The First 90 Days (9 page)

Authors: Michael Watkins

Tags: #Success in business, #Business & Economics, #Decision-Making & Problem Solving, #Management, #Leadership, #Executive ability, #Structural Adjustment, #Strategic planning

position, a fundamental challenge for new leaders. ?Promoting yourself ?

does not mean self-serving grandstanding or hiring a PR firm. It means preparing yourself mentally to move into your new role by letting go of the past and embracing the imperatives of the new situation to give yourself a running start. This can be hard work, but it is essential that you do it. All too often, promising managers get promoted but fail to promote themselves by undertaking the necessary change in perspective.

A related mistake is to believe that you will be successful in your new job by continuing to do what you did in your previous job, only more so. “They put me in the job because of my skills and accomplishments,” the reasoning goes.

“So that must be what they expect me to do here.” This thinking is destructive because doing what you know how to do and avoiding what you don’t can appear to work, at least for a while. You can exist in a state of denial, believing that because you are being productive and efficient, you are being effective. You may keep on believing this until the moment the walls come crashing down around you.

No one is immune to this trap, not even accomplished senior executives. Consider the experience of Douglas Ivester at Coca-Cola. Ivester was promoted to CEO in 1997 after the sudden death of his predecessor, the highly praised

[1]

Roberto Goizueta, who had led Coke since 1981.

In 1999, after a string of missteps that had eroded the confidence

of Coke’s board of directors, Ivester resigned.

To outside observers, Ivester had appeared to be the perfect candidate for the job. “The real challenge [for Coca-Cola],” wrote one PaineWebber analyst, “is not becoming a casualty of their own success. And I think with the

[2]

current lineup at Coke, starting with Doug Ivester, they’re not too likely to become complacent.”

Fortune

dubbed him

[3]

the “prototype boss for the 21st century.”

An accountant by training, Ivester had spent nearly twenty years rising through the ranks to become Coke’s COO and Goizueta’s right-hand man. Named Coke’s CFO in 1985, at age thirty-seven, he quickly made his mark by

orchestrating the successful 1986 spin-off of the company’s bottling operations, Coca-Cola Enterprises. He also succeeded as president of European operations, his first operating role, and oversaw the company’s expansion into Eastern Europe in 1989. Ivester was named president of Coke USA one year later and became president and COO of the company in 1994.

But Ivester was unable to make the leap from COO to CEO. He refused to name a new COO, even when strongly pressed to do so by Coke’s board of directors. Instead, he continued to act as a “super-COO” and maintained daily contact with the sixteen people who reported to him. His extraordinary attention to detail, which had been such a virtue in finance and operations, proved to be a hindrance in this new position. Ivester could not free himself from day-to-day operations enough to take on the strategic, visionary, and statesmanlike roles of an effective CEO.

The result was a series of missteps, none fatal on its own, that cumulatively sapped Ivester’s credibility. His ham-handed treatment of European regulators contributed to Coke’s failure to acquire Orangina in France and drastically reduced the value of its acquisition of Cadbury Schweppes’s brands. He was also widely seen as having mishandled a crisis in 1999 involving contamination of Coke bottled in Belgium by not visibly taking charge. He alienated other potential allies by failing to respond effectively to a festering racial discrimination suit in Coke’s Atlanta headquarters, and by applying too much pressure to Coke’s already stretched bottlers regarding concentrate pricing and inventories. By the end, Ivester had few friends.

Suggesting that Ivester’s failure was the result of a fatal character flaw, the

Wall Street Journal

mused, “The job of running a giant company like Coca-Cola Co. is akin to conducting an orchestra, but M. Douglas Ivester, it seems, had

[4]

a tin ear. . . . [He] knew the math, but not the music required to run the world’s leading marketing organization.”

The root causes of Ivester’s failure, however, lay less in what he could not do (or learn to do) than in what he could not let go of. An impressive career came to a deeply disappointing, even tragic, conclusion because he persisted in concentrating on what he felt most competent doing. Was his failure inevitable? Probably not. Was it likely given his approach to the transition from COO to CEO? Absolutely.

[1]Ivester’s story is chronicled in M. Watkins, C. Knoop, and C. Reavis, “The Coca-Cola Co. (A): The Rise and Fall of M. Douglas Ivester,” Case 9-800-355 (Boston: Harvard Business School, 2000).

[2]C. Mitchell, “Challenges Await Coca-Cola’s New Leader,”

Atlanta Journal and Constitution,

27 October 1997.

[3] P. Sellars, “Where Coke Goes from Here,”

Fortune,

13 October 1997.

[4] “Clumsy Handling of Many Problems Cost Ivester Coca-Cola Board’s Favor,”

Wall Street Journal,

17 December 1999.

This document was created by an unregistered ChmMagic, please go to http://www.bisenter.com to register it. Thanks

.

Promoting Yourself

How can you avoid this trap? How can you be sure to embrace the challenges of your new position? This section provides some basic principles for mentally getting ready for your new position.

Establish a Clear Breakpoint

The move from one position to another usually happens in a blur. You rarely get much notice before being thrust into a new job. A lucky new leader gets a couple of weeks, but more often the move is measured in days. You get caught up in a scramble to finish up in your old job even as you try to wrap your arms around the new one. Even worse, you may be pressured to perform both jobs until your previous position is filled, making the line of demarcation even fuzzier.

Because you may not get a clean transition in terms of job responsibilities, it is essential to discipline yourself to make the transition mentally. Pick a specific time, such as a weekend, and use it to imagine yourself being promoted.

Consciously think of letting go of the old job and embracing the new one. Think hard about the differences between the two and in what ways you have to think and act differently. Take the time to celebrate your move, even informally, with family and friends. Use the time to touch base with your informal advisers and counselors and to ask for some quick advice. The bottom line: Do whatever it takes to get into the transition state of mind.

Hit the Ground Running

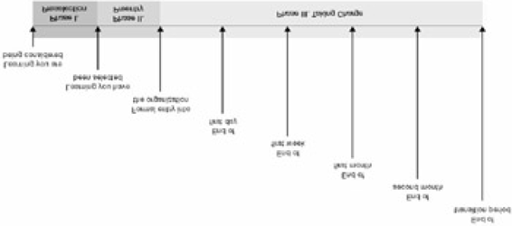

Your transition begins the moment you learn you are being considered for a new job (see figure 1-1

). It ends roughly 90 days after you begin the job. By this point, key people in the organization—your bosses, peers, and direct reports—expect you to be getting some traction.

Figure 1-1:

Key Transition Milestones

A three-month time frame is not a hard and fast rule; it depends on what type of situation you are entering.

Regardless, you should use the 90-day mark as a key milestone for planning purposes. It will help you confront the need to operate in a compressed time frame. If you are lucky, you may get a month or more of lead time between learning you are being considered and sitting in the chair. Use that time to begin educating yourself about your organization.