go to my house, Nonni, and we’ll get my Imba out of bed. She’ll give you some milk and something good to eat. Then maybe you’ll get a slice of cake and go to bed. Me and Kjartan here will go looking for your dad and grandpa.”

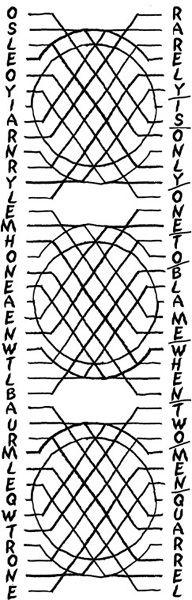

Question forty: The final question has now been reached. It is the key to all the other answers and goes as follows: “Who spoke the wisest?” The answers can vary greatly, according to personal taste and wisdom. There are many wise sayings in this book, but the key here is composed of the following letters:

O S L E O Y I A R N R Y L

E M H O N E A E N W T L B

A U R M L E Q W T R O N E

“My father went through the entire book, page by page, trying out all the sentences that felt reasonably sensible to him and contained some ounce of wisdom. He played around with them, rearranging the letters to see whether they could make up a complete sentence. The spelling was supposed to be in line with what was used in the latter half of the nineteenth century, as far as he knew, and the sentence had to contain exactly thirty-nine letters. He created little tables with these letters and shuffled them over and over again, but still couldn’t find the text to unlock the riddle, and he eventually gave up. Many weeks later, he started thinking about the enigma again. He realized something else was needed to find the right key sentence. Some letters appeared more than once in the rows of key letters, and it was impossible to say how the rows were connected. There had to be some other way of decoding the answer. Then he focused his attention on the drawing that accompanied the clues and had come to be known as the magic rune. Personally, he didn’t believe in that kind of stuff, but he was sure that the author had placed the picture beside the riddle for a reason. He noted that on each side of the picture there were thirteen lines that crossed the picture and reemerged on the other side of it in a different place. Thirteen multiplied by three is thirty-nine, which is the number of letters in the key. He drew a copy of the picture, reproducing it three times in a vertical row. Then he wrote out the key letters downwards in the vertical column and moved them across to the other side of the grid, following each line. The following sentence emerged: ‘Rarely is only one to blame when two men quarrel.’ This is the second part of a sentence that reads as follows and can be considered wise: ‘Remember, though, that rarely is only one to blame when two men quarrel.’ It’s a line from the old saga of Hákon. My father was so fervent in his quest that he overdid it that night. He was extremely ill when I found him in the library, but I had never seen him in such ecstasy. Now all he needed to do was to go over his answers to the thirty-nine questions and see whether they formed the end of the key poem. It should only have taken him part of the day, but he was too ill now and never got out of the house again. He knew he could only do this by strictly abiding by the rules. A short while later Gaston Lund arrived on his fateful visit. My father told him how the ‘magic rune’ was to be used to unlock the solution to the riddle and fortieth question. Lund got very excited about it and was lent the library key to rush up there and try out his answers. But he ran out of time. He didn’t manage to finish the test and later probably missed the mail boat. What happened next is difficult to imagine.”

“My father spent the whole winter trying to muster up enough energy to return to the library and try out his solution. I often offered to do it for him, but he didn’t want me to. He wanted to see the solution appear before his own eyes. Then finally, yesterday, he asked me to go up and try out his solution. He felt death was approaching and wanted to hear the end of the poem before he passed away. I was going to ask Ingibjörg to watch over him and sent for her, but he lost consciousness as I was waiting for her to arrive. He steadily deteriorated during the day and died that evening. He’d solved the code but never knew if he’d found the right solution to the entire enigma. But now we’ll see what happens.”

Jóhanna wrote down the thirty-nine letters in a single column, following her father’s diagram, and numbered them at the same time. Then, starting on each letter, she followed each line across the grid to where it ended on the other side of the picture and wrote the letter out again. Wherever Björn Snorri and Gaston Lund’s answers differed, she wrote down both possibilities. Then she scrutinized the solution for a moment. She crossed out three letters in her father’s answers and three letters in Gaston Lund’s and inserted dashes between the words. She said, “The solution is: