The First 90 Days (29 page)

Authors: Michael Watkins

Tags: #Success in business, #Business & Economics, #Decision-Making & Problem Solving, #Management, #Leadership, #Executive ability, #Structural Adjustment, #Strategic planning

This document was created by an unregistered ChmMagic, please go to http://www.bisenter.com to register it. Thanks.

Leading Change

As you work out where to get your early wins, think about how you are going to make change happen in your organization.

Planned Change Versus Collective Learning

Once you have identified the most important problems or issues you need to address, the next step is to decide whether to engage, as my colleague Amy Edmondson has noted, in planthen-implement change or promotion of

[5]

collective learning.

The straightforward plan-then-implement approach to change works well when you are sure that you have the following key supporting planks in place:

1.

Awareness:

A critical mass of people are aware of the need for change.

2.

Diagnosis:

You know what needs to be changed and why.

3.

Vision:

You have a compelling vision and a solid strategy.

4.

Plan:

You have the expertise to put together a detailed plan.

5.

Support:

You have a sufficiently powerful coalition to support implementation.

The plan-then-implement approach to change might work well in turnaround situations, for example, where people accept there is a problem, the fixes are more technical than cultural or political, and people are hungry for a solution.

If any of these five conditions are not met, however, the pure plan-then-implement approach to change can get you in trouble. If you are in a realignment, for example, and people are in denial about the need for change, they are likely to greet your plan with stony silence. You may therefore need to build awareness of the need for change, or sharpen the diagnosis of the problem, or create a compelling vision and strategy, or develop a solid cross-functional implementation plan, or create a coalition in support of change.

To accomplish any of these goals, you would be well advised to focus on setting up a collective learning process, and not on developing and imposing change plans. If many people in the organization are willfully blind to emerging problems, for example, you have to put in place a process to pierce through this veil. Rather than mount a frontal assault on the organization’s defenses, you should engage in something akin to guerrilla warfare, slowly chipping at their resistance and raising their awareness of the need for change.

You can do this by exposing key people to new ways of operating and thinking about the business, such as new data on customer satisfaction and competitive offerings. Or you can do some benchmarking of best-in-class organizations, getting the group to analyze how your best competitors perform. Or you can bring people to envision new approaches to doing things, for example, by scheduling an off-site meeting to brainstorm about key objectives or about improving existing processes.

The key, then, is to figure out which parts of the change process can be best addressed through planning and which are better dealt with through collective learning. Think of a change that you want to make in your new organization.

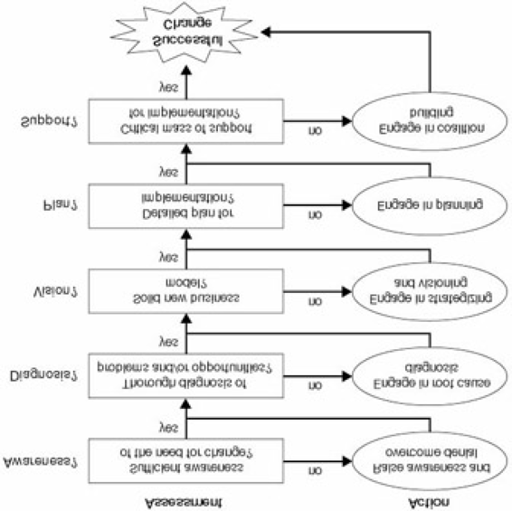

Now use the diagnostic flowchart in figure 4-2

to figure out where collective learning processes are likely to be important to your success.

Figure 4-2:

Diagnostic Framework for Managing Change

Getting Started on Behavior Change

As you plan to get early wins, remember that the means you use are as important as the ends you achieve. The initiatives you put in place to get early wins should do double duty by establishing new standards of behavior. Elena Lee did this when she carefully staffed and coached her project team and then quickly implemented their recommendations.

To change your organization, you will likely have to change its culture. This is a difficult undertaking. Your organization may have well-ingrained bad habits that you want to break. But we know how difficult it is for one person to change habitual patterns in any significant way, never mind a mutually reinforcing collection of people.

Simply blowing up the existing culture and starting over is rarely the right answer. People—and organizations—have limits on the change they can absorb all at once. And organizational cultures invariably have virtues as well as faults; they provide predictability and can be sources of pride. If you send the message that there is nothing good about the existing organization and its culture, you will rob people of a key source of stability in times of change. You also will deprive yourself of a potential wellspring of energy into which you could tap to improve performance.

The key is to identify both the good and bad elements of the existing culture. Elevate and praise the good elements even as you seek to change the bad. These functional aspects of the familiar culture are a bridge that can help carry people from the past to the future.

[5]My colleague Amy Edmondson developed this very useful distinction.