The Firebrand and the First Lady: Portrait of a Friendship: Pauli Murray, Eleanor Roosevelt, and the Struggle for Social Justice (6 page)

Authors: Patricia Bell-Scott

Tags: #Political, #Lgbt, #Biography & Autobiography, #History, #United States, #20th Century

Murray, who knew nothing of ER’s sorrows, studied her surreptitiously. The

first lady was fifty years old and nearly six feet tall. She wore no makeup.

She tied her light brown hair back with a ribbon. Her dress had simple lines. Her shoes were low-heeled and practical.

Murray’s observations corroborated news stories, such as those written by Hickok, detailing the first lady’s resolve to be “

plain, ordinary Mrs. Roosevelt,” despite her new role. She, and not a chauffeur or

Secret Service agent, had driven her party to the camp.

She had raised eyebrows in Washington’s high society when she positioned herself alongside the waitstaff to serve ham sandwiches at an inaugural luncheon, thereby demonstrating a desire to serve others and a preference for informality. She gave a garden party on the grounds of the White House for residents of the

National Training School for Girls, which, in contrast to its name, resembled a prison. It had no teachers or counselors, and the living quarters were “

dark” and “unsanitary.” When ER was told that politicians would be upset if she hosted black and white girls together, she said, “

It may be bad politics, but it’s a thing I would like to do as an individual, so I’m going to do it.”

This was not the first time

Eleanor Roosevelt had acted on her convictions.

Six years before she became first lady, she was arrested and charged with disorderly conduct after she joined three hundred picketers in support of a paper box makers’ strike in New York City.

Now that she was first lady, she would avoid arrest, but she continued to work with union leaders, such as

Rose Schneiderman, and to lobby for fair wages, for better working conditions, and against child

labor.

ER changed the complexion of the White House by hiring only black maids, much to the chagrin of her mother-in-law. The first lady’s dinner guests, a mix of friends, artists, young people, and, sometimes, “

destitute” men she had met in the park, reflected her wish to get to know people from all age groups and walks of life. She was said by one journalist to favor unconventional thinkers and “

people who do things” over “stuffed shirts, fat-heads and very proper people.”

Had her husband not been a candidate for president, she confided to a friend, she would have voted for the socialist

Norman Thomas.

At the suggestion of

Hickok, who would become a lifelong friend, Eleanor Roosevelt set a precedent by holding weekly

press conferences with women reporters.

She invited the public to write to her about their problems, and more than three hundred thousand did just that in her first year as first lady. While she could not help everyone who asked, she responded to each letter or passed it on to someone—a division chief, cabinet secretary, or the president—who could.

ER’s passion for examining issues up close fascinated the public. Indeed, the distances she traveled and the inconveniences she tolerated were unparalleled for a first lady.

She braved the squalor and soot of a

West Virginia mining town to discuss living conditions with black miners.

Mud coated her shoes as she tramped through an army bonus

camp to talk with

World War I veterans about their unpaid pensions. “

An able-bodied man at the pink of condition would have difficulty in keeping up with her when she walks,” noted a reporter for the

Washington Post

. The

Secret Service appropriately code-named her

Rover.

ER was determined that the first camp for women succeed. Given her insistence that Camp Tera be racially inclusive and her practice of counting the number of black residents, ER must have noticed the small brown girl with cropped hair in pants sitting near the social hall. Perhaps because Murray seemed to be reading or because her shyness was so obvious, ER, who normally greeted everyone, simply passed by.

· · ·

AS SOON AS ELEANOR ROOSEVELT LEFT

, Jessie

Mills summoned Murray to the main office and accused her of disrespecting the

first lady by not “

standing at attention.”

Mills, who’d been an ambulance driver in

World War I, had the demeanor of a drill sergeant. Her thick eyeglasses and the dark suit she accented with a narrow tie magnified her overbearing personality. She woke residents at six in the morning with a bugle call and signaled changes in the schedule of activities with a shrill bell. Lights went out at ten with taps. She forbade the staff from fraternizing with residents beyond their official duties.

Mills’s authoritarianism and her accusation offended Murray, for she had made herself as presentable as possible and stayed out of ER’s way. Furthermore, the first lady’s unpretentiousness, Murray insisted, showed that she neither wanted nor needed “

obsequious behavior” from anyone. Mills resented Murray’s assertiveness and soon found an excuse to oust her. During a routine search, Mills came across a copy of

Karl Marx’s

Das Kapital

in Murray’s belongings.

This time, Mills accused Murray of being a

Communist.

Das Kapital

was a required text in a political philosophy course Murray had taken at

Hunter. She had brought it along with a stack of novels and books of poetry.

Intellectually curious and accustomed to reading widely, Murray vehemently denied that she was a Communist. Mills took her possession of Marx’s book as proof otherwise.

Mills often allowed residents to stay until they secured a job or other means of support.

Murray’s

friend Pee Wee, for example, had been at the

camp for nearly eighteen months and would remain there until the facility closed, two years later.

But Mills expelled Murray immediately, partly out of frustration with her rebelliousness and partly out of fear that groups closely watching the camp, such as the

American Legion, would accuse the staff of harboring Communists.

It is also possible that Mills, who would shortly lose her job due to alleged improprieties, was motivated by her disapproval of Murray’s friendship with Peg. That their relationship was close, interracial, and between a camp staffer and resident made it unacceptable to Mills on several counts.

Pauli Murray’s residency at Camp Tera lasted just over three months.

After a five-week hitchhiking trip to Nebraska with Peg, Murray returned to

New York City, homeless and without a job. She never expected to cross paths with Eleanor Roosevelt again.

PART I

TAKING AIM AT THE WHITE HOUSE,

1938–40

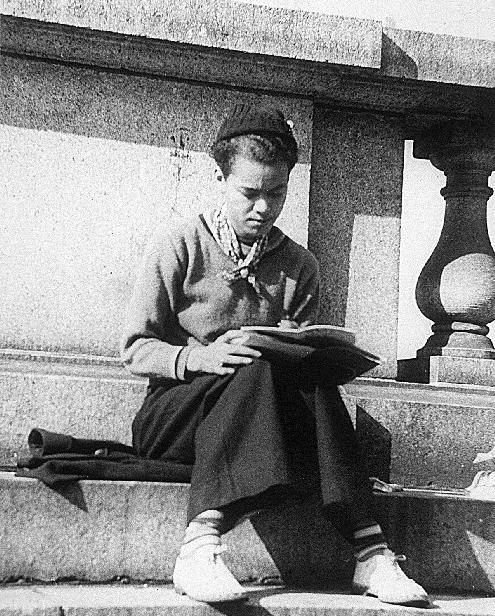

Pauli Murray, here a twenty-seven-year-old WPA teacher, composes a poem on Election Day 1938 on Riverside Drive, New York City. She often marked historical and personally meaningful events by writing poetry and prose.

(The Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University and the Estate of Pauli Murray)

1

“It Is the Problem of My People”

T

he clatter of Pauli Murray’s old

typewriter bounced off the walls of her one-room Harlem apartment on December 6,

1938. Working at breakneck speed, she stopped only to look over a line in her letter or take a drag from her ever-present cigarette. Although she was only five-foot-two and weighed 105 pounds, she hammered the keys with the focus of a prizefighter.

She had been forced to move three times because neighbors found the noise intolerable.

The catalyst for Murray’s current agitation was

Franklin Roosevelt’s speech at the

University of

North Carolina the day before.

It was his

first address since the 1938 midterm elections and the fourth visit to the university by an incumbent president.

The reports of his isolation at his vacation home in

Warm Springs, Georgia, and the arrangements for

radio broadcasts to Europe and Latin America had sparked international interest in his speech.

Thousands lined the motorcade path to UNC in the drenching rain, holding handmade signs and flags, hoping to catch a glimpse of the fifty-six-year-old president in his open car. When it became apparent that there would be no break in the downpour, organizers moved the festivities from Kenan Stadium to the brand-new Woollen Gymnasium. There, in an over-capacity crowd of ten thousand, a man fainted from the swelter. Many people went to other campus buildings to listen to the broadcast. Countless numbers stood outside the gym in the rain. Before FDR spoke, the university band played “Hail to the Chief,” school officials awarded him an honorary doctor of laws degree, and an African American choir sang spirituals.

Under the glare of klieg lights, the warmth of his academic regalia, and the weight of his steel leg braces, the president made his way to the flag-draped platform. He paused often during his twenty-five-minute address for roaring applause, wiping his face with the handkerchief he slipped in and out of his pocket, gripping the lectern to maintain his balance. He praised the university for its “

liberal teaching” and commitment to social progress. He declared his faith in youth and democracy. He urged Americans to embrace “the kind of change” necessary “to meet new social and economic needs.”

Having listened to the broadcast the day before, Murray underlined passages in the speech from the

New York Times

front-page story “Roosevelt Urges Nation to Continue Liberalism.” The “

contradiction” between the president’s rhetoric and her experience of the South made her boil. She would never forget the day a bus driver told her to “

relieve” herself in “an open field” because the public toilets were for whites only. Insulted, she rode in agony for two hours, not knowing if there would be toilet facilities for blacks at the next stop.

Murray wondered if it mattered to the president that the “

liberal institution” that had just granted him an honorary doctorate, and of which he claimed to be a “

proud and happy” alumnus, barred black students from its hallowed halls and confined those blacks who came to hear him to a segregated section. Did he understand the psychological wounds or the economic costs of

segregation? And how could he rationally or morally associate a whites-only admissions policy with liberalism or social progress?

Having applied to UNC’s graduate program in sociology a month before FDR’s visit, Murray aimed to see just how liberal the school was.

· · ·

EXACERBATING MURRAY

’

S FRUSTRATION

with the president was his previous condemnation of

lynching as “

a vile form of collective murder” and his recent silence during a thirty-day Senate filibuster of the

Wagner–Van Nuys bill that would have made lynching a federal offense. After the bill died, FDR proposed that a standing committee of Congress or the attorney general investigate

“lynchings

and incidents of mob violence.”

The black press lashed out against his political maneuvering. The

New York Amsterdam News

condemned him for keeping “

his tongue in his cheek!” The

Chicago Defender

called him “

an artful dodger.” The

Louisiana Weekly

, predicting that blacks would abandon the Democratic Party, declared, “

You’re too late, Mr. President, and what you say is NOTHING.”

Murray understood that FDR’s reticence on anti-lynching legislation was an attempt to placate conservative politicians from the South, where whites lynched blacks with impunity.

Her introduction to politics had begun as a preschooler, reading newspaper headlines to her grandfather Robert

Fitzgerald, a Union army veteran whose injury in the

Civil War cost him his vision in his old age. Robert, originally from Pennsylvania, settled in North Carolina after the war to teach ex-slaves. He had also nurtured his granddaughter’s intellect and her love of African American literature and history. That this year marked the seventy-fifth anniversary of the

Emancipation Proclamation made the president’s inaction even more objectionable to Murray.

Since 1863, more than three thousand blacks had been lynched, and at least seventy of these murders had taken place during FDR’s presidency.

Murray’s indignation was rooted in bone-chilling stories she had heard as a child of racial brutality and the Klansmen who circled her grandfather’s property nightly on horseback, threatening to shut down his school for blacks. Ever brave, Robert had kept “

his musket loaded” and the school door open. Murray had her own stories, too.

When she was six years old and on her way to fetch water from a community well, she and a neighbor came upon a group of blacks gathered around the body of young

John Henry Corniggins, sprawled near a patch of thorny shrubs. Murray saw “

his feet first, the white soles sticking out of the grass and caked with mud, then his scratched brown legs.” His eyes were open. Blood seeped through a bullet hole in his shirt near his heart.

John Henry lay motionless as large green flies wandered over his face and into his mouth. Nearby, a solitary “

buzzard circled.” Murray raced home, trembling in a cold sweat. The word among blacks was that a white man had assumed John Henry was stealing watermelons and shot him. No evidence of theft was found near the boy’s body. No one was arrested for his murder.

Six years later, violence touched Murray’s

family when a white guard at Maryland’s

Hospital for the Negro Insane murdered her father. At the funeral, she could hardly believe that the “

purple” bloated body in the gray casket was her once proud father. She was horrified by the sight of his mangled head, which had been “

split open like a melon” during an autopsy “and sewed together loosely with jagged stitches crisscrossing the blood-clotted line of severance.”